Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

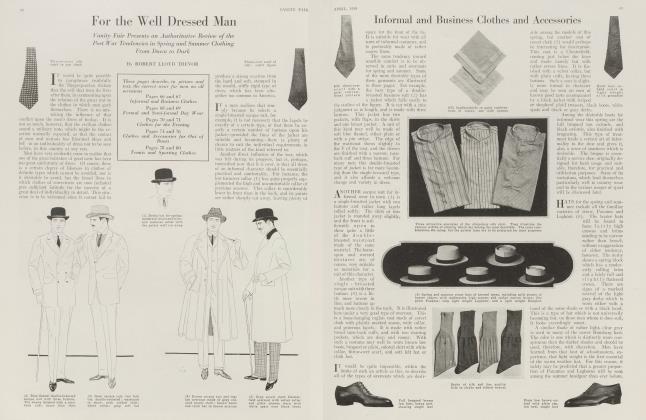

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowFOR THE WELL-DRESSED MAN

The Passing Dominion of London

ROBERT LLOYD TREVOR

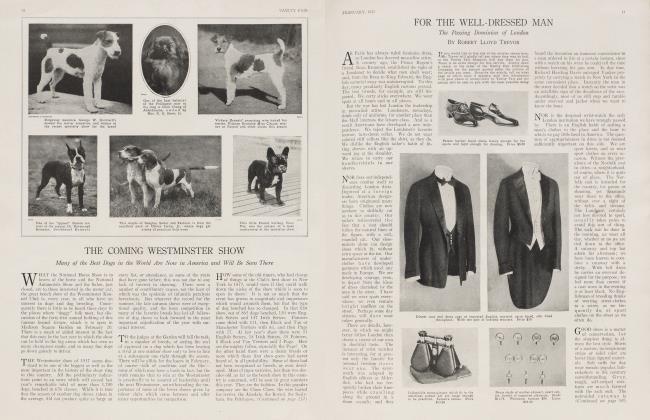

AS Paris has always ruled feminine dress, so London has decreed masculine attire. A century ago, the Prince Regent's friend, Beau Brummel, established the right of a Londoner to decide what men shall wear; and, from the Beau to King Edward, the English sartorial sway was uninterrupted. To this day, many peculiarly English customs prevail. The best tweeds, for example, are still imported. We carry sticks everywhere. We wear spats at all hours and in all places.

But the war has lost London the leadership in masculine attire. Londoners, nowadays, think only of uniforms, for another place than the Mall interests the leisure class. And as a result Americans have developed a new independence. We reject the Londoner's favorite narrow, turn-down collar. We do not wear colored stiff collars like the shirt, as they do. We dislike the English tailor's habit of fitting sleeves with an upward jog at the shoulder. We refuse to carry our handkerchiefs in our sleeves.

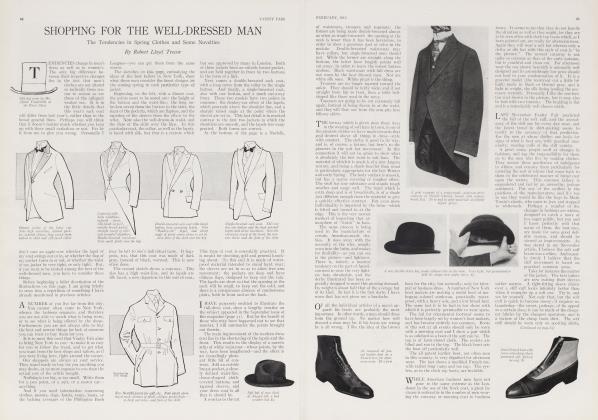

NOR does our independence confine itself to discarding London dicta. Deprived of a foreign leader, American designers have originated many things. Clothes are now nowhere so skilfully cut as in this country. Our tailors rediscovered the fact that a coat should follow the natural lines of the figure, with a soft, rounded cut. Our shoemakers alone can design shoes which fit, without extra space at the toe. Our manufacturers of underclothes have developed garments which excel any made in Europe. We are developing courage, even, to depart from the ideas of dress cherished by the man in the street. I have said we wear spats everywhere; we even venture bright mufflers on the street. Perhaps some day citizens will dare wear colors generally.

There are details, however, in which we might better follow London than choose a course of our own in doubtful taste. The instance of wrist watches is interesting, for at present only the fanatic for personal freedom dares wear one. The wristwatch was adopted by English officers at Aidershot, who had too frequently broken their time-pieces while crawling along the ground in a sham assault; and they found the invention an immense convenience to a man ordered to fire at a certain instant, since with a watch on his wrist he could tell the time without lowering his gun arm. In due time, Richard Harding Davis outraged Yankee propriety by carrying a watch in New York in the same convenient place. Instantly the man in the street decided that a watch on the wrist was an infallible sign of the decadence of the race. Accordingly, most of us still stop and fumble under overcoat and jacket when we want to know the hour.

IF you would like to buy any of the articles shown here, Mr. Trevor will gladly tell you where they may be had, or the Vanity Fair Shoppers will buy them for you. There is no extra charge for this service. Simply draw a check, to the order of the Vanity Fair Publishing Company, for the amount quoted under the picture of the article you want. Describe the article, tell on what page of which issue it appears, mail this information with your check or money-order to Vanity Fair and the article will be sent to you with the least possible delay

NOR is the despised wrist-watch the only London institution we have wrongly passed by. There is an English habit of suiting a man's clothes to the place and the hour to which we pay little heed in America. The question of appropriateness in dress is not deemed sufficiently important on this side. We are sport lovers, and so wear sport clothes on every occasion. Witness the prevalence of the Norfolk coat in cities—a neighborhood, of course, where it is quite out of place. The Norfolk coat is intended for the country, for games or shooting, yet thousands wear them to the office, without ever a sight of the fields and streams. The Londoner, certainly not less devoted to sport, usually takes pains to avoid this sort of thing. The sack suit he dons in the morning, we wear all day, whether or no we are tied down to the office. A cutaway and top hat adorn his afternoon; we have been known to combine a cutaway with a derby. With full dress he carries an overcoat designed for the purpose; we feel more than correct if a coat worn in the evening is at least black. No Englishman of breeding thinks of wearing street-clothes to a soiree, as we frequently do, or sport clothes on the street as we often do.

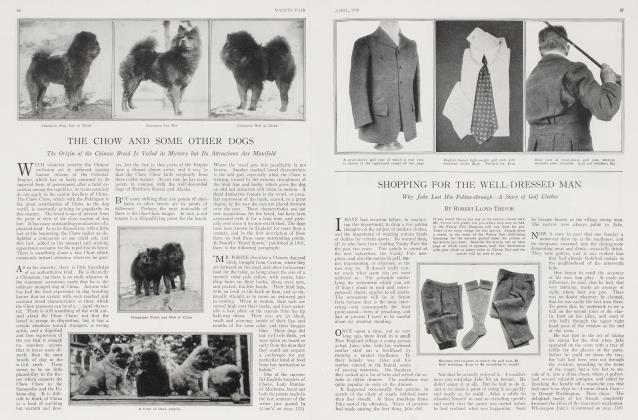

GOOD dress is a matter of conservatism, for the simplest thing is always the best style. Shirts of a narrow, inconspicuous stripe or solid color are better than figured materials. Soft cuffs for day wear remain popular, haberdashers to the contrary notwithstanding. Gray, rough, self-striped mixtures are much favored with the sack suit. The unbraided cutaway is preferable to one with braided edges. With formal afternoon dress a "V" front turn-down collar is more liked than the old wing. The scarf-pin consisting of a single pearl is the only one much worn. Cloth top shoes, if worn at all, should not be worn with a sack suit. Pearl-set watch chains belong only to evening dress. And these are but a few details noted at random from the list of sartorial items which are good style because they are the simplest things procurable.

Continued on page 98

Continued from page 77

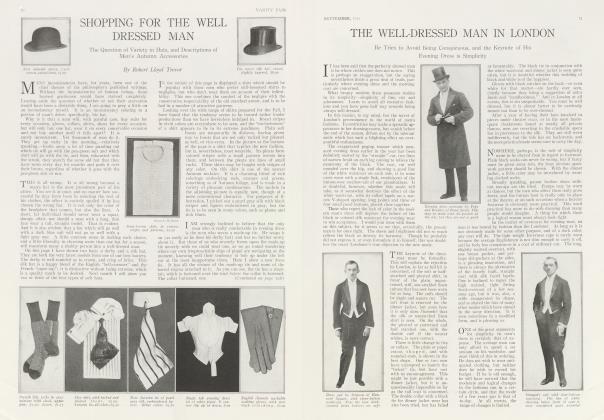

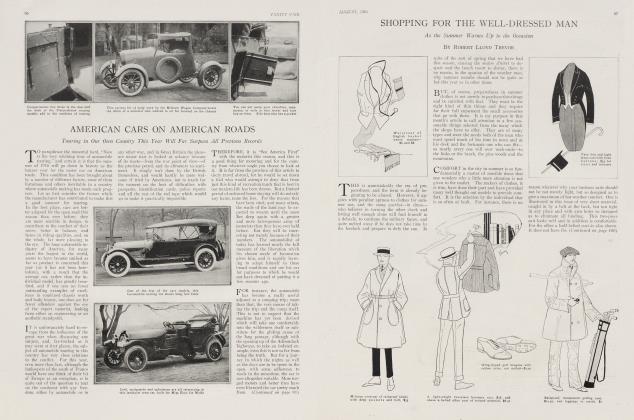

EVENING clothes, it has always seemed to me, are peculiarly important—not only because ill-chosen dress attire is more unfortunate than heedless informal clothes, but because evening clothes give most men in America their only mental rest. Sport clothes relax the tense mind of the business man, it is true, but sport is largely a matter of warm seasons. Evening clothes occur nightly, and it is a fact that as the average man slides into his dinner coat he slides out of his daytime cares.

The traditional opera hat, which has lately lost most of its popularity, was a priceless convenience in rainy weather. Its heavy silk was not easily spotted, for one thing, and then too, its collapsible body was a godsend in the taxicab and hardly less of a boon if one had not a box at the performance. But even the opera hat has been war blighted. The springs concealed beneath its innocent exterior have always been manufactured in France, and the fact that they are not now made there has resulted in a total famine in these hats. A silk hat, then, is the only possible head-gear for formal wear, in spite of the fact that its delicate and easily tarnished surface makes it an annoyance in any constricted space. Largely for this reason, a soft black felt is frequently worn with a dinner coat.

ANOTHER modification of strict form for comfort's sake is the newer collar, for wear with a Tuxedo. The standing collar, perhaps with a wing, is still necessary for full dress, but with informal evening wear a low, turn-down collar with "V" shaped opening is seen everywhere.

White pique remains the correct material for a waistcoat intended for formal evening dress; for the dinner coat, however, the black waistcoat is nowadays more often met with. It should be of a dull heavy silk, however: the waistcoats of watered or figured black silk, shown by many haberdashers for wear with the dinner coat, are not seen among conservatives.

THE thousand-pleat shirt observed even with full dress, at the height of the dancing craze, is now a very dead issue. But a mildly pleated shirt is both comfortable and correct for the informal evening turn-out.

JEWELERS show a thousand gorgeous sets of evening studs, elaborate designs, many of them of onyx and pearls, or onyx and diamonds. But for formal wear one type of stud is especially popular—a simple white mother-of-pearl with perhaps a pearl center. For the dinner coat a stud of black and white, a quiet onyx with platinum border, is possible. The smoked pearl stud is not so much favored. But whatever the material of your studs, the effect must be one of extreme conservatism. In all cases, any diamond setting is to be frowned upon.

WITH full dress the correct shoe is a high or half-height patent leather. Pumps for any function other than dancing are hardly desirable. A laced patent leather low shoe with reasonably heavy sole, like the one shown on page 77, may be worn with full dress and is a happy medium for any affair which combines dinner or supper and dancing. The advantage of the shoe illustrated is that it may be worn for short distances in the street.

THE overcoat for full dress must be black, a Chesterfield, or a coat of fur. Older men wear capes, after the European fashion. But with the dinner coat all sorts of top-coats are popular; often a gray covert cloth or tweed is permissible, in any but the coldest weather. The muffler must be white, or, best of all, pearl gray; for colors are somehow not suited to even the small details of evening dress.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now