Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowTHE JOCKEY CLUB'S BREEDING BUREAU

F. K. Sturgis

Chairman of the Breeding Bureau of the Jockey Club

Part I

EDITOR'S Note:—The wide demand for horses in this country by the Powers at war has proved the economic value of the thoroughbred horse and the importance of the work of the Jockey Club's breeding bureau.

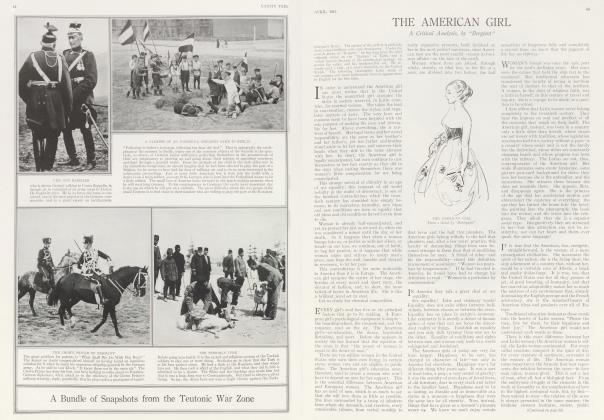

THE agents of England, France and Italy are going over this country with infinite care, in search of horses suitable for service on the battlefields of Europe. England and France have a fleet of specially furnished horse transports, which make fairly regular schedules between American and Canadian, and French and British ports. They are equipped to take away, without requisitioning tramp help, from 50,000 to 60,000 horses a month. Two or three times a week, shiploads of from 800 to 1,500 animals leave the United States through Gulf and Atlantic ports and by way of Canada.

According to the reports of the Bureau of Animal Industry at Washington, as many as 200,000 horses had been shipped out of the country up to the first of February. The Superintendent of Animal Husbandry in Pennsylvania gives the figure as even larger. He declares, in an appeal for State help to encourage farmers to make good the country's losses in horseflesh, that our exportations have reached the total of 500,000. Whether this is an exaggeration or not, the traffic is steadily increasing in volume, because the United States is the only country which has horses to spare. If the war continues another year, as Lord Kitchener predicts, we shall have sold upwards of a million horses to the warring powers.

OFFICERS of the British and French armies estimate that 5,000 horses are rendered totally unfit for service every day, by wounds, poor feeding and disease. This rate of destruction is increasing, because the animals that escape death under fire are being killed more and more rapidly by the increasing overwork. It is an impossibility now to put back more than one horse for every two killed, and in a few months hence the armies in France will be fortunate if they get one for three.

No country is escaping the general proscription of horses now under way. Canada was

combed clean long ago; and agents of the allied powers are as busy in the Argentine, Australia, New Zealand, India and South Africa as they are in the United States. German and Austrian buyers would be just as active if the British command of the sea did not preclude the shipment of contraband of war into their countries.

When peace is proclaimed and the military staffs of the belligerent nations begin their work of reorganization, the accumulated demand for horseflesh will be tremendous. It is possible to gather some idea of what they will need, from an estimate which Sir John French made last'winter of the mobilization requirements of the major powers at that time. He declared that the British army then required 153,000 horses for effective mobilization; Canada, 82,000; and Australia and New Zealand, 55,000. In his opinion France needed 40,000; Germany, 50,000. The need of Russia was a secret of the St. Petersburg war office; but inasmuch as Russian agents had not been active in foreign markets, it was assumed that Russia had a sufficient supply. Austria-Hungary was the only European country which had enough horses for her military needs at the beginning of the present war.

The great military need for horses cannot be evaded. Useful as the motor truck has proven to be for transporting soldiers, artillery and supplies over good roads in fair weather, its efficiency all but vanishes when the winter storms make quagmires of the unmacadamized roads; and the automobile has not been invented which is suitable for the cross country work that falls to cavalry and light artillery.

FRANCE, thirty years ago, took over the control of horse-racing as a military proposition and began systematically to encourage the farmers to breed all classes of thoroughbred grades. Germany followed the lead of France with respect to managing racing and encouraging breeding, and, in addition to home-produced stock, reinforced her armies by importations from Great Britain and Ireland, the United States, Argentina, and even from France; Russia has the Imperial studs of Lithuania and Poland and the breeding stations of Southern Russia. Austria-Hungary has been systematically breeding thoroughbred grades since the close of the Napoleonic Wars, and her remount stables were well stocked at the beginning of the great war last August. Her cavalry was the best mounted of any of the powers at war.

THE horses that European buyers are shipping abroad are animals of no particular breed, but such as one sees every day on the country roads of New England. It is not because these ordinary horses are the most serviceable, but because the bettei types thoroughbreds and thoroughbred grades—are not now obtainable. The ordinary horse is good enough for farm and road uses, but it lacks the bottom, courage and endurance which make the thoroughbred and the thoroughbred grades ideal military horses. Nevertheless, foreign buyers have to take these ordinary horses and to pay from $200 to $300 a head for them, according to quality.

They are obtained almost exclusively in the Middle-Western, Southern and Prairie states. The farmers of New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Maryland and Virginia have few common animals to spare from faun work. They are chiefly breeders of the highly specialized horse, for which the military powers are willing to pay from $400 to $600. Their breeding, however, was seriously restricted by the legislation which closed the race courses of New York in 1911 and 1912 and made the revival of racing difficult and expensive in 1913 and 1914. Their present inability to furnish military grades is a proof of the economic mistake of the attack on racing intended to prevent betting, but resulting in the partial destruction of the breeding industry.

TN 1906, the Jockey Club of New York adopted a scheme proposed by H. K. Knapp, to establish and maintain a public breeding bureau in New York State. The object was to prove the value of the thoroughbred blood, and to demonstrate the ability of the thoroughbred stallions to get the type of horse in greatest military demand.

Stallions of the best thoroughbred blood were selected with special reference to their fitness in the attributes of temper, intelligence, conformation and physical soundness; and were placed at stations convenient to all sections, and advertised for service at nominal fees. The idea took quick hold: the reports of the Jockey Club show that 1,083 mares were bred to bureau stallions in 1907; and 1,058 in 1908 (and these records are incomplete). Had conditions continued favorable to racing since the establishment of the bureau, the offspring of these thoroughbred stallions and cold-blooded mares, in New York today, would number 6,500 or 7,000 thoroughbred grades, having a market value, at the conservative estimate of S400 a head, of between $2,600,000 and $2,800,000.

The agitation against racing, however, exerted a depressing effect. It became impossible for the founders of the bureau to maintain the enterprise on the scale at first intended; or to expand it—until 150 or more stallions had been placed at service; or to found a stud book for the proper registration of bureau foals. Bureau stallions died naturally, or were destroyed because of the development of diseases which rendered them unfit for further service; and these losses could not be replaced.

In the seven lean years which have elapsed since the first of the laws antagonistic to racing were written into the statute books at Albany, thoroughbreds to the value of five or six millions of dollars have been shipped from American ports to the welcoming markets of Germany, Austria, Hungary, Italy, Russia, France, Japan, the Argentine Republic, and Australia. The production of grades has been characterized, except in 1910, by a gradual reduction from season to season: only 410 livng foals were reported in 1909; 438, in 1910; 366, in 1911; 282, in 1912; 253, in 1913; and 200, in 1914.

AMONG the great thoroughbred stallions which America lost in this migration were Ethelbert, holder of the American record of 3:49 1-5 for two miles and a quarter, and his famous sons Fitz Herbert and Dalmatian. Also Adam, who had been brought from France in 1907 at a cost of $65,000; Rock Sand, purchased by August Belmont for $125,000, in England, in 1906; Sir Martin, purchased by Louis Winans, an English sportsman, for $75,000, in 1908; Kinley Mack, winner of the Brooklyn and Suburban Handicaps of 1900; Meddler who twice sold for $75,000; Voter, a famous sprinter and the sire of the great horse Ballot; not to mention Africander, Reliable, McChesney, Gerolstein, Adam Bede, Planudes, Bassetlaw, Ypsilanti, First Water, Novelty and Edward. In addition to these stallions, four or five thousand equally valuable broodmares were lost.

(Continued on page 88)

(Continued from page 37)

A syndicate of English, French and American breeders paid Mr. Belmont $150.000 for Rock Sand and established him in France. The worth of RockSand as a breed improver and the loss which the thoroughbred industry suffered by his withdrawal are indicated by the valuation Mr. Belmont placed eighteen months ago on Tracery, one of his sons. When Tracery finished his racing career in England in the autumn of 1913, after beating the stars of the British turf, Mr. Belmont refused an offer of $200,000 for him, made by Lady Douglas, in England.

An agent of the Hungarian war office paid $58,000 for Adam when that son of Flying Fox was offered at public auction in Paris in 1910, after two stud seasons in this country. The great Hermis became the property of the French government, and is breeding remounts in France. Fitz Herbert is privately owned in France. Novelty is in Brazil. Kinley Mack, McChesney, First Water, Reliable, Africander, and Gerolstein, are in the Argentine Republic; and Planudes is in Australia. Since 1908 the owners of the greatest American breeding establishments have annually shipped their best yearlings abroad for racing and the sales ring; and none of them come back.

Sportsmen in New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Maryland and Virginia, and in Kentucky and Tennessee, as well, had followed, or had planned to follow the example of New York and to encourage the breeding of military grades by bureau work in connection with racing. But, their work had to be abandoned. Without the aid of the thoroughbred market of New York to maintain a high standard of value which would keep the thoroughbred stallions and mares in the United States, they were unable to secure the necessary stock horses.

In Canada, on the other hand, the history of breeding has been quite different. The National Breeding Bureau, patterned after the New York Bureau model, was established in 1908 by the enterprise of John F. Ryan of Montreal. It has received government aid, and is now a flourishing concern. The Canadian government recognized the economic value of the thoroughbred and halfbred horse, and the agency which racing performs in his production; and refused to interfere with racing in 1909 and 1910.

THE work of the Canadian Breeding Bureau has expanded to the limits of the Dominion. With Sir John French, and Major J. W. Stephens, of Montreal, in its directorate, it has, indeed, become part of the British Empire's system of defense. It has, scattered through the provinces of the Dominion from Halifax to British Columbia, between 85 and 90 stallions—nearly all of them United States bred, the voluntary gifts of horsemen from this side of the border who have raced in Canada during the last five or six years. As has been the case with the breeding bureau of New York, the Canadian institution has been called upon to expend but little money for the purchase of stallions.

Canadian farmers will secure a handsome profit in furnishing th? British army with grades for the impending reorganization; but their supply will fall far short of the demand. If racing had been let alone in the United States the farmers of New York, and of the neighboring breeding states of New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Maryland and Virginia, as well, would now be in a position to help out, to their pecuniary advantage. As it is, they have no grades to sell and it is now being brought home to them that the legislative attack on racing in New York State in 1908 and 1910, during the two administrations of Charles E. Hughes as Governor, was a great economic mistake.

It is improbable that there are more than 2,700 halfbreds by New York stallions alive; and these arc mostly in the hands of wealthy followers of hunting in New York and New England, who use them for cross-country work, and who are not concerned by the mobilization needs of Europe. The New York Bureau organization is intact, however, and the officers of the Bureau stand ready to expand to meet any demand that may be made upon the farmers for military horses, provided there is sufficient improvement in the condition of racing in the next few years to enable them to do so.

THE condition is worth considering. Few of the items of commerce thrown our way as a result of the industrial and agricultural paralysis of Europe since August, have brought more substantial returns than the trade in horseflesh. Upwards of forty millions of dollars have come to American farmers and breeders in six months, in exchange for horses. England, in half a year, has spent half as much for American horses as she spent with us during the whole course of the Boer War. France has been nearly as lavish a buyer, though she was better equipped at the beginning of the war than her ally, in the matter of cavalry and artillery remounts, and transport animals. Italy, not yet at war, has given New York firms two orders for 25,000 each, in two months. This is a traffic which merits in its every phase, the serious attention of economists.

(To be concluded in the May issue of Vanity Fair.)

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now