Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

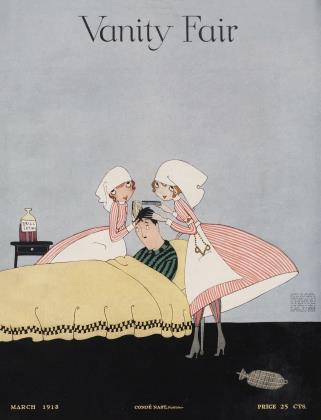

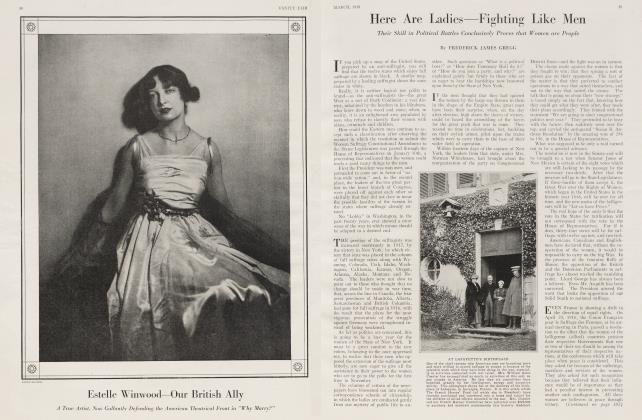

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowA Fashionable War-Time Wedding

And the Need for Control—Whether Personal or Governmental

GEORGE S. CHAPPELL

POOR old Ned Townsend. It's a frightfully sad case. Fancy going off your head, and just after carrying one of the gentlest, sweetest— But I ought really to begin this story a little further back—back where the problem of control really started.

Dear little Ned! How well I remember him in his early boyhood. He was always considered rather uncontrollable. Not vicious, but quick and impulsive, prone to act upon instinct rather than reflection. I shall never forget the day, years ago, when he pulled the front legs out from under the grandfather's clock which stood on the stair landing of the Townsend's house on Washington Square. It made the most gorgeous crash and scattered wheels all over the lower hall. I thought he would be murdered, but his mother was very placid and only said, "Dear Edwin! he meant no wrong; he only lacks control."

Yes, he lacked control, and, as he grew older, he lacked it more and more. He put away the things of childhood— such as grandfather's clocks and rosewood music-boxes—and took unto himself the destruction of more serious and vital things, such as a fortune left him by his grandmother. He also set about destroying his own health,—but that was with the artful aid of alcohol, of course.

Soon, Ned's club-bills grew perfectly enormous and soon after that he began to look very hollow-chested and anemic. Then the unbelievable happened. He began to show signs of control.

The first time I noticed it was one day at the club just after America had gone to war. A waiter entered at the other side of the room and, to my utter dumfoundment, Ned did not ring the bell. You could have knocked me down with a cocktail!

AFTER this first shock I was prepared for almost anything. It was so abnormal in Ned that I was not at all surprised when Professor Daniel McMullins, the club chemist, paused, at the bar, in his experiment on the reaction of Plymouth gin to Italian vermouth and said, "I hear that Mr. Townsend has gone to Plattsburg."

Of course, he had.

Everyone who hadn't an incurable spavin, or a rush of family to the breakfast-table had fallen in line as might have been expected.

But, believe me, I was totally unprepared for the specimen of manhood that greeted me in September when the Plattsburg camp was over and all the commissions awarded. We unfortunate stay-at-homes had worried about poor old Ned. It didn't seem possible that a man who always claimed that daylight hurt his eyes could survive three months of compulsory bed-time. Imagine our feelings, then, when a two hundred pound bomb of energy dropped into the midst of our little circle, bursting with health, strength and a ninety-day thirst. We were tremendously glad to see him, and we shook hands all round several times, but I could tell that something was worrying him. There was some great need gnawing at his soul. Finally he backed me off in a corner and whispered hoarsely.

"Do you suppose you could get me a Scotch and plain water?"

Would you believe it, Professor McMullins. was obdurate, said it couldn't be done, he might lose his license, Washington controlled all the alcohol, and so on. "But," he added, with fine irony, "If you were to order a clysmic for Mr. Townsend, sir. . . ."

It seemed too ridiculous, but I ordered the clysmic and Ned drank it, then and there.

And that was another shock to Ned, and another evidence that the Government was getting its fine Italian hand in.

It was undoubtedly this change in Ned's routine that led him, via the tea-and-toast route, to the arms of his lady .fair. Tea, when all is said and done, is a feminine beverage; its presence connotes a quiet parti-a-deux, the alluring strains of a valse lente and an exchange of sentiments sweeter than the patisserie that so often accompanies them. After having seen Ned, on several occasions at Sherry's, discussing the mysteries of Ceylon with that sweet and gentle Margaret Sackett, I was thoroughly prepared for the viselike grip which preceded an announcment from him to the effect that he had great news for me.

"I know," I answered coldly, "you are engaged."

"How did you guess it?" he asked. "Tea," I answered cryptically.

Of course, he wanted me to be his best man-. Have you ever noticed that a groom invariably selects, for this solemn office, one to whom his horrid past is known in every detail ? I suppose he figures that it is safer to have such an one—or such a one, as the reader may prefer—in the cast than in the audience.

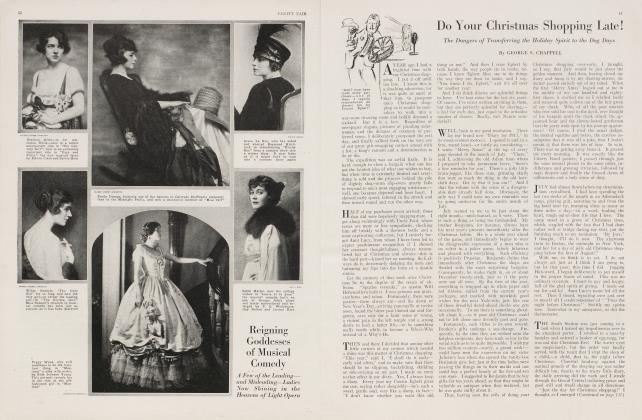

THE wedding took place during the first furlough, just after the holidays.

By that time, as you will remember, Washington had .had a taste of Government control, and had learned to like it.

It was all a terrific strain on poor Ned. The invitations were sent out in the usual rush which surrounds a warrior's wedding. So much so that an exceptionally large number of intimate friends and solvent relations were wholly forgotten. At every turn some new obstacle of control loomed up to thwart his nuptial plans. The first governmental jolt was the wedding-breakfast menu submitted by good old Frederique the caterer, as the date selected turned out to be meatless, heatless and wheatless,—and practically eatless. Champagne was out of the question; Ned's prospective father-in-law being a total abstainer, and chairman of the Make-your-own-barley-water Committee, with a Thrift-stamp booth in his office vestibule, and Red Cross buttons pinned all over his evening clothes.

Continued on page 100

(Continued from page 54)

Frédrique was in despair.

But nothing about food really mattered, for when the wedding finally came no one could eat much of anything as they were all too closely bundled up in their arctics and furs.

Just the day before the wedding Dr. Garfield suddenly decreed that the day we had chosen should be coalless as well as all the other little things.

AS a result of Dr. G.'s happy inspiration the little side-chapel at St. Thomas's, where the ceremony was to be performed, looked like the Mammoth Cave. It had lovely and impressive stalactites of ice hanging down from the arches. The ushers wore trenchcoats, trimmed with the conventional skunk, and were allowed, by special dispensation of Dr. Cook, the rector, to keep their hats on. As the cortege trooped silently up the aisle—the organ having unfortunately been frozen during the night,—the stalwart soldiers followed by the bulky bridesmaids carrying ermine muffs, the scene somehow reminded me of a picture I had once seen of an Esquimaux community on the move.

Ned's ear-tabs prevented his picking up his cues as well as he had done at the rehearsal and I contributed my share to the general nervousness by letting the ring —because of frostbitten fingers—get loose in my left mitten.

It was all very trying and we were quite thankful when the wedding was over and we were back at the house again, munching Fréderique's delicious Biscuit de Bran à la jeune Mariée.

IT was when I had gone upstairs to perform, with a corkscrew, a few last mysterious rites for the benefit of the groom that I began to appreciate that the poor fellow's mind was crumbling. I saw that "control" was slowly but surely getting him. He came rushing out of the room where the presents were lying in state. I noticed that he was laughing wildly.

"Have you seen this?" he screamed, thrusting a book into my hand, a bride's-book in which the wedding presents and their donors had been carefully entered by Margaret's Aunt Sarah.

A glance at the page before me, and a hasty survey of the room back of Ned, flashed upon my mind a picture of what had finally crazed him. All the presents were useful presents, and especially useful in war-time.

Fascinated, I scanned the list. .

Mr. and Mrs. Griswold Cruger, one bucket of stove coal.

Mr. Astor A. Barney, one ditto, with brass-tongs. Mrs. Ogden Alexander, one Little Giant oil-stove. Mrs. Lispenard Iselin, one gallon gasolene.

Mr. Stuyvesant Lenox, a brace of tallow candles. The Misses de Peyster, six (6) lumps of domino sugar.

Mr. and Mrs. W. K. Harriman, one small barrel of flour.

Miss Harriette Wiborg Canfield, one small porterhouse steak.

I WAS interrupted by a low moan from Ned. He was foaming at the mouth. It took the combined efforts of myself and the detective (who had been guarding the valuable buckets of coal) to force Ned into the guest-room and then to the Post Hospital where the doctor in charge, only this morning, assured me he was making excellent progress.

He really hasn't been the same again since. He goes on raving, in the most extraordinary way, about the price of coal, about the lack of heat, about the inability to get a private car from the Pennsylvania Railroad to ship him and his bride over their tracks to Washington, where he had planned to spend the honeymoon. Added to all this, it seems that his feet were badly frostbitten at the recent flurry at St. Thomas's. Two of the bridesmaids are at the Roosevelt Hospital, suffering from severe cases of pneumonia. The bride's family are still keeping two detectives to guard the wedding presents.

This evening I called up the hospital again, merely to see how the poor chap was doing. It seems that his condition was on the whole a bit better. He is breathing regularly and able to recognize his bride at odd intervals. The family had all taken hope.

"It was just a case," the doctor said, "of too much control. We have many cases like his. It would seem that some men are born with control, others achieve control, and still others have it forced upon them by the Government. Your friend evidently belongs to the latter class."

How true,that was! What a marvellous diagnosis! And how many millions of us are suffering from exactly the same complaint.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now