Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowVIEWS & REVIEWS

HENRY BRINSLEY

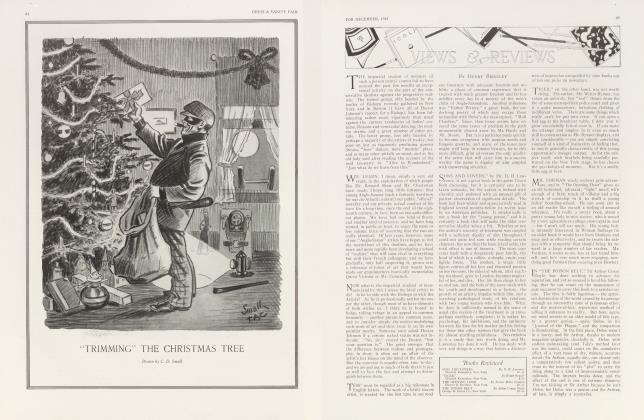

NOVELISTS may be roughly divided into two groups, mere story-tellers and "artist's'—an artist, in this case, being a story-teller with a style. (Thackeray, one remembers, was once described by a grudging critic as simply an average English clubman plus genius and a style!) Mr. Richard Pryce, whose "Jezebel" I have just been reading, belongs in the group of artists, as he certainly has a style, and a style of considerable merit sometimes approaching charm: but he for gets the old adage that art should conceal itself. Mr. Pryce's muse, in short, has a very obviously painted face. I haven't the least objection to painted faces,— I rather enjoy them when they are painted with delicacy and tact (Mr. Maurice Hewlett's muse has a miracle of a surface), and a lady at a costume ball is well nigh required thus to heighten her effectiveness. But a garden party is a different affair; here the obviousness of artifice should be reduced to a minimum.

AS a story, "Jezebel" will quite well repay reading. One accepts reluctantly the gross initial artifice of the heroine's name. It is difficult to grant that a gentleman however eccentric would thus burden an innocent child however firmly he may believe his wife to have chosen for her another father than himself; and Lord Dormoral's eccentricity through the rest of the book is not consistent with this initial brutality. After that, the book is a logical progression, despite the fantastic premiss. Jezebel grows up slowly and steadily, a beautiful and impulsive creature, the centre of a feud between two great county families (Mr. Pryce creates a society sufficiently aristocratic to satisfy the most exacting — and is jauntily at ease on Zion); Montague and Capulet march and countermarch, and finally Jezebel's name, after a momentary and fruitless attempt of hers to live up to it, becomes a badge of honor in subsequent editions of the local Debrett. In its nervous, acutely self-conscious, artificial way, the book is never dull. And if the love-making is done with a quivering sentimentality, I for one, admit a sneaking liking for sentimentality. The best part of the book is that which deals with Jezebel's childhood. That too, was the best part of "Christopher."

ON THE other hand, Miss Willa S. Cather in "O Pioneers!" (O title!!) is neither a skilled storyteller nor the least bit of an artist. And yet by the end of the book, something has happened in the reader's mind that leaves him grateful. The tale is one of a mixed community-of pioneer farmers, Swedes, Bohemians, French, and others, and focusses itself on a girl who when orphaned achieves success with her farm and her lover. There isn't a vestige of "style" as such: for page after page one is dazed at the ineptness of the medium and the triviality of the incidents. But at last, if one surrenders, there is a kind of cumulative effect — one feels that one has really lived in this simple community with the heroine, Alexandra, and shared her griefs, struggles, and satisfactions, which finally attain a dramatic interest. And the secret of this is the persistence throughout of a single fine quality of the author (a quality which Mr. Pryce's work seems to lack) — her extraordinary sincerity.

AFTER SO quiet an affair, Mr. E. F. Benson's "The Weaker Vessel" is a very vivid book. He bounds into the ring as an old friend of "Dodo" days, and at once turns a number of handsprings. The scene begins at a vicarage choir-rehearsal. "The organ had pale green pipes with an ecclesiastical design of otherwise unknown foliage stencilled on them, and contained a Vox Humana of peculiarly bleating tone, which sounded like a sheep that had very much gone astray." This is the good old authentic vintage of the '90's. The author quickly, however, becomes serious, as the theme amply demands seriousness. It is in skeleton, the brave struggle of the "weaker vessel," a vicar's daughter subsequently an actress, with the hidden vice of her husband, a meteorically successful playwright. The book is a brilliant study of drunkenness which I commend to every crapulous writer. Together with literary and artistic London we get a good deal of the country vicarage. . The Vicar's wife is a singularly diverting and maddening creature, with a touch of Mrs. Proudie and a recurrent trick of speech lifted bodily from our adored Mrs. Micawber. Indeed, the publisher's advertisements invite a comparison with Trollope; but it is Trollope and champagne, a little of the former and a great deal of the latter. Some people prefer to take these two separately; others, will relish a new mixed drink.

Books Mentioned:

JEZEBEL, By Richard Pryce

Houghton Mifflin Co., Boston and New York, 1913. $1.33 O PIONEERS! By Willa Sibert Cather

Houghton Mifflin Co., Boston and New York, 1913. $1-35

THE WEAKER VESSEL, By E. F. Benson

Dodd, Mead & Co., New York, 1913. $1.35

THE INSIDE OF THE CUP. By Winston Churchill

Macmillan Co., New York, 1913. $1-50

WINDS OF DOCTRINE, By George Santayana

Charles Scribner's Sons, New York, 1913. $1.75

RUNNING SANDS, By Reginald Wright Kaufman

Dodd, Mead & Co., New York, 1913. $1.35

ISOBEL, By James Oliver Curwood

Harper & Brothers. New York, 1913. $1.25

MR. WINSTON CHURCHILL gives us, with "The Inside of the Cup," a very strong, unmixed drink, with a small "love interest" thrown in as a lump of sugar. Since "Robert Elsmere" we have,not had so formidable a theological treatise in the guise of a novel. Every serious person is at times tempted to overhaul his religion, and scrutinizing the details with whatever earnestness he can summon, to discover what they really mean to him and how they square themselves with modern secular thought. The frequent result, with Roman Catholics, is what we call "Modernism." For Anglicans and thoughtful Protestants in general, Mr. Churchill offers the solution of his novel. It is impossible to discuss the problem in a brief review, but I commend anybody who, like Mr. Churchill, has been reading recent philosophical works which deal with religious thought, as do the later writings of William James and Professor Royce, the most brilliant book of essays of the year: "Winds of Doctrine," by George Santayana.

"THE Inside of the Cup" was bound to fall between two stools. If you take it up expecting a good novel, you may as well go hang; if you are interested in theological discussion the storytelling, as such, is an interruption. It has the defect of its qualities. The men and women alike in the book have an almost passionate interest in theological discussion — and each talks precisely like the other, with the same rhythm, inflection, style in short. Many of them are "characters" even less than the speakers in a Platonic Dialogue. But Mr. Churchill is so intensely in earnest, so filled with what Matthew Arnold desired — a high seriousness of purpose — that it is ungracious to characterize as a notably ineffective work of art a book that will so profoundly appeal to Chautauqua and the more thoughtful Broad-Church wing of his own Communion. Here again, the sincerity of the book will carry it far.

FOR a book devoid of any high seriousness of purpose, Mr. Reginald Wright Kauffman's "Running Sands" may be given the palm — and then the toe of the boot. One can imagine the tragedy of a man of fifty who honestly believes himself to be still essentially young, mated with a girl of eighteen, treated in a manner that might achieve both dignity and pathos. But when one uses such a subject as an opportunity for dull nastiness, and writes like a jaded drummer in a paper collar, there is little or no excuse. If a writer wishes to work in this genre, he should more carefully study de Maupassant and Zola, for the wit of the one and the apostolic zeal of the other: he will then be unwilling to stew in the fetid air of a third-class smoking compartment.

AFTER this, "Isobel," by James Oliver Curwood, comes like a fresh north wind. With any one who liked M r. London's early tales, or Sir Gilbert Parker's "Pierre and His People," this story will have a happy welcome. For it's a rattling good story as stories go nowadays, brisk and vivid. I once, years ago, asked Mr. Kipling how he happened to write "Quiquern." "Well you see," he said, "we've had a particularly severe winter in Vermont." But Mr. Curwood has obviously lived in the remote northwest and felt it all for himself. His style is far from distinguished, it lacks the poetic sweep of Mr. Kipling's and the crispness of Sir Gilbert's early touch, but it is a pleasant and adequate medium. The strongly emotional friendships of the men, however inarticulate, and the swift high passion of the men and women, however ineptly phrased, will to the reader on the deck of a yacht or in a garden chair sound almost painfully sentimental. To others who live in a rougher world, these passages will ring more nearly true, for they express things fundamentally noble and lovable with a fine disregard of self-consciousness. I should hesitate to call Mr. Curwood's novel at all important but to give the average reader a hearty and wholesome pleasure is in itself a fine achievement.

A WORD as to verse. To me the following if not the most important poem of the past few weeks is certainly the most engaging. It is by Mr. Joseph A. Torrey, and I quote it from the Boston Evening Transcript.

HORA VIRUMQUE CANO

There was a man, he had a clock, His name was Matthew Meats, Which he wound regular every night For almost twenty years.

At length his favorite timepiece proved An eight-day clock to be,

And a madder man than Mister Mears You would not wish to see.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now