Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

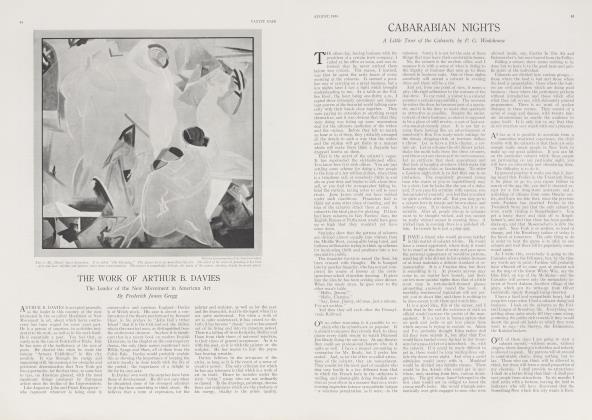

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowTHE WORK OF ARTHUR B. DAVIES

The Leader of the New Movement in American Art

Frederick James Gregg

ARTHUR B. DAVIES is accepted generally as the leader in this country of the men interested in the so-called Modernist or New Movement in art, about which fierce controversy has been waged for some years past. He is a person of surprises, in activities incidental to his work, as well as in his work itself. He is essentially a poet. You feel that, as surely as in the case of Botticelli or Blake. But he has none of the inefficiency of the race of poets. He showed this when he made the famous "Armory Exhibition" in this city possible. It was through his energy and organizing skill, his contempt for obstacles and persistent determination that New York got the opportunity, for the first time, to come face to face, on American ground, with the most significant things produced by European artists since the decline of the Impressionists.

Like Augustus John and Frank Brangwyn— who represent whatever is being done in conservative and cautious England—Davies is of Welsh stock. His case is almost a confirmation of the theory put forward by Bernard Shaw, in his preface to "John Bull's Other Island" that it is the Celt and not the Briton who is the practical man, as distinguished from the sentimental dreamer. Anyhow it is significant that in a recent book on modern English Literature, in the chapter on the contemporary drama, the only three names mentioned were Wilde, Synge and Shaw, all of them from the Celtic Pale. Davies would probably explain this as showing the importance of keeping the artistic faculty in close touch with the life of the period; the importance of a delight in life for its own sake.

In Davies' own work the surprises have been those of development. He did not care when he disquieted some of his strongest admirers by giving them something to think about. He believes that a form of expression, for the painter and sculptor, as well as for the poet and the dramatist, is at its strongest when it is not quite understood. For when a work of art is quite understood, it has ceased to disturb; it has become " classic" and so has passed out of its living and into its museum period. There is a falling off from Euripides, Shelley and Ibsen from their times of universal rejection, to their times of general acceptance. As it is with the poet, so it is with the painter or the sculptor. He has reason to fear the populace bearing wreaths.

Davies believes in the arrogance of the artist, as long as it is the result of a sense of creative power. The only criticism for which he has any tolerance is that which is a work of art in itself. Hence he includes under the term "artist," many who are not ordinarily so classed. In the drawings, paintings, decorations and sculptures which are the products of his energy, vitality is the prime quality.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now