Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

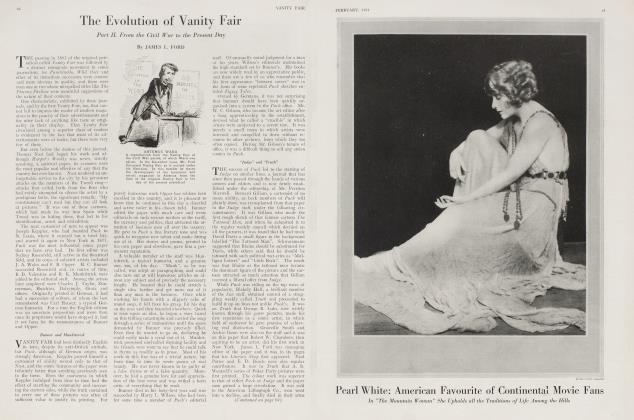

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowGEORGE ARLISS, PORTRAYER OF STAGE GENTLEMEN

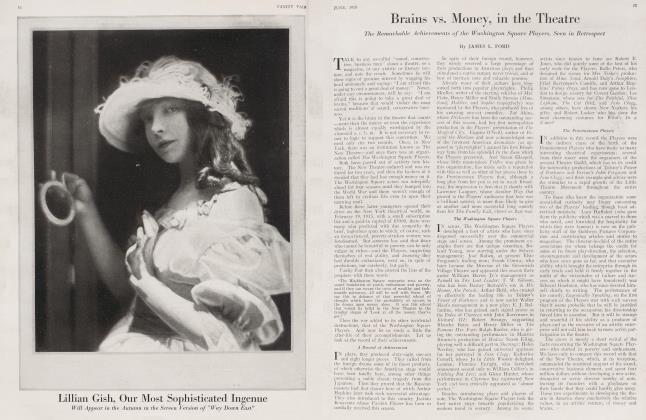

MR. GEORGE ARLISS is able to play a gentleman on the stage not merely because he is well bred himself—as he unquestionably is—but because he is an artist.

The actor who wishes to receive the credit due him as an artist by playing the part of a gentleman must defy the superstition that "it takes a gentleman to play a gentleman." No one would assert that it takes a real blacksmith to play the "Maitre de Forge," or that only a celibate can impersonate a priest. Why then is the role of a gentleman considered beyond the grasp of any actor who is not himself of patrician birth? As a matter of fact, it takes an actor to play a blacksmith, or a clergyman, or a thief, or a beggar, or a gentleman, and among them all there is none less complex than this last, who is simply a man who has never acquired any vulgar tricks; one who, at his highest, loves his neighbor as himself.

It was in the role of a titled aristocrat in Mrs. Pat Campbell's company that Mr. Arliss was first seen in this country. He was so good in this modern light comedy part that Belasco hastened to engage him for the tragic role of the War Minister in "The Darling of the Gods," and it was in this that he made his first deep impression on American theatregoers. It was a finished portrayal of the malevolence of a high-bred gentleman, graceful, distinguished, and thoroughly oriental.

We next saw him in Mrs. Fiske's company, playing Lord Steyne, one of the greatest aristocrats in English fiction, a gentleman and a villain still—one who loved at least one of his neighbors, to his own and her undoing. The position was one of many difficulties. The character as drawn by Thackeray was so sharply defined that every reader of the novel had sharply visualized it and expected to see on the stage precisely what he had long seen so clearly in his mind's eye. In a previous production the part had been acceptably played by another actor, and it was therefore incumbent on his successor to give an entirely different but equally forceful rendition. Moreover the character was unsympathetic and at the same time a gentleman—and "it takes a gentleman to play a gentleman." That Mr. Arliss overcame these difficulties and gave a performance that added materially to his renown is now a matter of dramatic history. His Lord Steyne lingers in my memory as a man who was many things besides a gentleman and a villain. To me he was the living embodiment of Thackeray's creation.

Another well-bred but unsympathetic part that Mr. Arliss impersonated was that of the degenerate Frenchman in "Leah Kleschna." Next we saw Arliss as the Devil. I recall it as an artificial role in an artificial play, performed as such a role should be, but not adding much to the actor's reputation. By this time, however, he had built up a following of his own that would accept him in almost anything, and with these his D evil easily passed muster as a performance of unusual subtlety. His Septimus was, to me, the least satisfying of his creations, though that was not altogether the fault of the actor.

That Mr. Arliss is best known to theatregoers as the impersonator of Benjamin Disraeli is not to be deni ed. The play is not generally regarded as worthy of his talents, and it is certainly weak in that the title rôle has no strong part opposing it. Moreover when the drama was first presented the American public knew very little about the hero, so that Mr. Arliss's tours may be said to have had a certain educational value. But those who were familiar with Disraeli's career felt something like a thrill when the player made his first entrance, looking as if he had just stepped out of a Tenniel cartoon.

His Disraeli has given complete stability to his vogue. In his next play, Mr. Arliss will find his audiences waiting for him.

James L. Ford

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now