Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowFlivver Complaint

A Diagnosis of the Intimate Ills of the Family Chariot

FREDERICK LEWIS ALLEN

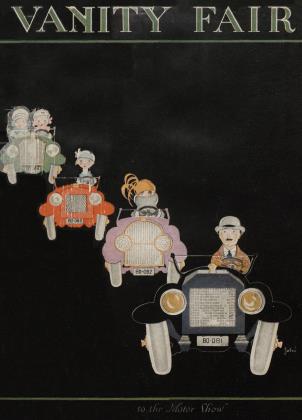

IF you want to see a picture of contentment, watch our flivver coming down the road. A savage squawk of the horn; a sound like the approach of a traveling tinsmith shop; then the little blunt-nosed creature rushes by in a blur, bulging with people. There are so many members of the family in it that they overflow its gunwales. You feel that if you tried to push one member in a little farther, a couple of others would pop out into the road under the pressure. But their faces—there's a study! You may search the flivver in vain for the supercilious nose and world-weary expression of the man who rides in regular automobiles. Every face in our flivver wears a smile of onest rapture. Every face seems to say, We've gone thirty miles already, and if anther nut doesn't drop off we're likely to get ome!" Every face reveals the satisfaction f riding in something that is not a mere autoobile, but that partakes also of the attributes f a gymnasium, a pet, and a bouncing-cart.

You may talk about your regular automoiles, but our flivver has certain individual ualities which set it apart from such as these, ts rattles, for one thing. It is a whole jazz and in itself. A musician could spend a year earning to distinguish between the light, brisk hatter of the lamps, the dull banging of the bolbox, the occasional tinny sound of the muduard, the vibratory note of the loose handle If the emergency brake, the baritone muttering f the palsied horn, and the full orchestral rash as the flivver hits a bump in the road. Whenever you suddenly see the faces of every ccupant of the flivver harden into an exression of anxious attention, you may be sure hat they have suddenly detected a fifty-eighth attle, and are wondering what is going to give: whether the dear old flivver will fall on its ittle snub-nose or just go lame.

Its floor, too, has a quality of its own. It is lot just an ordinary carpeted automobile floor. It is a historical museum, a diary of family adwenture; examine it carefully, and you can reconstruct the past.

A fragment of goldenrod stalk: yesterday we went afield and brought home flowers. A torn bit of newspaper: we keep up with current events. A powder of red clay over all: yesterday the flivver carried home somebody who had been mountain-climbing, and the day before it had rained. A milk-spot on the rug: the flivver calls regularly for the milk at Mrs. Wood's, and this morning it took the old bridge in the hollow just a shade too fast.

An Outline of Maladies

BUT perhaps the most distinctive thing about the flivver is its precarious state of health. It suffers from innumerable ailments. It has a new one practically every day. There isn't a thing in the index of the Home Medical Library that it hasn't been through. Its whole career may be looked upon as a struggle for life. Every garage man within fifty miles has taken its pulse and looked at its tongue as it came gasping feebly into his repair-shop. If you should ever come to call at our house, and find the family all sitting at home in a hush, you would know that their hearts were in White's Garage, where a very sick little flivver lay helpless and silent under the surgeon's monkey-wrench. Oh, I know, it always recovers. The other day it came down with three maladies at once, and we almost gave up hope; but for the sum of one dollar and sixty-five cents the doctors had it on its feet again— temperature normal, pulse strong, ignition regular. It always recovers. But it always has one wheel in the grave.

Its ailments are odd. Some of them, I think, must be peculiar to the species. Here, for example, are a couple of typical ones:

CASE 1. Symptoms:—In the early stages of this ailment, the entire, family may be seen leaning far out over the sides of the car, till the general scene reminds one of a bowl full of drooping flowers. Every ear is flapping, every eye vacant. They are listening. They have heard a new noise. In the later stages, the symptoms are similar, except that one member of the family rides behind on the trunkrack, lost in intensive study of the rear axle. The machine proceeds slowly and with evident pain.

Diagnosis:—It's the differential. Don't try to handle this kind of a case yourself, but make the patient as comfortable as possible and drive it at once to a reputable garage. The differential is very serious. Sometimes it is fatal.

CASE 2. Symptoms:—The flivver simply will not start. No amount of cranking does any good.

Diagnosis:—Fliweritis, or difficulty in starting.

Treatment:—Prime three times, crank five times; prime twice, crank five times; prime once, crank five times; crank five times more, crank five times more, crank five times more, and so on.

Alternative treatment :—Get the whole family out. All together push the flivver to the top of a hill, or rather just beyond the top of a hill. Select the nimblest member of the family. Place this member beside the right front wheel, ready to pull out the primingwhat-you-call-it with the right forefinger. Take off the brake. Let the machine coast down the hill, the nimble one dancing along beside it and pulling out the primer. Throw in the low speed. When the flivver comes to a stop at the bottom of the hill, call the family together again, and push the flivver back to the top of the hill. Repeat, running if possible sufficiently near to the side of the road to force the nimble one to dance through blackberry bushes while priming the engine. Repeat. Repeat again. Repeat once more. Repeat.

Theoretical Diagnosis

THERE are lots more of these ailments. I have been a passenger in the family flivver only two months, and I have learned the names of a lot of them. This is an immense advantage, for it enables me to have a theory to put forward whenever things go wrong. We all have theories to put forward at such times, which makes rather a pleasant game of the thing. Suppose, for example, the flivver gets some sort of a stitch in its side while proceeding at full steam along a sandy road. It begins to hiccup—faintly at first, then with more and more emphasis. We pause for consultation, choosing for the purpose a particularly warm and shadeless bit of road.

"It's the bushings," says Polly. (She learned of them last week, and took a fancy to the word.)

"Well, the wish-bone's gone at last," says Tod.

"Imagine the spark-plug choosing this moment to be taken ill," laments the Old Boy.

"Look at the front wheels, Tod," implores Mother. "I'm sure one of them's loose." (This is an obsession of hers. To put it frankly, she's an alarmist.)

All eyes are turned on me. Rapidly I run over the remnants of flivver vocabulary in my mind. Finally I make my decision known.

"The magneto," I announce, with a wave of the hand.

The flivver's nose is headed for the nearest garage, where a mechanic listens to it for a few seconds, turns off the engine, climbs in headforemost with a wrench, comes out, cranks the engine—and presto! the hiccup is gone. We crowd around him for his verdict.

"A nut dropped out," he says. "Oh, twentyfive cents."

"I knew it from the very beginning," we declare in chorus. We climb in, and wedge ourselves in place. The flivver backs noisily out into the road and chortles off toward home, every one of its fifty-seven rattles in action.

"Wonderful how these little machines stand up, isn't it," muses the Old Boy. "I'm not sure that we need to turn it in this year after all."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now