Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowSENSATIONS OF A CITY

Arthur Symons

In Praise of the Ballet

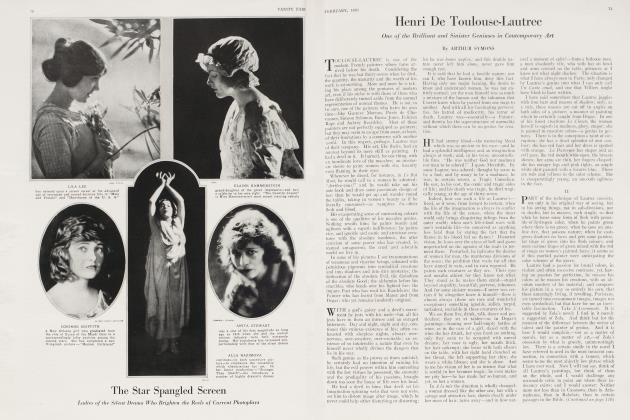

I HAVE always found a peculiar interest in what is artificial, properly artificial, in London. A city is no part of nature, and one may choose among the many ways in which something peculiar to walls and roofs and artificial lighting is carried on. All commerce and all industries have their share in taking us further from nature and further from our needs as they create about us unnatural, conditions which are really what develop in us these new, extravagant, really needless needs. And the whole night-world of the stage is, in its way, a part of the very soul of cities. That lighted gulf, before which the footlights are the flaming stars between world and world, shows the city the passions and the beauty which the soul of man in cities is occupied in weeding out of its own fruitful and prepared soil.

That is, the theatres are there to do so, they have no reason for existence if they do not do so; but for the most part they do not do so. The English theatre with its unreal realism and its unimaginative pretences towards poetry left me untouched and unconvinced. I found the beauty, the poetry, that I wanted only in two theatres that were not looked upon as theatres, the Alhambra and the Empire. The ballet seemed to me the subtlest of the visible arts, and dancing a more significant speech than words. I could almost have said seriously, as Verlaine once said in jest, coming away from the Alhambra: "J'aime Shakespeare, mais . . . j'aime mieux le ballet!" Why is it that one can see a ballet fifty times, always with the same sense of pleasure, while the most absorbing play becomes a little tedious after the third time of seeing? For one thing, because the difference between seeing a play and seeing a ballet is just the difference between reading a book and looking at a picture. One returns to a picture as one returns to nature, for a delight which, being purely of the senses, never tires, never distresses, never varies. To read a book even for the first time, requires a certain effort. The book must indeed be exceptional that can be read three or four times, and no book was ever written that could be read three or four times in succession. A ballet is simply a picture in movement. It is a picture where the imitation of nature is given by nature itself; where the figures of the composition are real, and yet, by a very paradox of travesty, have a delightful, deliberate air of unreality. It is a picture where the colors change, re-combine before one's eyes; where the outlines melt into one another, emerge, and are again lost, in the kaleidoscopic movement of the dance. Here we need tease ourselves with no philosophies, need endeavor to read none of the riddles of existence; may indeed give thanks to be spared for one hour the imbecility of human speech. After the tedium of the theatre, where we are called on to interest ourselves in the improbable fortunes of uninteresting people, how welcome is the relief of a spectacle which professes to be no more than merely beautiful; which gives us, in accomplished dancing, the most beautiful human sight; which provides, in short, the one escape into fairy-land which is permitted by that tyanny of the real which is the worst tyranny of modern life.

The most magical glimpse I ever caught of a ballet was from the road in front—from the other side of the road—one night when two doors were suddenly thrown open as I was passing. In the moment's interval before the doors closed again, I saw, in that odd, unexpected way, over the heads of the audience, far off in a sort of blue mist, the whole stage, its brilliant crowd drawn up in the last pose, just as the curtain was beginning to go down. It stamped itself in my brain, an impression caught just at the perfect moment, by some rare felicity of chance. But that is not an impression that can be repeated. For the most part I like to see my illusions clearly, recognizing them as illusions, and so heightening their charm. I liked to see a ballet from the wings, a spectator, but in the midst of the magic. To see a ballet from the wings is to lose all sense of proportion, all knowledge of the piece as a whole, but, in return, it is fruitful in happy accidents, in momentary points of view, in chance felicities of light and shade and movement. It is almost to be in the performance oneself, and yet passive, with the leisure to look about one. You see the reverse of the picture: the girls at the back lounging against the set scenes; turning to talk with someone at the side; you see how lazily some of them are moving, and how mechanical and irregular are the motions that flow into rhythm when seen from the front. Now one is in the centre of a joking crowd, hurrying from the dressing-rooms to the stage; now the same crowd returns, charging at full speed between the scenery, everyone trying to reach the dressing-room stairs first. And there is the constant traveling of scenery, from which one has a series of escapes, as it bears down unexpectedly in some new direction. The ballet half seen in the centre of the stage, seen in sections, has, in the glimpses that can be caught of it, a contradictory appearance of mere nature and of absolute unreality. And beyond the footlights, on the other side of the orchestra, one can see the boxes near the stalls, the men standing by the bar, an angle cut sharply off from the stalls, with the light full on the faces, the intent eyes, the gray smoke curling up from the cigarettes: a Degas, in short.

And there is a charm, which I cannot think wholly imaginary or factitious, in that form of illusion which is known as make-up. To a plain face, it is true, make-up only intensifies plainness; for make-up does but give color and piquancy to what is already in a face, it adds nothing new. But to a face already charming, how becoming all this is, what a new kind of exciting savor it gives to that real charm! It has, to the remnant of Puritan conscience or consciousness that is the heritage of us all, a certain sense of dangerous wickedness, the delight of forbidden fruit. The very phrase, "painted women," has come to have an association of sin, and to have put paint on her cheeks, though for the innocent necessities of her profession, gives to a woman a kind of symbolic corruption. At once she seems to typify the sorceries and entanglements of what is most deliberately enticing in her sex:

"Femina dulcc malum, pariter favus atquc venenum—"

with all that is most subtle, least like nature, in her power to charm. Maquillage, to be attractive, must of course be unnecessary. As a disguise for age or misfortune, it has no interest. But, of all places, on the stage; and, of all people, on the cheeks of young people; there, it seems to me that make-up is intensely fascinating, and its recognition is of the essence of my delight in a stage performance. I do not for a moment want really to believe in what I see before me; to believe that those wigs are hair, that grease-paint a blush; any more than I want really to believe that the actor who has just crossed the stage in his everyday clothes has turned into an actual King when he puts on clothes that look like a King's clothes. I know that a delightful imposition is being practiced upon me; that I am to see fairy-land for a while; and to me all that glitters shall be gold.

THE ballet in particular, but also the whole surprising life of the music halls, took hold of me with the charm of what was least real among the pompous and distressing unrealities of a great city. And some form I suppose of that instinct which has created the gladiatorial shows and the bull-fight made me fascinated by the faultless and fatal art of the acrobat, who sets his life in the wager, and wins the wager by sheer skill, a triumph of fine shades. That love of fine shades took me angrily past the spoken vulgarities of most music-hall singing (how much more priceless do they make the silence of dancing) to that one great art of fine shades, made up out of speech just lifted into song, which was so well revealed to us by Yvette Guilbert.

It was out of mere idle curiosity that I had found my way into that world, into that mirror, but, once there, the thing became material for me. I tried to do in verse something of what Degas had done in painting. I was conscious of transgressing no law of art in taking that scarcely touched material for new uses. Here, at least, was a décor which appealed to me, and which seemed to me full of strangeness, beauty, and significance. I still think that there is a poetry in this world of illusion, not less genuine of its kind than that more easily apprehended poetry of a world, so little more real, that poets have turned to.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now