Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe New Laws of Auction Bridge

And a Special Word on the New Penalty for a Revoke

R. F. FOSTER

THE new code of laws for auction bridge, issued by The Whist Club of New York, has now had time enough to be pretty well tried out by those who follow the strict rules of the game, and the result seems to be eminently satisfactory, the laws being more logically arranged than in the old code.

One excellent feature of the new rules is the extremely complete index that follows the laws themselves. This is intended to enable the parties to any dispute to turn at once to the law or laws covering the point at issue, instead of having to ask some bystander, with more leisure on his hands, to look it up, while the players go on with the rubber. The laws take up 45 pages, and the index 21.

In the Introduction, the Committee specially requests players to pay more attention to the exaction of penalties, and calls attenion to the fact that while the revoke is about the only penalty that is universally insisted on, it is not actually as important, nor as likely to influence the result, as other infractions of the rules which are generally condoned.

There are one or two changes which are of interest more to club members, and those who are in the habit of playing for considerable stakes, than to those who confine themselves to the average social game.

One of the points that has been officially decided by the Committee is that any bets on the winners of the rubber shall be decided in favor of the partners who have the majority of the points, after the scores are balanced, regardless of which side wins two games. Sticklers for the exact use of words have always contended that the rubber meant two games out of three, regardless of their value. For the future, this definition will not apply to auction. In case the points are a tie, the rubber will be a tie, technically.

Another change is in the decision that in drawing cards, no matter for what purpose, any person exposing more than one card shall draw again. Under the old rules, this was done only when cutting for partners; otherwise the higher card of the two exposed was the cut.

One matter, never before even touched upon, is the choice of seats by the opposing partners, after the lowest cut has made his choice, the second lowest cut sitting opposite him. The new rule is that the third lowest cut shall have the choice of the two seats still vacant. There is no provision to the effect that when the cards are spread, the four at each end shall not be drawn, although that limit is still placed on cutting to the dealer. The idea of this limit rule in cutting was to prevent a player from locating an ace toward the end of the pack and drawing it; a trick for which one of the members of a prominent card club was expelled some years ago.

THERE are three laws to which the Committee ask particular attention, urging all classes of players to learn them and to enforce the penalties for their infraction, in order that these may become as generally known and insisted on as the revoke penalty.

The first of these is Law 26d, which imposes a penalty of 25 points in the honour column upon any player who lifts or looks at any of his cards until the deal is complete. This law has been on the books for the past four years, imposing a penalty of 25 points for each card lifted or looked at, but it does not seem to have ever been enforced except in sporadic cases. There is, however, a case on record in which a player was charged 325 points for picking up his hand just before the last card had been dealt.

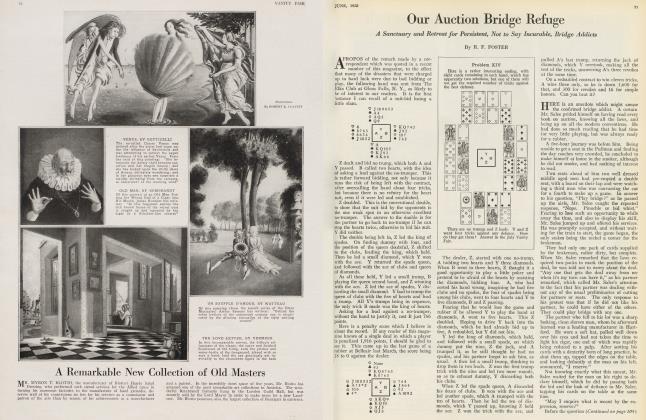

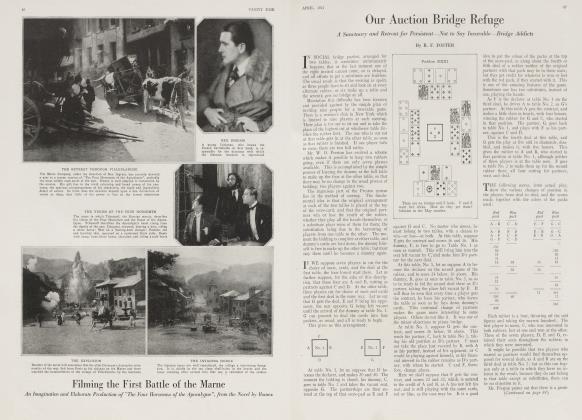

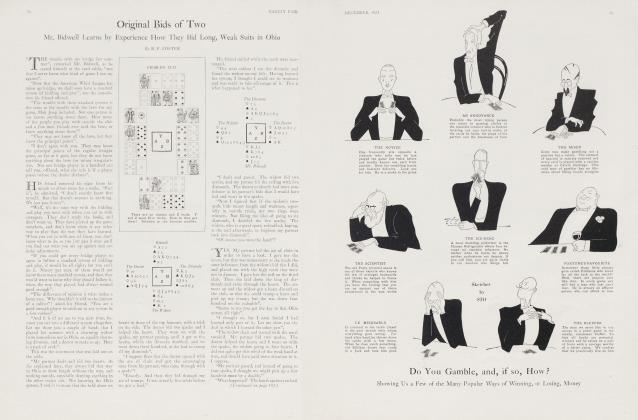

Problem XIX By R. C. MANKOWSKI

Hearts are trumps and Z leads. Y and Z want four tricks. How do they get them? Solution next month.

There being only six cards, this may seem an easy one, but it has more twists to it than a tangled anchor rope.

The Committee admits that this is not as serious an offence as some others, but it is a most annoying habit and likely to result in an exposed card, which necessitates a new deal, and other unfortunate complications.

Another law to which special attention is asked, is No. 53, with regard to naming or touching cards in the dummy. A card from the declarer's hand is not played until actually quitted. As there is no penalty against him for exposing any or all of his cards, he may put it back in his hand and play another. But if he touches or names any card in the dummy, it must be played.' If he touches two or more, he must play one of them. If dummy names or touches a card, it is for the adversaries to decide whether or not that card shall be played.

Law 61e covers a point about which the average player is entirely too careless, and that is looking at tricks already turned down and quitted. The penalty for this offence is 25 points in the honour score, which, if strictly enforced, is calculated to cure some of those who are in the habit of turning up and looking at almost every trick they take in, often without any interest in it whatever.

Probably the most. interesting change is in the revoke penalty, which is now reduced to two tricks, or 50 points, instead of three tricks and 100 points.. The Committee says: "This may work unfairly in the isolated instance in which the revoke benefits its maker, but as, in about ninety-nine cases out of a hundred, the revoke does not do this, the new penalty more nearly fits the offence in the vast majority of cases. In reducing this penalty, the possibility of an intentional revoke is not even contemplated; the laws do not provide a penalty for any form of crooked play. . . . Should a player intentionally revoke, ostracism will be more effective than any penalty the laws could prescribe."

IN commenting on these laws, it is fair to say that they present some curious twists of logic, and are still quite unnecessarily ambiguous. Take Law 53, for instance. The declarer must play any card he touches in the dummy; "unless his touching the card is obviously for the purpose of uncovering a partly hidden one, or to enable him to get at the card he wishes to play". How is one to judge when the intention is obvious? Why not state that in case he is not going to play the card he touches, he shall say, "I arrange", before pushing it aside to get at the card he wants?

We find the same ambiguity in Law 42, which says that if a player bid, double, or redouble and then 'attempt' to change to some other declaration, or to change the size of a sufficient bid, he may be penalized as for a bid out of turn. Unless; "a player who inadvertently says no bid, meaning no trump, or who says, spade, heart, diamond or club, meaning to name another of these, may correct his mistake, provided the next player has not declared." The law then says that 'inadvertently' refers to a slip of the tongue; not a change of mind. How one is to distinguish between the two is not specified. Some persons are very quick thinkers.

With regard to the revoke penalty, it has been pointed out for years that the penalty of three tricks or 100 points is based on nothing pertaining to the game of auction, and has no relation whatever to the offence. It is simply borrowed from the old whist days, when three tricks was considered about enough to prevent a player's revoking on purpose, tricks being worth only a rubber point apiece.

In paring down the penalty, the Committee have simply modified, in a very small degree, one of the most absurd and unjust laws in any game. They admit that for any one to revoke on purpose is unthinkable, and state that it seldom benefits the player in error. (They do not mention the cases, however 'isolated', in which it benefits the opponents.) There are any number of instances in which the revoke not only does not benefit the player in error, but has precisely the contrary effect. As an example, take the following, deal, which came up at the Knickerbocker Whist Club last winter, for the accuracy of which I can vouch, as I was dummy:

(Continued on page 106)

(Continued from page 77)

Z dealt and bid no-trump, A passed and Y called two spades. When B passed, Z went back to no-trumps, which all passed, and A led the queen of diamonds, B putting on the king to unblock, Z playing small. On the return of the diamond, Z played the eight and A won with the ten, leading the jack, on which dummy discarded the five of hearts, B the nine, and Z the trey.

"No diamonds, partner?" demanded dummy. Z shook his head in answer, having sorted his cards with the ace of diamonds next his king of hearts.

Still under the impression that he had no diamonds, Z allowed A to run off the whole suit, discarding from his own hand the seven of hearts, trey and eight of clubs. Having finished with the diamonds, A led the ace of hearts in response to his partner's original encouraging discard, dropped Z's unguarded king, (it was at this point that he discovered that his ace of diamonds had been sorted with his hearts) and allowed B to make two more heart tricks.

These nine tricks not only set the contract for 150, but gave the adversaries 400 for revokes, a total of 550 scored against a hand that is a laydown for three odd and game, if Z wins the first diamond trick with the ace, makes his two spades, and then puts dummy in with the club ace to make the king of spades and return the clubs.

The fundamental fallacy of the revoke penalty at auction, whether it be for three tricks or two, for 100 points or for 50, is that, as long as it carries with it the provision that the side in error can score nothing but honours as held, it is an indefinitely varying penalty for an invariable offence. This is bad legislation in any game, and there is, apparently, no other game in the world where such an illogical and unjust law exists.

It seems a pity that the Committee of The Whist Club had not the courage to take this opportunity to change a law which has always been a blot upon the game of auction, especially when they had before them the excellent example set by the Committee of the American Whist League in framing their code. In that code, it is stipulated that in no case, can the player who revokes be deprived of any tricks won by his side up to the time the revoke occurs. This is sound logic. How can a player have gained anything if he has not yet revoked?

At auction, a player may make a grand slam on the rubber game; but if he is a bit careless on the twelfth trick, and revokes, he not only scores nothing at all toward game, but his adversaries score against him, the penalty in this case amounting to practically 520 points.

Answer to the November Problem

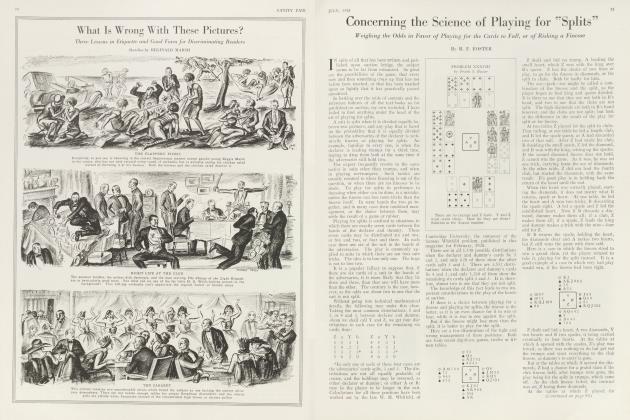

ALTHOUGH R. C. Mankowski set up a pretty straightforward problem in No. XVIII, there were enough traps in it to keep the solver guessing for a space. Here is the distribution:

Hearts are trumps and Z leads. Y and Z want all the tricks. This is how they get them:

Z opens with a trump, and Y wins whatever card A plays. Y then leads the ace of diamonds, upon which Z discards the king of clubs. This allows

Y to lead a club, which Z can trump, covering B's trump if necessary. Z leads another trump, and again Y wins. When

Y leads the last trump, if B has one left, Z discards a small spade.

The next lead from Y's hand depends upon A's discard, as that player must either unguard the spades, or make a small card in diamonds or clubs good in Y's hand, which will enable Y to force another discard.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now