Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Evolution of Vanity Fair

Part I. The Civil War Period, Under Artemus Ward

JAMES L. FORD

VANITY FAIR, as a paper of light reading and satire, has had many predecessors during the past threequarters of a century. To study them all would give one a clear idea of our national development in appreciation and taste. As far back as 1852, we find a paper called Yankee Notions, which contained cartoons, as well as humorous text and pictures; but cartooning was no new thing in America at that time. Even before the Revolution, cartoons, roughly drawn but effective, had their say in political affairs, and it is a matter of history that in this art Paul Revere was eminently successful. Nor was American humor, racy of the soil, a novelty in 1852, for Benjamin Franklin had set the pace for it at the moment of signing the Declaration in his famous remark, "If we don't hang together, we are quite certain to hang separately."

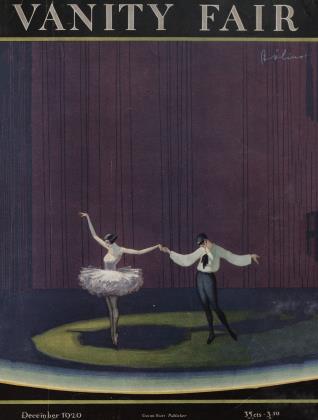

Although Franklin was at this moment helping to rid the country of its political allegiance to Great Britain, he did not succeed in throwing off the shackles of British humour; for the original Vanity Fair, founded in 1859, was modelled after Punch and its page cartoons were printed in exactly the manner that the Punch cartoons have been printed up to the present day, with the reverse side of the page left blank.

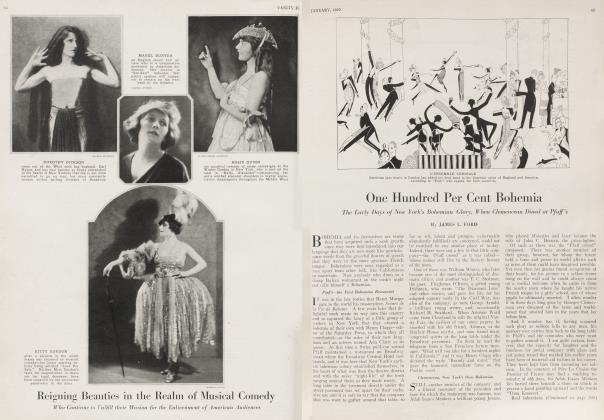

The first number of the first Vanity Fair appeared on the very last day of 1859, and the final one some time in 1863. It was considered a remarkably witty and clever journal, and its list of contributors contained the names of many writers and artists well known in their day, beside one or two whose fame still survives. Among these were R. H. Stoddard and E. Clarence Stedman, George Arnold, FitzJames O'Brien, Augustus Hoppin, Frank Bellew and Charles Dawson Shanley. Richard Grant White was another writer of distinction and Artemus Ward, who came from Cleveland to fill the editorial chair, remained with it to the very end and was wont to say that it died under his hands.

Richard Grant White, the father of the late Stanford White, was a stickler for purity of style and was well known for his satirical writing, notably The New Gospel of Peace, which appeared just after the Civil War, and The Fight in Dame Europa's School, which was published after the Franco-Prussian War. He wrote many paragraphs and editorials for Vanity Fair. Mr. Stedman's poem, The Prince of Wales' Ball was printed in two numbers and added materialy to the renown the author had gained by his Diamond Wedding of an earlier period. Mr. Stoddard contributed much verse and at least one serious story, John Hardy's Christmas Eve. Artemus Ward's contributions include some of his best known work, such as his visit to the Mormons and his criticism on Edwin Forrest as Othello. Augustus Hoppin was one of the best known illustrators of his day and made the pictures for William Allen Butler's Nothing to Wear, a poem that achieved almost sensational success.

New York Sixty Years Ago

PUNCH'S cartoons, reprinted from that famous English periodical, and taken from the work of John Leech and that far better cartoonist, John Tenniel, constitute a political history of Great Britain, during their time, that is of no small value to the student. In a lesser degree, so do the pages of Vanity Fair give one an idea of the subjects most talked of in New York sixty years ago. The HeenanSayres fight excited no inconsiderable comment, mostly adverse, during the sixties and was the subject of one double page cartoon by W. L. Stephens, who did most of the work of this sort for the paper.

Another topic that gave frequent employment to both writers and artists was the visit of the Prince of Wales to New York, and we find one brief paragraph to the effect that the first dance at the Academy of Music Ball was a breakdown, referring to the collapse of the platform on which the distinguished guests were sitting. One poem by an Irishman expresses the hope that, on ascending the throne, the Prince will "remember poor Erin", and the latter did before he became King. We even find, as far back as April, 1860, a reference to the quarrel between Henry Ward Beecher and Theodore Tilton, though it was not until thirteen years later that the charge against the Brooklyn pastor was made public at the Woodhull and Claflin meeting at Cooper Union.

The employment of male clerks in dry goods stores seems to have aroused the animosity of the editor, for there is constant reference to the 'counter jumpers', who are accused of taking the bread out of the mouths of women. A strong anti-English note is evident in many pages and there is one excellent cartoon that shows John Bull, his gouty leg labelled 'national debt' lying back in his chair, with the Emperor Louis Napoleon at his throat and French soldiers in Zouave uniform climbing upon his body. In the background lurks the ghostly figure of the great Napoleon in threatening attitude. The caption is John Bull's Old Nightmare, beneath which is printed this line from King John: "Even this night your breathing shall expire ... if Louis do win the day." In the picture showing a newly arrived Englishman asking the bar-tender for 'a mint julep 'ot', we see the genesis of the famous minstrel joke of a later day: "Whiskey cocktail, sir? Very good, sir. 'Ot or cold, sir?"

What was once termed "servant-galism" is the subject for innumerable jests, most of which are aimed at the newly arrived Irish Biddy, for at this time the prejudice against these immigrants was so strong that the line "no Irish need apply" was common enough in the advertisements calling for domestic servants. The humours of skating in Central Park are touched upon with much frequency and usual!, depict some physical catastrophe endured by the skater. Grey-haired citizens, who recall the time when the so-called 'measuringworms' were a city pest, might be interested in a sketch showing a man with an umbrella, standing under a tree from which a shower of worms was falling.

From the pictures dealing with the visit of the Japanese Envoy we see plainly that the artist had no idea of what these visitors—the first of their race seen in this country—really looked like, for the faces depicted are more nearly negroid than anything else. References to Barnum's What-is-it recall the days when the Museum at Ann Street and Broadway was one of New York's chief objects of interest. The What-is-it was an idiotic coloured boy, discovered by Barnum on Peck Slip and advertised widely as the greatest of all living human curiosities. As a museum exhibit he took equal rank with the cherry-coloured cat, the woolly horse, and the club that killed Captain Cook.

The steamship Great Eastern, at the time the largest vessel afloat, is frequently mentioned. On one page we find its builders sued for infringement of patent by an American inventor, who claimed to have the exclusive right to build ships with both side wheels and screws. Mention of the Elysian Fields will not be understood by the present generation, but some of our elders remember that they were situated in Hoboken and much resorted to by urban pleasure seekers. It was there that the Hoboken Turtle Club held its annual revels and it was in the nearby marshes that the turtles were caught for their feast.

A 'best seller' of the sixties was Rutledge, published anonymously, and notable, not only for its interest but for the fact that the name of its heroine is not once mentioned. Not until some years later was its authorship rightly attributed, after many false guesses, to a Mrs. Harris, a voluminous writer of her day. Vanity Fair prints what purports to be an authentic portrait of this anonymous author in the shape of a woman with a mask over her face.

(Continued on page 116)

(Continued, from page 44)

Newport as a Centre of Culture

THAT Newport was at one time a town of culture rather than of fashion is evident from a description of a drive around that summer capital and the comments of one of the characters. "There goes H. T. Tuckerman! That one next to him is George Boker of Philadelphia. There goes Charlotte Cushman and Miss Stebbins—and Hattie Hosmer's in town, they say. That's Hunt, the artist, and I do believe I just saw Hiram Fuller. Isn't that Mr. Bryant? Yes-Oh, isn't he the very ideal of a fine old bird! Bless my soul, there's Douglas and there's that sweet little thing, Patti—isn't she a darling? I wonder - where little Wilhorst is this summer—I used to see her and the Boucicaults every afternoon almost, down at the Rocks. Do any of you know Madame Le Vert? I declare Brignoli s looking very well. I thought I just saw Anson Burlingame."

It would seem that the editors of Vanity Fair had been denied the gift of political prophecy and discernment, for their treatment of Lincoln, just then emerging from obscurity by reason of his Cooper Union speech, is trivial and almost contemptuous and the cartoon printed at the time of his election merely puerile. They sneer at Wendell Phillips, too, and they evidently have no sympathy with the abolition cause, Now and then we note evidences of the secession movement but, although it lies but a few months in the future, it is not taken very seriously. A similar lack of prophetic gift is shown in a brief paragraph predicting that in 1870 the last omnibus will be superseded by the street cars.

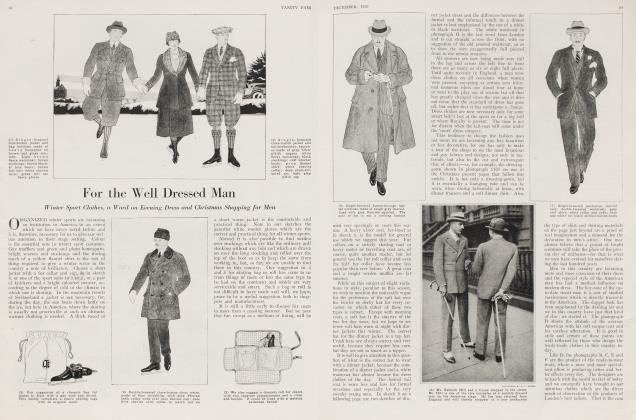

Men's clothes are satired by many of Vanity Fair's artists, but no ridicule is heaped on feminine dress, though the hoopskirts worn at this time offered abundant opportunity to both pen and pencil. It may be, however, that men were more gallant and chivalrous toward women than they are now. And in this connection it may be remarked that the feminine hand does not appear in any of the pictures or the text of the paper, for, at that time, women had not achieved what they call their "economic independence" and took but little part in the work of the world.

To those interested in New York of sixty years ago and in the progress of the city through the succeeding years to the present day, Vanity Fair and its successors in comic journalism offer a

most interesting study. It is especially interesting, also, to compare the present issue of Vanity Fair with one of the older ones bearing the same name, if only to realize the strides made in art, colour work and printing during the intervening period.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now