Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowOur Auction Bridge Refuge

A Sanctuary and Retreat for Persistent, Not to Say Incurable Bridge Addicts

R. F. FOSTER

THERE is a certain class of players who must have a rule for everything. Give them rules by which they can measure up a hand, just as one would measure the height of a wall or the width of a door, and they feel confidence enough in their system to be sure they can get over or get through. Some call this playing bridge by machinery.

But the opening leads have been reduced to just such a mechanical system; so have all the second-hand plays, echoes, discards, and all that sort of thing. No one calls that playing bridge by machinery. There are others who tell us there is no absolute "never" in bridge, especially in the bids. In spite of this, there are five simple "nevers" that will stand the beginner in good stead if he will stick to them.

1.Never make an original bid without two sure tricks in the hand.

2.Never bid hearts or spades without length, as well as tops; or tops as well as length.

3.Never double to get a bid out of a partner who has already passed up a free bid.

4.Never overcall a no-trumper on your right unless you can go game on your own cards.

5.Never leave your partner in with a notrumper if you have five cards in hearts or spades.

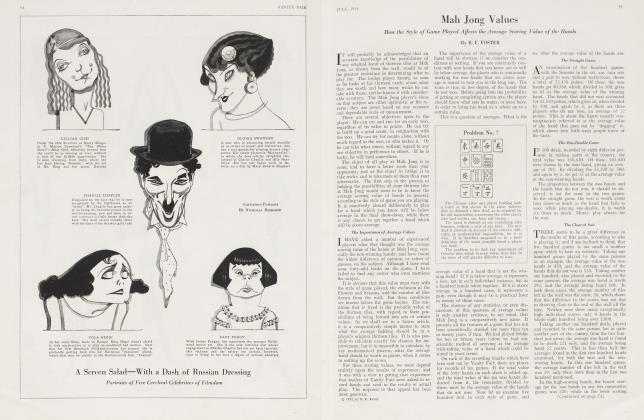

Here is a deal in which no less than four of these points are illustrated:

Z deals. Not having the tops in spades, he does not bid on the first round. This is in accordance with maxim No. 1. A bids a club, Y refuses to double, following out the third maxim, and avoiding a very common error.

B is encouraged by his partner's club bid to take a chance on no-trump, and Z suppresses his intended secondary bid in spades, following out the fourth maxim.

On the play, Y and Z save the game, as they make five spades at once, and may make a club later. Z can make two odd in spades, but he would never get the chance if he bid it. Let us see what happens if these maxims are not followed.

If Z starts with a spade, A and Y pass, B doubles, and A says two clubs. If Y helps the spades, B bids three clubs, and if Y goes to three spades, thinking Z has two sure tricks somewhere, he is doubled and set. B can make three clubs. Z's error, maxim No. 1.

If Z passes, A bids clubs, and Y doubles, B passes, Z bids spades, and B goes to three clubs, which he makes; or sets the spades, if they go to three. Y's error, maxim No. 3.

If there are no bids but clubs and no-trump, and Z bids spades, B goes back to clubs and scores. Z's error, maxim No. 4.

Answer to the August Problem

Hearts are trumps and Z leads. Y and Z want all seven tricks. How do they get them?

Z leads the club king, A covers, Y trumps and leads a trump, Z and A discarding diamonds. Y leads another trump, on which B discards a diamond, Z and A shedding small spades. Y then leads the spade.

If B discards a club instead of a diamond on the trump lead, the reason for the original lead of the high club becomes apparent. Z can get in on either spades or diamonds and lead the club through A, who must cover, as B cannot protect the suit.

Problem VI.

Here is an instructive little no-trump ending. Solution in the October Vanity Fair:

There are no trumps, and Z leads. V and Z want seven tricks. How do they get them?

THERE is a further use for the conventional two-trick bid in a minor suit, which was explained in last month's Vanity Fair, and that is to force the partner to pick a suit, and practically to prevent him from going notrump. This form of the convention is not usually resorted to unless the dealer is able to support either of the major suits.

The convention explained last month was to bid two in clubs or diamonds when that was the only weak spot in an otherwise good notrumper. The extension of the convention is to bid two tricks in clubs or diamonds when it is highly improbable, if not impossible, for the partner to have the suit stopped twice, the dealer holding the high cards in it himself.

The first use of this convention is to get a no-trumper from the partner, if possible, as he will go no-trumps if he has the tops in the suit named by the dealer. When the dealer has the tops himself, it is impossible for his partner to go to no-trumps, and he must pick a suit. If this is a major suit, that is just what the dealer wants. If it is the dealer's weak suit, the idea is that the dealer himself can go to no-trumps, trusting his partner for that suit. To illustrate, take this distribution:

There are three bids open to Z on these cards if he is the dealer. He can bid no-trumps and take a chance on the clubs. If he does, he will lose five tricks in clubs and the ace of spades. He can bid two clubs, to see if Y can protect that suit for him. This Y will answer by bidding the higher ranking of two suits, spades. If he is not so particular about the rank of the suits, and prefers the slightly stronger diamonds, Z will leave him in, and Y will make five odd at either declaration.

The other way to bid the hand is for Z to start with two diamonds, so as to force a suit bid from Y, as it should be a good shift to notrumps if Y calls the clubs, and a game hand if Y has four hearts or spades.

Now comes the point. Y cannot tell which end of the convention the dealer is using, and as he has not the required tops in diamonds, he will have to bid the spades. The weak point in this convention, as will be seen presently, is the possibility that Y might have only one four-card suit, clubs, and bid that.

To illustrate, let us transpose the hands of A and Y, and Y will have to call his five-card club suit, and will have to bid three. The student will notice that Y does not know whether the two diamond bid is from strength or weakness.

B would double three clubs, as this is the conventional defence, to show where the tops in clubs really are.

(Continued on page 92)

(Continued from page 61)

If Y is left in, he will be set for 300. If Z tries to pull him out he will set for 200 or 300 on anything he calls.

Suppose he tries no-trump, he is set for 200, as either A or B would double that contract. If he goes to three spades, the higher ranking suit, he will be doubled and set for 300. If he picks the hearts, he will be set for at least 200. This would indicate that if Z were using the convention with A's cards opposite him, instead of Y's, the two-diamond bid would turn out very badly. If he were fortunate enough to find B's cards opposite him, instead of either A's or Y's, a three-club bid, overcalled by Z with three no-trumps, would make five by cards very easily.

If there were any way in which the bid could be made by the dealer so that the partner should know whether it was from strength or weakness, this convention would be one of the most useful in the game. As it is, many players consider it has two to one in its favor, as two out of the three other hands must fit. Some insist it is a three to one chance, as there are three suits to pick from out of the four.

Hard Luck Hands

SEVERAL persons have been kind enough to send to VANITY FAIR some of their experiences with hard luck hands. Here is one, in which the position of one card makes a difference of 714 points. The distribution and remarks on the original bid and play are by Mrs. H. J. Dangerfield, of Chicago.

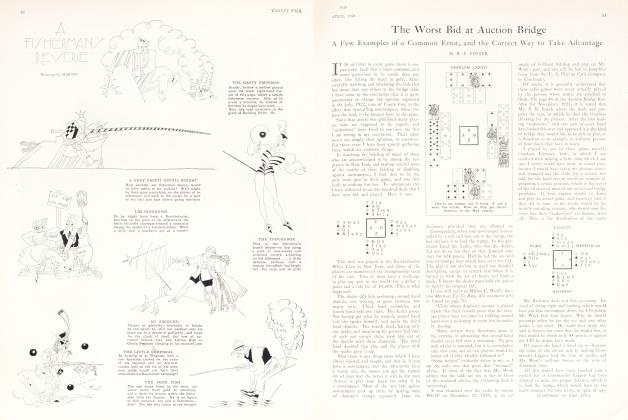

Z dealt on the rubber game and bid a heart, A a spade, and Y two hearts. B went to two spades and Z to three hearts, which A passed, but B doubled. That ended the bidding, as A was doubtful of game in spades. The heart contract was set for 300. This was the play:

The opening lead was the spade king, which Z trumped. In order to get the finesse in trumps over B's double, Z tried to put dummy in with the finesse in diamonds, the queen falling to B's singleton king. B returned the spade, and Z trumped it, leading another diamond to dummy and finessing the ten. This B trumped.

A third spade lead forced Z to trump again, as to pass it would only allow A to give B another ruff in diamonds. Z then led two rounds of trumps, and A blanked the king of clubs, as it was clear that Z's supporting suit was clubs, and a finesse in that suit was inevitable.

Any diamond that Z leads now is covered by A, and B trumps the ace. Another spade is overtaken by A, and forces the last trump from dummy. The club finesse lets in a diamond and two spade tricks, setting the contract for 300 points. "This is all due to two blank kings winning tricks."

While one must agree with the concluding remark, the interesting part of the hard luck in this hand is the fact that if we transpose the king and jack of diamonds, leaving every other card just as it is, Z will win the game and rubber by making four odd, whether at double value or not. At the double value, this would be 64 in tricks, 100 for a trick over a doubled contract, and 250 for the rubber, the honors remaining the same as when Z was set for 300. The difference is 714 points.

The play would be as follows: Z trumps the king of spades, but the diamond finesse holds, the queen dropping the jack from B, and marking him with no more. Three rounds of trumps follow, leaving B with the lone queen, and Z with the ace. The finesse of the ten of diamonds forces the losing trump, and leaves Z with a trump to stop the spades later on. When B leads the spade, Z passes it up, so as to establish the queen.

Now, if A leads the diamonds he loses two tricks in that suit. The same thing in clubs. He leads the spade, and makes the king of clubs. Now Z can trump the spade, put dummy in with a diamond and finesse the club ten.

DURING the warm weather Mrs. Cadmus-Brown had several opportunities of enlarging her knowledge of the way they play bridge in the East. Her friend Mrs. Blythe asked her to make up a little rubber for penny points in a hotel parlor at Atlantic City, with two men who were too warm to do anything else.

Mrs. Blythe was from the same town as Mrs. Cadmus-Brown, and they knew each other's game from the first bid to the last honor score, so it was not to be wondered at that they inwardly chuckled when they cut each other for partners the first rubber. The situation was so attractive, in fact, that Mrs. Cadmus-Brown put on her best smile and tentatively proposed that they play a set match for the evening, the two ladies against the two men, which was readily agreed to.

Feeling perfectly at home with her partner almost for the first time since she came East, Mrs. Cadmus-Brown abandoned her fan, drew her chair close up to the table, and prepared to show the two men what two women from the West knew about bridge. Nothing could beat her system when she had a partner that played her way?

The men were rather quiet individuals, down at Atlantic City for a rest. One was a tall thin Philadelphia lawyer, about forty, decidedly jimberjawed, who held his cards very high, leaned well forward over the table, and brought his right elbow on a level with his wrist when he ran over his cards before selecting one to play. It looked to Mrs. Cadmus-Brown as if his own hand prevented him from seeing his dummy.

The other man was very stout, apparently about fifty, and wore his glasses so far down on his nose that he could look over them simply by lifting his eyebrows, which he did every time any one made a bid, as if he did not believe such a declaration possible.

Somehow, the cards held by the ladies did not fit, or the Western system was not working smoothly, or something was wrong, as they lost four straight rubbers. That they should just miss game by a trick every now and then could not possibly be due to overbidding or bad play, as they understood each other perfectly, and, as Mrs. Blythe assured their adversaries, had always had wonderful success in their home town out West.

The stout gentlemen with the glasses proposed once or twice to change partners, as the "luck" seemed to be running all one way, but the ladies would not hear of it. The lawyer had no remarks to make about anything, and did not seem to care who he played with, as long as he could play.

With a game apiece, and the ladies about two hundred points behind in the honor score, on account of their penalties, the Philadelphia lawyer had the deal. After a careful examination of his cards, with a rapid mental addition of the score, he announced three hearts, at which Mrs. Blythe, sitting second hand, looked as if she had lost all her friends, while the stout gentleman shook his head dubiously, and prepared to spread dummy's cards on the table, as if there was going to be trouble.

(Continued on page 94)

(Continued, from page 92)

The expression on Mrs. Blythe's face, which may or may not have been part of the home-town system, deterred Mrs. Cadmus-Brown from any declaration she might otherwise have intended, as she had always maintained that anything like a preemptive bid in hearts meant weakness in spades.

This was the distribution:

The opening lead by Mrs. Blythe was the deuce of diamonds. They do not believe in fourth-best leads where she came from, as they do not see the use of it. The stout gentleman laid down his cards with great deliberation, and remarked that he was sorry he had the ten of clubs, or it would have been a perfect Yarborough. Mrs. CadmusBrown began to regret that she had not called three spades, as she saw her nine of diamonds taken by the jack.

After the lawyer had turned the trick down with more than usual deliberation, and had studied the situation for fully a minute, the jimber jaw being pushed a little further forward than usual, and his cards being held a trifle higher, while his elevated right arm and hand pushed them forward and back, as if to be sure he had twelve left, the ace of diamonds was finally laid on the table.

Mrs. Blythe played the five, and dummy a small heart. Without a moment's hesitation Mrs. Cadmus-Brown put down the trey of diamonds, gathered the trick herself, and placed it face down in front of the lawyer, at the same time remarking with some acidity: "Dummy's lead. Dummy took that trick."

The stout gentlemen glanced at her over his glasses with more than the usual elevation of the eyebrows, while the lawyer simply thanked her, and placed the trick with the first one. Then he remarked very quietly, "I believe it is dummy's lead."

"Yes," replied Mrs. Cadmus-Brown, settling herself more firmly in her chair. "Hearts are trumps. I suppose you thought you were playing a no-trumper."

Whatever the lawyer thought he was playing, he made no remark, even in. response to the shifted glance of his partner, but led a small spade from dummy, on which he successfully finessed the ten. He then led the king of diamonds, and once more played a heart on it from dummy.

THIS time Mrs. Cadmus-Brown took pity on him, and reminded him that hearts were trumps, and that it was his own trick he was trumping, offering to let him take back dummy's card, which induced the stout gentleman to give his partner the full benefit of the greatest eyebrow elevation of which he was capable. It was bad enough to have a Yarborough without trumping perfectly good aces and kings.

The only response that this brought from the lawyer was the remark, "I believe it is dummy's lead again." Then he led another spade and finessed the queen. Having taken home that trick and turned it down he proceeded to lead out three winning trumps. Then he laid down the ace of spades, and offered to concede the rest of the tricks, taking four by cards, game and rubber, with eight honors.

"Well, I have played a good deal of bridge," remarked Mrs. Cadmus-Brown, as she settled her score, "and I have seen players trump their partner's aces by mistake sometimes; but I never saw any one deliberately trump both ace and king. We don't play bridge that way where I come from."

The lawyer smiled blandly as he picked up his winnings, and the jimber jaw dropped long enough to allow him to remark: "Unless I can make three tricks in spades by the double finesse, game is impossible in that hand. The only way to get a double finesse where I come from is to put the other hand in the lead twice."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now