Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowChester Merriwell At Yale

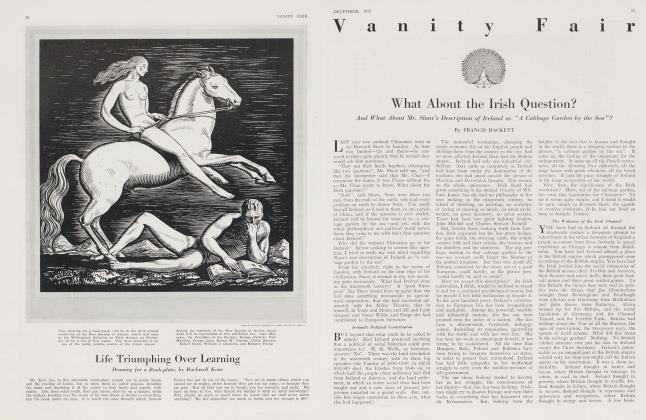

A Fable Taking Cognizance of Certain Curious Changes in Two of Our Leading Colleges

DONALD OGDEN STEWART

THE sound of a trunk being dragged across the floor of Chester's room overhead roused old mother Merriwell from her doze in front of the fireplace. She gave a slight shiver—perhaps from the early morning chill of autumn—and pulled her shawl more closely around her, before resuming a meditative contemplation of the smouldering pine logs.

It was Chester's trunk that was being dragged on the floor overhead, and to-day Chester was leaving home to go away to Yale, or New Haven, as Frank and Dick always called it. Mother Merriwell sighed and her memory reverted twelve years to that 1908 September when Frank, the oldest of the three brothers, had gone to Yale.

She had never quite understood what had happened to Frank at New Haven. She knew that he had "made good"—whatever that might mean—and that he had come home after four years with a trunkful of pictures of his teams and his clubs. Her mother heart had been proud of the boy's success; but it had been quite a blow to discover, after Frank had graduated, that his mind was gone, or rather that, in the twenty-three-year-old body, there was still the undeveloped brain of the boy who, at the age of eighteen, had gone away to be educated.

She had not been sure at first—not until Dick had followed Frank to Yale and had returned with even more pictures of clubs and teams and even less education. Poor little Dick—he had never been very strong mentally, anyway. A tear coursed down the old mother's wrinkled face as she thought of what four years of complete disuse had done to her boy's mind.

Bingo and His Prejudices

TIME, the Healer, had gradually dulled the edge of the mother's grief. No one else had seemed to notice anything peculiar about the boys; as a matter of fact, both had gone ahead remarkably fast in the business world. As a bond salesman Frank had apparently found his college training invaluable; his pleasing personality, his many friends, his ability to impress strangers—all these acquired characteristics had carried him rapidly toward the top. Dick had done no less well in the insurance business. Both were married, happy and successful.

It was a queer world.

Mother Merriwell glanced around the room at the material evidences of her boys' success— the player-piano (how she hated ragtime!)— the many rows of handsomely bound "sets" which had taken the place of her husband's dog-eared classics. Poor Edmund—he had so loved those old books—his Homer, his Catullus.

Her glance fell on a row of red bound volumes—ah, there was Frank's unused set of Tennyson—and, beside it, was his untouched Browning—and below was Dick's set of Tennyson and Browning. In four more years there would be another set of each—and perhaps another successful bond salesman—or possibly a banker this time. Mother Merriwell picked up a dust cloth and started for the book cases. Before she had gotten half way, a low menacing growl made her stop.

"Lie down, Bingo!" she said, with a mixture of fear and exasperation in her voice.

Bingo was Frank's white bulldog, with the deep chest, undershot jaw, and all the other traditional bulldog qualities, including the complete absence of any intelligence. Mother Merriwell and Bingo had never been good friends; perhaps it was because she had one day caught him savagely chewing to pieces one of her husband's favourite books. Literature, curiously enough, seemed to be one of Bingo's fiercest antipathies; Harvard was the other. Frank had taught him, as a puppy, to bark fiercely whenever the word "Harvard" was mentioned; the habit had grown with age, so that now, to say to Bingo "There goes a Harvard man" was to subject the unsuspecting passerby to a savage unreasoning attack of canine fury.

His other trick—that of chewing books to bits—had been somewhat curbed; but the complex—if dogs have such things—had simply been diverted into another channel and now took the curious form of a churlish guardianship of the book cases—an unbenevolent paternalism which forbade anybody to touch a single volume. Bingo hated books and everything connected with them; it was this hatred to which old mother Merriwell ran counter when she advanced toward the shelves.

"Lie down, Bingo!" she repeated, but the dog's only answer was a louder growl.

At that moment the front door slammed.

"Hello there, mother"—this from a tall, broad-shouldered man, with black hair parted neatly in the middle and the rugged look and healthy coat of tan which comes with a hard summer of selling bonds on the golf links.

Bingo greeted the newcomer enthusiastically, but mother Merriwell hesitated. Since Frank and Dick had been at Yale it had become increasingly difficult for her to tell them apart. The same clothes, the same collars, the same way of wearing their hats—old mother Merriwell hated this sartorial reduction to type, and sometimes she dreamed a beautiful dream in which she was alone in a small room with a stout umbrella and one—sometimes two—of the Brooks Brothers.

"Good morning, Dick", she finally ventured.

"Why mother—it isn't Dick—it's Frank. Dick's upstairs helping Chet with his trunk. Here they come now". And Frank hurried to help them.

When the baggage had been successfully deposited on the side porch, the Merriwell family gathered around the fireplace for the last farewells.

"Chet", said Frank, lighting his pipe and stroking Bingo lovingly with his foot, "I certainly envy you. You've got four wonderful years ahead—four of the happiest years of your life".

"You bet you have", affirmed Dick, patting his nineteen-year-old brother on the back.

Chester clinched his fists eagerly. "I only hope I can do as well as you two did", he said.

"That's the spirit, Chet", answered Dick. "We know you can".

Frank looked at his watch. "It's train time, fellows", he said. "Let's go". He went outside to start the motor.

The farewells were said, the sound of Frank's automobile died away in the distance; another Merriwell had gone to New Haven.

Bingo, lying in front of the fire, stirred uneasily.

Bingo Greets Cousin Scofield

THREE months after their brother's departure, Frank, Dick and Bingo were sitting in the living room of the Merriwell homestead —or, rather, Dick was sitting before the fire, with Bingo at his feet, while Frank paced restlessly up and down the length of the room. He stopped for a moment.

"Well, anyway", he said, Chester will be here in a few minutes. We can tell pretty well by watching him during this vacation just what has happened".

Dick shrugged his shoulders. "Something's certainly wrong", he said. "When you and I were at New Haven, did anybody ever stop off in New York on their way home because they wanted to hear—to hear"—lie glanced at {he recently arrived letter from Chester which lie held in his hand—"the Philharmonic play the Pathetique. Now what the devil does Chet mean by that?"

"The Philharmonic is an orchestra", said Frank uneasily. "Alice and I had to be guarantors for their local visit once, but I didn't have to go to the concert", he added. "I'm sure it was an orchestra, a symphony orchestra".

"A symphony concert", groaned Dick. "Oh Lord. I tell you, Frank, I'd say Chet was lying—if it hadn't been for all those—those other strange things he's written home recently —those fellows he seems to be Intimate with— those birds that sit around talking about poetry and literature while they are drinking tea.

"I don't believe it", shouted Frank, his nerves suddenly giving way. "A Yale man might talk about literature, but he wouldn't drink tea, and you know it".

"Yes—but", persisted Dick. "How about those football defeats? Doesn't that prove that something's wrong with the college? Yale men discussing literature; Harvard winning football games".

"Dick", said the oldest Merriwell, and in his eyes shone that same fire that the Harvard team had observed just before he tore through their line for three touchdowns^—"Dick—Yale is Yale". There was silence for a moment; then he added, significantly, "And Yale men are Yale men".

"By God, Frank, you're right!" and Dick clasped his brother's hand with a look which only Yale men would understand. At that moment Mother Merriwell entered the room.

"Frank—Dick", she said. "Here comes the station taxi"—

An automobile drove up outside; a minute later the front door opened and in the hallway appeared two young men.

One of these was Chester; the other might have been Jack Dempsey, except that Jack is always rather well dressed and never wears red neckties.

"Hello, mother!" cried Chester. "Hello, Frank and Dick".

"Chester, my boy", cried the happy old mother running forward to embrace her son. "Hello, Chet, old boy", said Frank and Dick together. "You probably don't know who this is, do you?" said Chester, dragging the rugged, deepchested stranger forward. "It's Cousin Scofield from out west in Ohio. He was going to spend his vacation in New York, but I persuaded him to come up here to us for a while. Cousin Scofield, this is my mother—and my brothers, Frank and Dick".

(Continued on page 102)

(Continued, from page 43)

"Pleased to know you", mumbled Cousin Scofield in a deep voice. When Frank and Dick stepped forward to shake his hand they felt their own fingers closed in a grip of iron. It was a man's hand shake, and though both brothers winced, they felt a greatly increased respect for their western cousin.

This respect increased by leaps and bounds when, a little later, they were seated alone with him on the living room lounge, Chester and his mother having gone upstairs to unpack the boy's bags.

"And how's everything at college?" asked Frank, hesitating somewhat at bringing up the subject which had been troubling him since Chester's unbelievable letters from New Haven, and yet reassured by Cousin Scofield's evident manliness. If there were still men like that at Yale, all was not lost.

"Fine", answered Scofield. "Great. We're going to have a knockout crew —the baseball prospects are first class —and it looks like a big year for track".

"Great stuff!" cried Dick with a sigh of relief. "You know, Scofield, Frank and I sort of got the impression that all that the fellows did at college nowadays was to read poetry and drink tea".

Cousin Scofield laughed uproariously at this. "That's a good one", he said. "Why say, if any bird was caught with a book of poetry, they'd kid him out of college. We're too busy with athletics and our college activities to bother much about classroom work or literature".

At this, Bingo, who had at first held somewhat aloof from the stranger, barked joyously, leaped up into Cousin Scofield's lap, and attempted to lick his face in a frenzy of canine friendliness.

"Down, Bingo", laughed Frank. "Down, old dog. Well, Dick, the old college doesn't seem to have changed any, after all, does it? That's quite a compliment, by the way, that Bingo has just paid you, Scofield. He's suspicious of strangers, especially if he thinks they are Har—

"Cousin Scofield", interrupted Chester, suddenly entering the room with his arm full of books. "Mother wants to show you where your bathroom is. She's up in your room now—at the head of the stairs".

"Come on back when she gets through with you, 'Scofe', old man", said Frank, as their guest got up from the lounge and left the room, followed by an enthusiastic Bingo.

Chester dropped his books on the table and began sorting over the volumes.

"There's a man", said Dick, when Cousin Scofield had disappeared.

"A man's man", replied Frank, and he added, as the final word on the subject, "A Yale Man".

"Do you know 'Marius'?" asked Chester, handing his brother a book from his pile.

"If he's anything like Scofield, I'd like to know him". This from Frank, with a note of deadly earnestness in his voice.

Chester laughed. "Why no", he replied, "he's not. 'He's' a book—Marius the Epicurean, best thing Walter Pater ever did. And here's old Flaubert— say, Frank, there was a man—" and he handed him another volume.

"Look here, Chet", said his brother, throwing Madame Bovary angrily into the fireplace. "I don't know what's got into you since you went to Yale, but it's certainly time you came back to earth. I couldn't believe my eyes when I read your letters. What did you mean by 'last night we sat up till 3 A. M. bickering about realism'—'this afternoon I am going to a lecture at the Art School'—listen, Chet—I'm going to be frank with you, and talk about something I wouldn't ordinarily care to discuss. But you know what senior societies mean at Yale—and you know that Dick and I would hate like the devil to have our brother be the first Merriwell who missed out. Can't you see, old man, that if you get mixed up with literature instead of the important things, you're spoiling your chances? Art and poetry are all right in their place—but we don't want you to ruin yourself, because one or two of these queer birds have got hold of you and are filling you full of aesthetic bunk. See, Chet, old man?"—and Frank patted his brother on the back.

Chester was silent for a moment. "Frank", he finally said, "you're all wrong". And he smiled. "Nobody wants to make a senior society more than your little brother Chester, and", he added, "nobody in my class has, to date, a better chance. Because why? Because, Frank, culture is-the only dope now, at Yale. The twenty-five most cultured men in the class are sure to be elected to a society—and the next twenty have a far better chance than any athlete. And when I left for this vacation", he concluded, "I was on many lists as the fifth most cultured in the Freshman class, and I believe I can stand third by the end of the year. Why do you suppose I stopped off in New York to hear that symphony concert? Because I liked music? I should say not—I hate it. But think of the effect of a casual mention of the Pathetique when upper classmen are around. No, Frank, I appreciate your feelings, but the college has changed since your day".

"But—but", gasped the bewildered brothers, "how about what Cousin Scofield told us. He said that athletics were still the big thing at college".

"Cousin Scofield?" laughed Chet. "Why, I thought you knew that Cousin Scofield was a senior at Harvard".

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now