Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowTH' AVENUE

Observations on Women, Noses, Fur Boas, and Side-laced Boots

Charles Macomb Flandrau

ALIGHT-COLORED, glittering afternoon but hot and humid as it so often is in cities near the sea. Strolling men rempve their hats from time to time and mop their faces—that is to say, the carefully and well dressed men dab lightly with fresh handkerchiefs at their eyes and foreheads, seeking to give the gesture an air of unconscious dignity, while other men with soiled handkerchiefs frankly swab. The women, however, neither swab nor dab and for blocks and blocks I speculate as to the means by which they have achieved this interesting—this marvellous impermeability. Their cool-looking, agreeably artificial epidermises convey the impression of being absolutely guaranteed not to run. They must do something for it of course, because they are always doing something. Last year they spent most of their time in japalacking their noses a glacial white and they did it everywhere — at the theatre, at the dinner table, in auto-busses, and on street corners.

I shall always remember 1914 not as the year in which the worldwar broke out, but as the year in which every one of thirty million American women simultaneously developed and wore for months, a dead looking, snowlike, whited sepulchre of respiration. They did not in the least resemble noses. It was more as if some very morbid person had held up every woman he met and, more or less in the middle of her face, had permanently affixed a marshmallow. And then suddenly, overnight almost, like a flock of timid cockatoos all these facial ice-cream cones disappeared, leaving mankind to wonder which was the more amazing—the unexpectedness of their mobilization, or the magic of their retreat. As Francois Villon, in his wistful fashion once inquired: "Mais où sont les nez d'antan?"

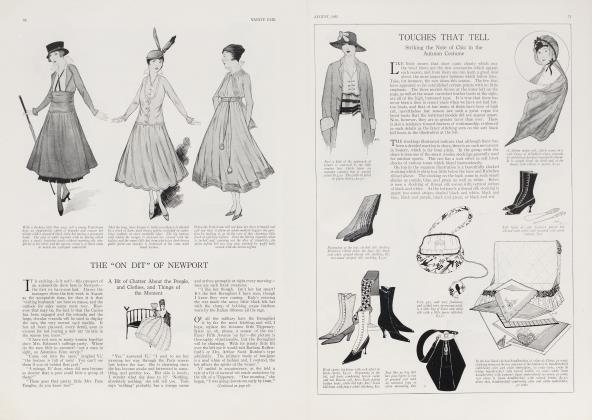

THIS afternoon, on the other hand, I have become aware that hundreds—no, thousands —of women, in spite of the summer's heat, are wearing about their necks a broad, fluffy strip of fur bleached to a soiled white. On one end of it usually dangles the head of some animal I have as yet not encountered in my excursions into zoology. How did it happen? Who suggested it? Why do they do it? It must be extremely uncomfortable on a day like this. And who are all these ladies anyhow? For it is a curious fact that never by any chance does one meet a woman of one's acquaintance garotted in a strip of soiled white fur. They appear to be a sect, a sisterhood apart whose walk in life I am quite unable to determine, for although one would hesitate to say that intellect and refinement were their most salient traits, most of them appear to be entirely what is called "respectable." They trip along, some of them pretty, some of them commonplace and some of them grotesque, but they all display this badge of a mental or social affinity whose secret I am so unable to solve.

But then in men also, I reflect, there is something of this tendency to adopt the conspicuous, the superfluous, the identical, and I thereupon begin to count the men who have recently discarded their eye-glasses and appeared in circular goggles bordered by black

horn or tortoise shell, clinging to their ears on thick and startling hooks. For to a certain type of man (why, I do not know, except that he is a certain type of man.) it all at once became obligatory to look like a cross between a beetle and a diving-bell, and there are so many of him on the avenue that I soon cease to count. However, "No hay reglas fijas," as they say in Spanish speaking countries when you ask for information on any subject. If men sometimes display this passion for newness in uniformity, women go much further in their passion for newness in multiplicity.

"Look upward, not downward," we have been admonished, but who in this epidemic of chromatic shoes is going to look for long at a time at the monotonous sky? Once—ages ago—so long that scarcely anyone remembers it (about three months I think it was), shoes differed in size and in state of preservation, but their colors were black or tan and women kept them on by lacing them up the front or buttoning them up the side. That was all; there was nothing more to it; the imagination went no further. Today women do not wear shoes at all; their feet are incased in cubist landscapes, in futurist music—in vers libres, and as no one has ever been able satisfactorily to describe such things I cannot

bring myself to court another failure. It is enough to say that with eyes downcast below the line where skirt and boot-top meet it is impossible nowadays to determine whether a woman is walking ahead of you, coming toward you, skidding to one side, or endeavoring to climb up in the air. All the old points of the pedal compass have been multiplied, interchanged or entirely abandoned. There is nothing to steer by and one speculates on whether or not the wearers know where they are going themselves. They probably don't. Signs of the times—signs of the times!

THEN, in a twinkling, the avenue for some reason is no longer a matter of individual faces, occasional extraordinary frocks, or detached objects of beauty and value in certain windows. It has once again become the terrifically magnificent, and brilliant, and interminable spectacle as a whole that at certain hours it really is. Does anyone ever become entirely accustomed to it and unaware of it? I doubt that, although certain gentlemen returning in automobiles from their downtown labors endeavor, by enveloping their heads in the evening papers, to give the impression that they long since have.

COMPLETE insensibility to this continuous double line of all too rapidly gliding motors—an appalling cinametograph of the entire human race—to the unidentifiable myriads swarming along the sidewalks, swarming—as if the hive had been opened or the hill disturbed—for miles; to the other swarms, who swarm transversely so to speak, when the policeman extends his arm and holds up his white-gloved hand; to by no means the least wonder of it all—the policemen themselves; to the unimaginable impression one constantly receives (almost like a physical impact) of untold energy and wealth and luxury and idleness and color and drabness and ugliness and beauty, all seething like some senseless, undirected torrent let loose in a gulch—complete insensibility to this, I should not be able to understand. How impossible to judge of Fifth Avenue, once you are a part of it. How merged one's mind becomes in it.

SO, then, after carefully calculating how I may get the greatest possible effect from it all, for the least possible money, I abruptly hop on a passing motor-bus and am lurched upstairs to a (comparatively) front seat.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now