Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Advent of Every-Day Flying

What Is Happening in American Aviation and What Is Going to Happen

GEORGE W. SUTTON, Jr.

DID you, by any chance, see this in the newspaper the other day?

WASHINGTON, June 2.—The War Department published the following army orders today:

AIR SERVICE

Clune, 1st. Lt. E. A., from Washington to New York, by rail, thence by airplane to San Francisco, to take part in transcontinental flight and will return by airplane to Washington, D. C.

And did you see, also, a news item stating that a company headed by Lieut. Wesley Hill had established an air bus line over the Apache Trail across Arizona and California, consisting of six Martin airplanes carrying twelve passengers each, to take the place of the old motor bus line?

Those two things give a remarkably sharp mental silhouette of the progress and possibilities of our rapid strides in becoming familiar with the element which has baffled us for so long—the air.

If you did read of them in the papers, they occupied your thoughts for only a few seconds. Such is man's ability to become accustomed to changed conditions! Five years ago the airplane was new, interesting per se. To-day it is accepted as a fact. To-morrow's developments are regarded as certain; in many cases, indeed, they are erroneously regarded as already accomplished. A man flies across the ocean. It creates interest but no particular wonderment. It takes on the aspect of an international race and thus becomes a sporting event. We should consider it no marvel if an aviator flew around the world in an hour. We simply say to ourselves that air travel is here; that it is quick, efficient, still a little risky, but practical and feasible—and that's all there is to it.

But before air travel becomes even what we think it is already, there is a long, painful path ahead of it. And if American aviation is not to become again the absolute zero it was before we entered the war, heroic measures are necessary.

Professor Langley, in 1896, discovered the principles of mechanical flight. He was regarded by the public as harmless but rather demented. The Wright brothers were the first to apply his principles and actually fly, in 1903. Their marvelous work got no reception or encouragement here, so, after a wh'le they were forced to seek recognition in Europe. And there they found it. Great strides were made on the continent in the flying art and the Wright brothers gave an added impulse to aviation—in Europe.

The inevitable resuit was that when we entered the war we were not ready. Other nations, even Siam and Servia, were miles ahead of us in aviation. Our air fleets did not exist. Our technical knowledge of flying was in an almost similar condition. At first we did not know how far to go in the direction of developing our air forces. Then, upon the urging of the French commission headed by Marshal Joffre, the Government began to get busy and enlisted a hundred million dollars of private capital which was invested in elaborate plants in expectation of the huge orders to come. They came, commencing with a Government appropriation of something like $648,000,000. Tremendous and wholly impossible promises of huge air fleets to fill the ether within a few months were made and given the widest publicity. The mechanical brains of the country were united toward the creation of an ideal, standardized motor. They were called upon, also, to produce in great quantity American adaptations of what appeared at that time to be the best planes in use among the Allies. The result was a marvelous motor under the popular name of "Liberty"—and the greatest production feat in history was begun.

(Continued on page 68)

(Continued from page 49)

We were still beginning when they called the war off. It was a mighty beginning, however, and we had done enough by Armistice Day to show ourselves and the world our tremendous possibilities. Among other things, we had created a huge new industry.

Then, with the coming of peace, this infant industrial Colossus, only two years old, was left flat. And it is flat to-day.

There are two possible—and probable—life savers; two agencies which, unless all signs fail, are going to keep our aviation industry going and expanding so that when we go into the next war we shall not go in as we did before—unready—in the matter of aircraft. These are:

1. The Government.

2. Commercial Flying.

It will be years, three at least, before commercial flying will begin to take care of the great aviation industry. Therefore, the Government must step in and, with orders for new and present types of combat 'planes, mail 'planes, and so forth, tide the industry over. Luckily, the War Department has a man at the head of its Air Service, Major General Charles T. Menoher, who sees this situation very clearly and is determined that American aviation shall live—and live a healthy life. He had the opportunity to realize, when he commanded the Rainbow Division in France, just how useful a well equipped air service might have been to a division commander. He says, in a recent interview in the New York Globe:

"I believe that there is a wonderful future for commercial flying in this country; but if we exaggerate its possibilities we will do the industry as much harm as if we underrate them. I do not believe that the airplane will be used for general passenger service on a big scale for at least a generation. * * * Airplane service must always cost more per mile per passenger than railway service. In the same way, the use of the airplane for freight will be confined to lightweight luxuries which are of high value per ton. The few less valuable commodities to be carried by airplane will be among highly perishable products.

"Another possible disappointment for the enthusiast who thinks aviation is to be the greatest industry of the country has to do with the establishment of aerial routes. General cross-country flying will, I am convinced, be limited to highways of the air between the larger cities. Railroads exist to-day only between towns where it is commercially advantageous i to have them. The same thing will be true of the airplane. Persons living in remote parts of the country will see them almost as infrequently as is now the case."

(Continued on page 70)

(Continued from page 68)

To many this will sound ultra-conservative, for results being attained right now in American aviation are large and important.

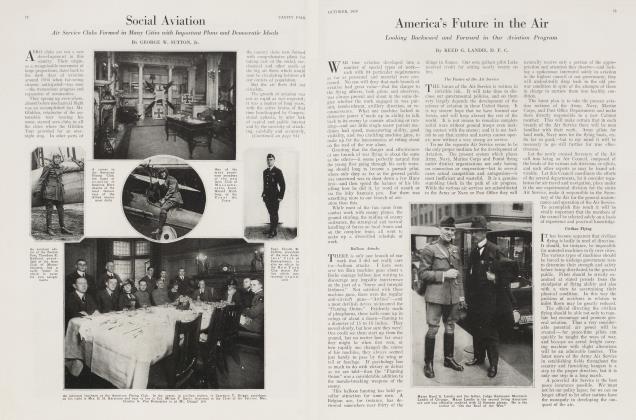

Already we are building 'planes vastly superior to any we constructed during the war. From all parts of the country—and the world—come reports of the adoption of the airplane for new and unusual uses. Here a 'plane is crossing the continent in 24 hours. There a doctor is calling on a distant patient by airplane. The Los Angeles Fire Department has an aviation department for fighting waterfront fires. The New York police are well organized with aviators and equipment. The College of the City of New York has added a course in aeronautics. Patrols have been established to discover and fight forest fires with airplanes. Mail and farm products are being delivered by aerial post. An expedition is forming to explore and chart the South American rivers. A minister is preaching to his congregation by wireless telephone from two thousand feet in the clouds. Numerous loving couples are eloping and honeymooning by airplane. A daring acrobatic aviator is jumping from one 'plane to another in midair. And so on and so on and so on.

But to keep this vital asset of ours from passing out, many things are needed, among them great public interest in flying and hundreds of municipal landing fields. Above all, Congress must, immediately, without its usual delay, come to the rescue in a tangible, substantial manner.

It will be Vanity Fair's endeavor, through these articles, to keep its readers thoroughly informed on what is going on in aviation with the newest photographs of the newest 'planes and the most prominent men and women interested in flying, interesting articles by people who know most about the question and, through the co-operation of the Manufacturers' Aircraft Association, to answer any questions readers care to ask about any phase of flying, past and present.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now