Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowAt The Sign of the Blue Lantern

A New Series of Limehouse Sketches. IV. Mazurka

THOMAS BURKE

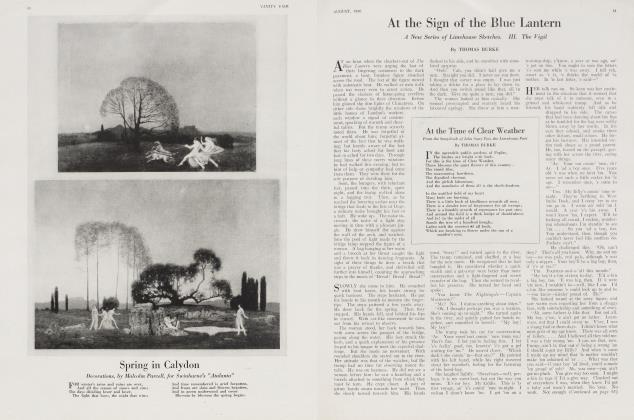

CHRISSIE RAINBOW stood on the balcony of her tenement home, and looked down upon the evening life of Limehouse. In the warm sapphire dusk, even the voiferant dockside lay hushed, expectant; and footsteps crackled like fire-works. Clusters of boys and girls hung at street comers, chatting and softly giggling. Yellow men paired with silent females, and swam into quiet byways. Hard-faced women collared simple

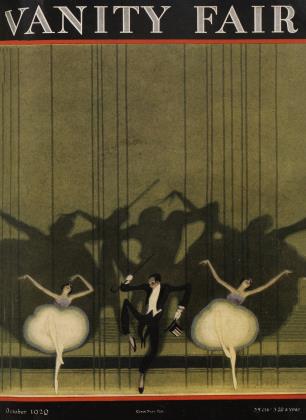

Then the big lamp outside the Blue Lantern was lit, and lights appeared behind its many windows. An organ stopped at its doors, and sprayed the neighbourhood with a rapid fire of rag-time. Its bright summons set young feet a-tapping and old heads a-wagging, and into the gas-lit circle moved flaring hats and wide grinning faces. The great sea of roofs that swept out to Essex began to twinkle with luminous points, and all-night factories made gashes of light across the distant gloom. As the twilight deepened to night the loungers began to pull themselves together and to make certain movements towards substantial entertainment. The two music-halls, shrinking behind their bold veils of light, flung open their doors to a clamant crowd of seekers after mirth. The cinemas were "now showing", vehemently, Lillian Gish and Nazimova.

The organ stopped its ragging. Chrissie heard its rasping wheels bear it away, and, with its passing, the motley murmur of the crowd again vexed her ears with its uneasy calm. For some minutes she stood thus, drawing to herself the breath of the city. Then, from the little Chinese cafe at the corner of King Street, came a sudden burst of music as its latest attraction, a penny-in-the-slot piano, clattered its way through a new record—the Mazurka from Coppelia.

Straight through the open window to her it came, riding joyously, insolently, above the purring street; and it captured the idle half of her mind, and she found herself smiling in welcome of it. The chorus songs of the street and the organ music which had just passed had made her feel at no time any litheness of limb at their rhythms. But here was something novel; charged with colour and various melody, and rippling with lightness of heart and holiday; something strange to her, yet made to her own heart's measure. It carried to her an invitation as flagrant as the nod and beck of a passing reveller at carnival. It disturbed her and set her in effervescence. The tired, purposeless crowd below took on colour for her eyes. And while the saucy, provocative phrases of the Mazurka stirred her heart to petulance, her skin tingled with delight, vibrating to them.

AND, suddenly, she wanted to be out—just out: anywhere with the crowd, touching fingers or brushing shoulders with people, looking into other faces, and mixing and exchanging emotions. It - teased her with its message. Like a caged bird she stood, her breast against the bars of the balcony, her amis outstretched to the great plain of London. Blunt of face, and without colour, she yet held charm in her figure. Sturdy and pliant as a young tree she stood, her frock blown, her limbs rippling to the music, her face rapt. She wanted to throw herself into this London and become one with it and part of it. Twice the mechanical contraption went through the new record, while she stood and longed and bubbled with foolish smiles.

With an impudently triumphant flourish it finished, and she turned slowly away to her room. In the chill half-gloom of the summer night, it looked mean and fusty and bare. She discovered a sudden disgust of it and its petty appointments. She moved about it. She picked up a book, and threw it down. She sat on the edge of the bed. She got up and straightened an ornament on the mantel-shelf. She again took up the book. But her mind was outside: she was listening to the crisp gossip of young feet to the pavement; she was seeing the long Barking Road—all breeze and glare and glitter of lamps and shop-windows; she was seeing the happy encounters of boy and girl; and she felt the odour of lilac floating from the public gardens. The streets were breathing softly, closely, wooing her. The Mazurka still simmered within her.

Until to-night her evenings had followed a changeless routine. Home from the factory —wash—a meal of some tinned food and tea— necessary repairs to garments—then a book of some educational course—and bed. By her fellows at the factory she was voted slow. Miss Stuck-up, was her name there. "Look at the stuck-up going 'ome to keep 'erself pure!" "We ain't good enough for the chaste Stuckup." All their invitations to "evenings" and "crawls", to " 'ave a bit on", she declined; and when, on the pavement outside the factory, the girls stood in chattering groups, to argue the evening's indulgence, she would slip through them and away. To all their gibes she had one reply—an exasperating smile of self-sufficiency.

But to-night she could not rest; she was not company for herself. The benignant dusk, the crooning of the summer evening, and the bright challenge of the Mazurka had entered her blood. Solitude now distressed her. She longed to be in the life that was all about her. She longed to be accepted by the crowd, and to be one of it. And suddenly she rose from the bed, snatched her hat, and adjusted it at a rakish angle. A few deft touches smoothed the poor calico frock; then, with thrilling pulses, she ran down the stone stairs to the street, and surrendered herself to the crowd.

SHE was out. Cleverly she copied the saunter of the other girls: the swinging arms, the swirling frock, the roving eye. In the high charm of her fifteen years she strode. Her thin brown hair flowed about her shoulders, and the swift lines of her limber legs curved aptly from pendulous skirts to natty shoe. She had great joy of the street. She was prepared now to accept all things. She needed not to-night the rarefied atmosphere in which she had hitherto held herself from contact with the mob. She had come down off her perch, and was now warm and fluent.

But the street made no demonstration at her condescension. None looked twice at her. The East End boy looks only for faces; if they be not pretty all other charms are without virtue. She searched here and there for some of her work-fellows. They were certainly "out", amusing themselves somewhere, and it would be pleasant to join them. It would be pleasant to be popular with them: They would perhaps find for her a boy, who would walk with her and take her arm; for she thought that she wanted a boy to walk out with and talk with. Really, she wanted to talk with London and be friends with it.

Up and down the street she strolled, but saw no familiar face, nor any that sought to make itself known. Tiring, after four turns, she went to the Tunnel Gardens; and here she boldly invited with feet and eyes. A few lads looked at her, but with sniggers and ribald comment. These were the knowing ones, who chose carefully. "Pasty-face!" was the welcome she got from them. Other lads looked at her without remark, but these were the bashful, the inexperienced, who did not know how to force an introduction; novices, like herself.

But, at the further gate of the Gardens, she found adventure.

Mr. Sam Ling Lee, in straw hat, brown boots and store suit, was leaning against a railing, twirling a whangee cane. His face was placid, his appearance highly respectable; and he seemed lonely. She came to him and passed him with a flutter of frock, and gave him a long, expressive look. He smiled. Some paces away, she looked back. He was still looking. She stopped at the railings, and smiled. He came to her.

Well, they walked out of the gardens towards Pennyfields. Great elation was hers, and her little lips were-pursed tightly to hold back the smile that would have lodged there. She was living. She had got off. She was no longer to be sneered at as the Stuck-up, the timid. She could cut a dash as well as anyone else. Mr. Sam Ling Lee, too, was proud. A white girl had given him the glad eye, and was coming to Pennyfields to take a cup of tchah, and to eat with him.

Continued on page 122

Continued from page 47

At the Tea-House of the Golden Chrysanthemum, they sat at a marble table; and she drank tea and ate little cakes, and thrilled to his quaint accent and turns of speech. And he leaned across the table and pressed her hand, and she returned the squeeze. And he told her, by many difficult words, that he knew the keeper of the tea-house, and that he knew of a nice quiet room where they could sit and talk. And he would like to sit and talk with her.

So they went to the quiet room.

IT was past public-house closing time when she left it. She stepped into Pennyfields, narrow, dark and deserted, and her light shoes made clear, staccato sounds. She walked dreamily. Her eyes were heavy. But there was a warmth and fulness about her face that was new, and that became her. She carried herself with confidence. The others could no longer swank before her.

Then, as she turned into West India Dock Road, the darkness screamed at her. Snarls and growls and cat-calls met her, and vile words leapt upon her. And suddenly she was surrounded by a dozen of her work-fellows. Too dazed by the attack to speak, she shrank away. But they were on all sides; horrid faces and writhing lips that spat beastly things at her. The full significance of the situation scarcely reached her at the moment. It was an attack; that was all she could clearly understand; and she turned blindly to break through them and run. And, as she turned, one pushed her between the shoulders, and she stumbled against another who pushed her back. Dumb, except for sobs, she waited, terrified, in their midst; and they encircled her with stretched arms and pointed fingers; and she stood breasting a ring of living spears.

And from point to point of the circ'e she was pushed and hustled and bunted like a sack, until she dropped.

Then, clamourously, they indicted her. There's yer quiet ones! There's yer pure work-girl. There's yer Stuckup! Gorn with a Chink! Ugh, the dirty cat! That's all that would 'ave 'er, I suppose.

They let her go, then, and went off in a grinning, giggling mass.

Slowly she crawled to her feet, and slowly she crawled home, numb, sobbing, stricken. It was Spring no more. The scent of flowers was gone. The air was heavy with the religious odour of fried fish. There were no more of colour and revelry and happy streetlife. She looked upon the every-night Limehouse, and saw grey streets, gruff buildings, ragged roofs and walls, tramcars, 'buses, dark pubs., and ugly, dolorous noise. And as she staggered into her room, and collapsed upon her bed, an uglier noise broke forth below, and a damned jingly, hiccuping, penny-inthe-slot piano gibed and reviled her with the Mazurka from Coppttia.

That is how Chrissie Rainbow became a Blue Lantern girL

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now