Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowRemoving the Motes from Motors

GEORGE S. CHAPPELL

A Bill to Standardize the Social Side of Automobiling

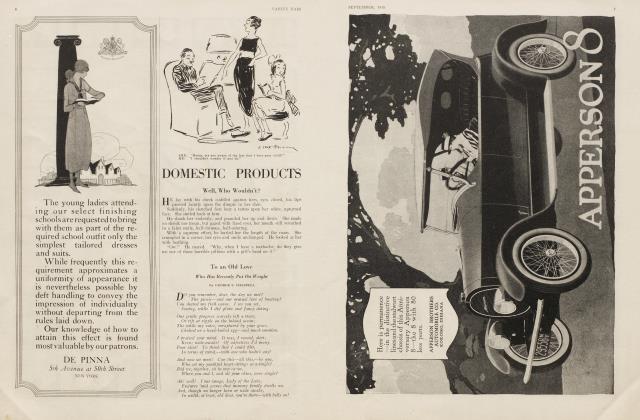

THE matter of motors is the main motif of modern man. My! what a perfectly lovely sentence to begin with! And it's so true, too,—most of us, most of the time, are either in or under a machine of some sort. The control and regulation of automobiles to-day touches every man,—or comes so near touching him that he has almost cause for a law-suit.

Why, then, not run the whole subject properly? Instead of going on in our aimless American way, letting things take care of themselves, why not be scientific, appoint a commission and pass a bill?

And, with all modesty, may I say that when it comes to selecting a father for the bill, I am the Boy? Besides having given the matter a lot of thought, I also have real political instinct. I am a student of conditions and I know how to spend money—judiciously, of course.

Naturally, the bill which I have in mind would embody the feature of government control. That is positively the last word in Washington style, and any measure which does not have the government control tassel on it is as hopelessly out of date as my cousin Egbert, who recently went to a tennis match wearing a sash with pockets. The government has its finger in most of the great mysteries of life,—birth, food-supply, railroads, any number of things— so why not in this burning question of automobiles?

IT is the most vital thing I can think of at the present time, and I've looked into a good many little matters in my time. For instance, there was that trouble we had with the boll-weevil. I was all mixed up in that. It wasn't until my Aunt Hannah had contributed three hundred dollars to the cause (through me) that I discovered that the poor old lady, confused by alliteration, thought she had been combating the social evil, whatever that is. When I explained to her that the bollweevil was an insect, she looked more horrified than ever and said, "Imagine giving it to young girls!"

Weather-control was the next vital matter that claimed my attention. There's a subject for you! There's a life work! It has been very sloppily handled, up to date, and I am sure a lot of money could be spent in that direction.

And then, suddenly,—about two months ago, to be exact,—the proper regulation of automobiles loomed up in my cosmos as the one big, crying need of the hour. Never having had a car before, I suppose I was careless and casual about the matter. It's curious how little a puncture or a blow-out means when you are only a passenger. You know how it is— you merely light a long cigar and wonder if you will have to get out while they jack up the axle. But when you become an owner,—well, it's a new world entirely. You even speak a new language. For instance, only two nights ago I was dining with my friends, the Paddlefords,—they are really charming people, just recently bitten by the motor bug. We had run out to Stagger Inn, in their little dollar car, and I asked Mrs. Paddleford about her mother's health,—not that it really mattered, but the cocktails were slow in coming and one must say something.

"Well," she said, with a sigh, "I've been quite worried lately about Mother. She has developed a knock in her engine,—she has never been quite the same since her fall last Spring. You know, she went about on a flat tire for nearly four months."

How expressive! How graphic! Can't you just see Mother's condition? And there you are. Even in the carefree moments of social intercourse, you can't get away from the motor; it's the one great overwhelming motif of modern life.

NOW, gentlemen (you will allow me the forensic style while speaking of my bill? I thank you)—gentlemen, this bill, which I hold in my hand, is aimed particularly at the regulation of the social side of motoring. The purely mechanical matters, the standardizing of wheelbases, the ratio of horsepower to candle-power—these details I cheerfully leave to the experts. But in the direction of social control there is much to be done. Remember, gentlemen, that the automobile is essentially social and rests on that fundamental social unit, the family. Of course, a man may take a spin in the Park or even a little dash to Long Beach without necessarily being accompanied by any near female relatives (applause and cries of "Attaboy!") but one who goes on any extended excursion or tour, sans famille, is a disgrace to American manhood and a menace to the community. (Cheers.)

For a tour is essentially a family affair. It is one of the most intimate associations of married life. Is there anything more touching than the picture of husband and wife poring over the blue-book and the road-map together, planning their first tour?

How lovely it is to hear them lisping the first baby words in the manufacturer's primer! How inspiring to hear them gradually mastering the monosyllabics, "gear," "break" and "clutch," until eventually they are able to refer glibly to carburetors, transmissions and differentials. They have entered a new paradise. Their 1918 Swang-Beezum means more to them than home. This is true of so many. I have seen them on the road—and I know from their looks they couldn't possibly own both a home and an automobile. The inference is obvious. They have made their choice: for them "the life of the open road! The extra shoe and the heavy load!"

My friends, the Paddlefords, told me the other night they had decided to name their latest-model child Ignito, which I thought both modern and attractive. They were discussing their Autumn tour as we dined—tours are invariably discussed at the table—and I was forcibly struck by one of the points which needs regulation and control—and I have made it part of my bill. Paddleford complained bitterly at the color-marking of routes. The maps are printed in colors which correspond to bands painted on the telegraph poles along the way. Mrs. P., it seems, has a passion for blue and has literally forced her husband over nearly every blue mile in the country. There is one blue line which the map shows running through the Everglades that he refuses to attempt, as he thinks it may be a river—but let that pass. It does seem a bit hard on Paddleford. There are thousands of places on the red routes that he is dying to see, but he hasn't a chance.

(Continued on page 116)

(Continued, from page 63)

You know, gentlemen, if you have ever toured, that the decision which road to take when you arrive at any fork or four-corners is one of most terrific import. I have known families to be hopelessly estranged and broken up by it. It seems to be one of these things upon which husband and wife can never agree, like "what is the difference between exhilaration or intoxication?" or "how late is coming home early?" My remedy is simple. Abolish the color system entirely, even removing the telegraph poles if necessary. They are ugly things, anyway, and people are constantly running into them. In these wireless days, poles of any kind are an anachronism. Every car should be equipped with a roulette wheel. Spin it and take the route indicated. Could anything be more delightful? Imagine the surprises, the element of the unexpected. It may be objected that one would never know what his destination was to be. To that my reply is, "Tourists seldom do." At least, Paddleford would see some of his red towns.

ANOTHER vital point in the regulation of the social side of motoring is the control of the hotel situation. This is perhaps more intimately social than any other phase of the subject. Countless hostelries, inns, manors, clubs, etc., are incessantly bidding for the motor trade in clamorous signs which efficiently destroy the natural beauties they boast of. But when they get you, how different is your treatment.

You are simply rated at the face-value of your car. The plain truth is that there is nothing democratic about the automobile world. Look over the local paper in any town on the Ideal Tour, and you will see the paying-guests listed as follows:

Registered at the Axminster—

J. J. McGooey, Pittsburg (Wackhard)

Gustave Liss and Party, Atlantic City (Whiffenpoof, etc.

These are the standards that blight the lives of such as poor Paddleford! He has rolled in, the night before, in his little 10 horsepower Ingersoll, which he has taken around to the garage, lui-meme,— and ambled pleasantly into the lobby under the delusion, poor soul, but that he could hob-nob with the great McGooey and join the Lipp party on sight. Nothing doing. Even the McGooey's chauffeur looks down on him. The magnificent person at the door, who looks like the whole delegation from Siam, simply can't see him. Tired, worried, wondering what's the matter, Paddleford sneaks off to an early bed and is glad to pay his king's ransom in the morning and take to the road again.

It's all wrong. My idea would be to have the big hotels divided into three classes to be known, say, as the Jitney, the Gentile and the Jew classes. The titles are self-explanatory. It should be a misdemeanor for any car owner to register in that part of the hotel to which his car on a purchase-price basis, does not entitle him.

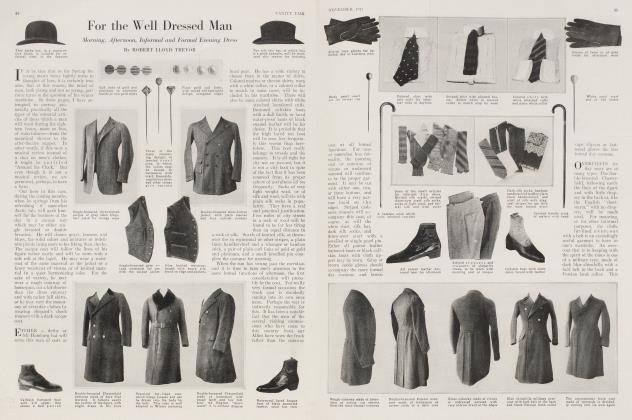

THE vital necessity for regulation will be all the more evident, gentlemen, when you consider the question of clothes. This matter fairly shrieks for control. There is no telling whom you are up against. The clothes of our motorists should be just as much a matter of government regulation as the uniforms of our soldiers and sailors. (Even those I have never been able entirely to understand, but I can come fairly near being right when I remember that khaki is dirt-colored, while blue suggests the bounding main.) How much more satisfactory it would be all round if the get-ups of our motorists were some indication of their particular set! Only last week, at the Bretton Woods, I noticed a machine which strikingly illustrated my point. It had an Ohio license number and it contained, evidently, a family party en tour. The car was an old comb-backed Pulmotor, with a family entrance in the rear, yet there was not a vestige of a dust-coat in the entire party—a thing which, I am sure, would not be tolerated in Ohio! What the motorist should wear, if you will allow me to beau-nash for a moment, is set forth in my bill roughly, as follows: (and note that the costume equipment follows the immutable rule of "the higher the fewer." The lower the horsepower, the more elaborate the make-up).

For the drivers of the lower-priced ready-to-wear machines, a complete equipment of motor clothes is de rigueur. Dust coats and caps of self-color material should be worn at all times. A red-banded cigar adds a snappy note. The entire face down to the cigar, should be covered by an isinglass windshield with ear-flaps. Neither cigar nor cap should be removed in the presence of ladies. While not en route, lunch (sandwich or banana) may be carried in the right hand. For "the wife"—by which title she should always be mentioned—a touch of color is permissible. The head may be covered with a poke-bonnet or hood in the pastel shades of purple, which contrasts so attractively with amber goggles. A dark green or brown veil is distinctly respectable.

IN the second class of motorists ($1,500 to $2,500) I noticed a decided tendency to color. Bodies are lavender, custard-yellow or robin's egg blue—I am speaking of the motors, naturally—and garments should harmonize. Just as these vehicles follow the stream lines of our best bath-tubs, so should the raiment of the passengers be clinging and appropriate. For the lady, who usually drives, a bathing-cap, brilliant sweater with contrasting collar and short sport-skirt are much in vogue. In this class, the gentlemen usually wear trench coats over belted jackets, white or pin-striped flannels and pumps.

Finally we come to the third class, the MidasCroesus set, whose vast limousine show-cases make any special dress almost an impertinence. In fact, it is bad form to wear any garments other than those usual in a Newport day. Among the early styles I note a marked swing toward the corridor compartment type, six rooms and bath, which enables the occupants, en tour, to dress for dinner at the conventional hour.

However, gentlemen, all these points will be very exhaustively regulated in my bill and I think you will agree with me that it will be what is technically known as SOME bill. And when it comes before Congress, I am sure that I may count on your vote, one way or the other. I thank you.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now