Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

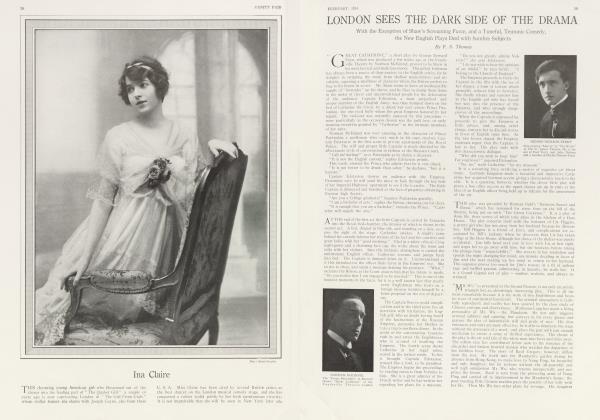

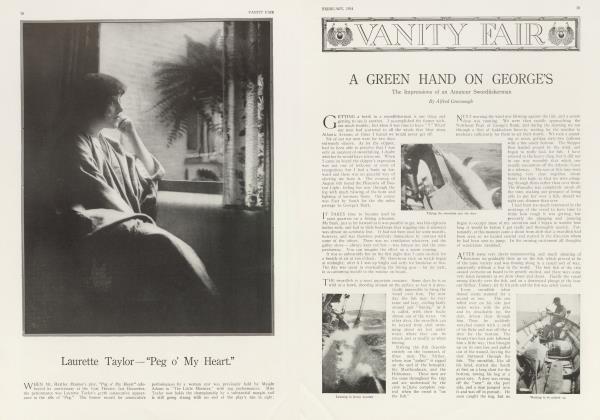

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowPLAYS WORTH WHILE

III—PRUNELLA

The Third of a Series of Articles Intended to Summarize and Interpret Critically the Twelve Best Productions of the Year

THIS is the third article in a series that embodies a new idea of monthly criticism. Each month, the writer of this department personally visits every legitimate play that is presented in New York: but, instead of devoting the space at his disposal to a summary review of all these presentations, good, bad, or indifferent, he concentrates on the one play which has appeared, from every point of view, to be the most important. In this way the maximum of space may be devoted to the study of good plays in a department that never concerns itself with inferior productions. In most cases, only one play will be reviewed each month: but whenever two or three plays of the first order of merit are produced within a week or two, this department will be extended, to include a study of them all. It is hoped that the department may ultimately serve as a standard guide to what is best in the current theatre.

IT IS interesting, at the present time, to reread the once celebrated preface that was written nearly twenty years ago by Maurice Maeterlinck to explain the designation of his early dream-dramas as " Plays for Marionettes." In this essay the Belgian poet said: "In truth, they were not written for ordinary actors. ...I believed sincerely, and I still believe to-day, that poems die when living beings are introduced into them." He then cited at length a well-known passage from that essay "On the Tragedies of Shakespeare" in which Charles Lamb had stated that "the plays of Shakespeare are less calculated for performance on a stage than those of almost any other dramatist whatever," because "there is so much in them which comes not under the province of acting, with which eye and tone and gesture have nothing to do." Enthusiastic theatre-goer though he was, Lamb was also a sedulous reader of Elizabethan plays, and he preferred the pleasure of the library to the pleasure of the gallery. We must make allowance for the personal equation in approaching his contention that any actual presentation of a tragedy must inevitably subtract from that impression of poetry which the reader of the text is able to imagine as he dreams at home beneath his lamp. But it was M. Maeterlinck's opinion twenty years ago that "Charles Lamb was right, and for a thousand reasons still more profound than those which he has given us. The theatre is the place where the majority of masterpieces die, because the representation of a masterpiece by the aid of elements that are accidental and human is a paradox."

IT IS evident, however, that M. Maeterlinck had changed his mind upon this point a dozen years later, when "The Blue Bird" was prepared for production at the Art Theatre of Moscow. In every scene of this poetic composition it is apparent that the author relied frankly on the harmonious collaboration of the designer of scenery and costumes, the stage-director, and (most of all) the electrician of the theatre, for the complete conveyance of his imagined and designed effect, and that it was only by means of all these marshalled media for visual suggestion that the author contrived to lure the spectator airily aloft to a region where he winged his way among invisibilities. "The Blue Bird," properly produced, is more poetic in the theatre than in the library; and it was designed to be so.

M. Maeterlinck's complete change of opinion in regard to the fitness of the actual theatre for conveying an impression of poetry must have been brought about by the very great advance which has been made, during the last twenty years, in the art of theatrical production. In a single generation the theatre has been changed from a place where masterpieces die to a place where plays that are potentially poetic are made to live indeed. Not only is our theatre rapidly ceasing to subtract from the poetry of such sublime works as the tragedies of Shakespeare, but it has already been improved to such a degree that it has become capable of adding to the poetry of compositions that rank a little lower than the highest. Many plays which scarcely seem poetic in the library become poetic in the theatre of to-day, after they have undergone transfiguration at the hands of an able stage-director.

MR. GORDON CRAIG has recently defined the drama as a compound art whose elements are "action, words, line, color, and rhythm." This definition designates five distinct media of expression, any of which may be employed to enforce poetical appeal. The literary element is only one of the five. It follows, in the case of a composition whose written text is scarcely poetic in itself, that the esthetic value of the play may be greatly enhanced in the theatre by a poetic handling of the other elements (action, line, color, and rhythm) by a stage-director who knows as much, and cares as much, about the theatre as Mr. Gordon Craig.

WE HAVE before us an interesting instance of a play which scarcely seems poetic in the library, but has been made to seem poetic in the theatre by a production of extraordinary beauty.

"Prunella: or, Love in a Dutch Garden" is a Pierrot-play in prose and rhyme by Laurence Housman and Granville Barker. The text of this little fantasy, which has been published in London by Sidgwick and Jackson, is disappointing and unsatisfying. It is so almost good (there seems to be no other phrase than that) that the reader feels discomforted because it is not better. "When you strike at a king, you must kill him," said Emerson to a young gentleman who had essayed to write an adverse criticism of Plato: similarly, when you attempt a fantasy in the mood of witty lyricism, you must conceive it with, the exuberant fancy and write it with the brilliant verbal preciosity of such an artist as Edmond Rostand. "Prunella" might have been perfectly composed by the same Rostand who wrote "Les Romanesques;" it might have been written very daintily and brightly by Mr. Austin Dobson; but the fancy of Mr. Barker and the verse of Mr. Housman seem a little too pedestrian for the occasion. Why, since this is so, have we been required to select "Prunella" as a Play Worth While?' It is because this composition has been lifted into poetry by the exquisitely beautiful stage-direction of Mr. Winthrop Ames. The visual rendering of "Prunella" by this admirable artist makes so perfect an appeal to the eye that the lines might almost be dispensed with, and the action projected in pantomime to the accompaniment of incidental music. It no longer matters, in the theatre, whether Mr. Housman's verse is good or bad — the attendant elements of action, line, color, and rhythm are all handled with such richness, of poetical appeal. But, properly to appreciate what Mr. Ames has. done for "Prunella," we must first examine the text in some detail.

ALL THREE acts are set in a picture-book garden wherein a prim little house is nested away from the world by high hedges of dipt yew. This is the residence of threePuritanical old maids, Prim, Privacy, and Prude. They had once had a younger sister, named Priscilla; but she had run away, into the alluring world beyond the hedges, with a landscape-architect who had come to erect a Pagan statue of Love within the garden. A year later, a little baby, named Prunella, had been consigned by the dying Priscilla to the care of the three aunts who lived immured behind the hedges.

Prunella has now reached the dangerous age of adolescence. She has been brought up very strictly; and she feels "that impulse to go strolling away, that longing after the mystery of the great world" which the gentle Hawthorne noted in one of the most charming of his youthful compositions. There is a company of mummers in the town. The garden is besieged with laughter and with music, and a shower of confetti is flung over the high hedges while Prunella is reciting her prudential lessons to her yawning aunts. Later, when Prunella is left alone in the garden, Pierrot creeps under the hedges and confronts her with an appealing pale face whose pallor he ascribes to unrequited love. The other mummers steal in and dazzle her with dancing and with laughter; and the cynic Scaramel experiences no difficulty in absconding from her the key to the high-hedged garden that is her prison-house.

At midnight, underneath the moon, the mummers return to the garden. Pierrot has brought along a hired tenor to serenade Prunella; and he prides himself upon this hired voice, in a brief passage that, for wit and fancy, is worthy of Rostand. Indeed, it seems to have been suggested by a well-remembered passage of the third act of "Cyrano." Prunella is wooed down from her window, and runs away with the mummers as her mother had run away before her. She becomes the Pierrette of that fantastic company, and fares forth, seeking Love, to discover Life.

When next we see the garden, three years later, it is overgrown, weedly and neglected. Prim and Prude are dead; and Privacy, after years of hopeless waiting for Prunella, has ultimately reconciled her mind to selling the little house to an unknown gentleman who wishes to possess it for sentimental reasons. The stranger is no other than Pierrot. He had deserted Prunella light-heartedly two years before; but a recrudescence of remorse had compelled him to return to the scene of the inception of their brief romance. It is a tattered and disenchanted company of mummers that he brings to sup with him in his penitential dwellingplace. These ghosts of a departed gladness are all gathered in the little house when the disconsolate Prunella wanders home to die. She sinks fainting at the feet of the Pagan statue of Love. But Pierrot discovers her; and his new impulsion of a love which, at last, is real and lasting, reawakens her to life. The two are finally united beneath a singing of the stars.

(Continued on page 80)

(Continued from page 31)

It will be noted that the essence of this narrative is merely the old, old story of seduction and disillusionment— a tale that has been told a thousand times and has been employed most effectively in the modern theatre in the "Sister Beatrice" of Maeterlinck. But the text of "Prunella" lacks utterly those intimations of immortality by which Maeterlinck reminds us that the oldest stories in the world are evermore the newest. These authors have elected to treat the subject lightly; but their muse is not gifted with the wings of fireflies. The lines are seldom witty enough, or pretty enough, to hit the mark of the occasion.

The writing is exceedingly uneven. It is best in the lyric passages— best of all, perhaps, in the following lovely stanzas:—

"Asleep on the edge of a town Where the high-road ran by, Stood a house with the blinds all drawn down,

As if waiting to die.

And everything there was so straight With high walls all about!

And a notice was up at the gate,

That told Love to keep out.

But Love cannot read— he is blind;

So he came there one day

And knocked; but the house was unkind,

It turned him away!

But lo, when the gates were all closed,

When the windows were fast,

At night while the householders dozed,

Love entered at last."

This little poem shows Mr. Housman at his best; but [unless we should blame Mr. Barker] he is also capable of execrable versification. Consider, for example, the following lines:—

"She come

Just a year afterwards, as small and young As they make 'em—found lying at the door Tied up in black ribbon, with a letter written By Miss Priscilla just before she died,

Saying the child was hers."

Charity withholds the critic from commenting on such passages as that.

But these literary inequalities are scarcely noticeable in the theatre. The lines are beautifully accompanied by incidental music composed by Joseph Moorat. There seems to be no other word for Mr. Moorat's music than the adjective "witty." It displays that same brilliant daintiness which we are accustomed to expect in the very finest vers de société. But the play has been helped even more by the visual appeal of the costumes and the scenery.

The costumes were designed by Mrs. O'Kane Conwell, and the scene was executed by Messrs. Unitt and Wickes; yet the guiding taste of Mr. Ames is evident in both. In the first act, there is a little note of pale blue that is repeated from costume to costume and sings its way all around the stage before a background of deep green. It is difficult to record in words such delicate effects as this; yet these little matters constitute the poetry of color. When the mummers romp about the stage, it is as if a dozen little laughing lyrics by Herrick and Carew had come alive, as children say, and changed their words to dances. Such loveliness of sheer design has never been seen before upon the American Stage.

Far up in the centre of the scene, there is a great gate between the hedges; and the view through this gate repays, alone, a visit to the theatre. We gaze with Prunella through this gate as a caged bird peers through its bars. We look for miles and miles and miles. Wan water is lying low amid mysterious hills, that lure us onward, ever onward, to an unattainable horizon. And over this pale water, clouds are floating, that gradually change their forms and tints with the changing hours of the day and night. Here, at last, upon the stage has been depicted an air that we can actually breathe.

It is even more difficult to suggest the poetry of lighting which Mr. Ames has evidenced in this production. Mr. Belasco lights his stage so well that the public perceives and admires his artistry; but Mr. Ames has lighted his stage so much better that his artistry is imperceptible and scarcely any one admires it. But it would be worth the while of any spectator who really cares about the artistry of theatrical production to watch the subtle play of light on the clouds in the distant sky, and to wonder at the perfect quality of the moonlight which drenches "the greenly silent and cool-growing" garden throughout the second act.

Here, then, we have a poetical production of appealing beauty accorded to a piece that, in itself, could scarcely be called worth while. Mr. Ames has afforded us an emphatic instance of the extent to which the modern theatre may be made to increase the poetry of compositions that rank a little lower than the highest.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now