Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowGeorges and Jack

The Coming Battle Between the World's Most Spirited Boxers

HEYWOOD BROUN

WHEN there comes into the prize ring a man moulded to the heart's desire of every sculptor, it happens only too often that some stumpy person swings a right hand blow and knocks him out.

Fitzsimmons, Jeffries, Sharkey, not one of these great fighters was a museum piece. Bombardier Wells, on the contrary, was as fine a bit of modelling as ever pulled on a boxing glove, but the puffy A1 Palzer and the squarerigged Frank Moran hit him hard and he fell, chipped and marred like an Elgin marble.

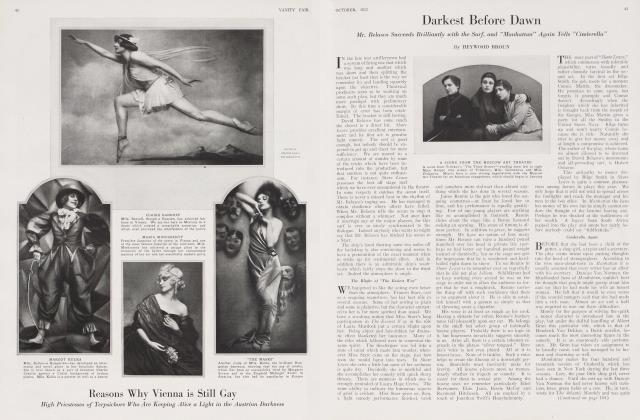

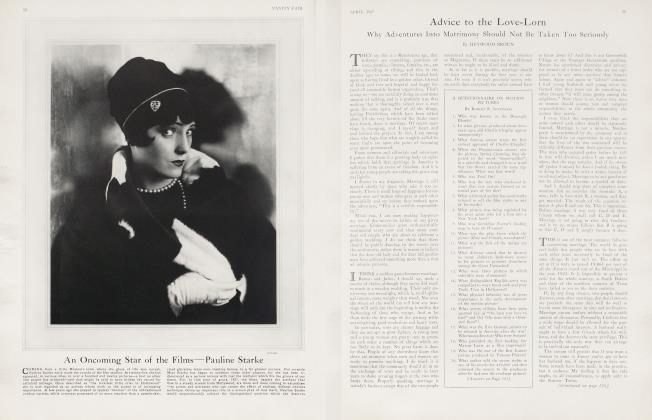

Today, however, there is a strong probability that at last the championship may come to a man who combines the ideal lines of pure art and the strength and stamina demanded by the more utilitarian requirements of professional prize fighting. The issue lies between Jack Dempsey, the present holder of the world's title, and Georges Carpentier, the challenger, who are to meet in some city, as yet undecided, within the next six or eight months.

It is not quite fair to suggest that this is to be a fight between the reincarnation of the discus thrower and the beetling-browed young man from a cave. Dempsey has aesthetic qualifications as well as a mighty right. There is in him a marvellous co-ordination of power and speed. Weighing, at his last fight, only one hundred and eighty-eight pounds, he has fought his way through, and over, the mere mountains of the ring, men like Jess Willard and Carl Morris. And yet, from every sentimental point of view, a victory for Carpentier is demanded.

The Advent of Carpentier

THE young Frenchman is a clean, hard fighter and a very gallant adventurer. He is eminently fitted to stand as a type of the new France, which is turning with increasing admiration and interest to physical prowess. For half a century American humorous weeklies and musical comedies have been building up the notion that a Frenchman is a little person with a black mustache who is much given to gestures and fits of excited anger, in which he invariably attacks his adversary by kicking at him. Curiously enough, the war did little to dissipate this tradition in America. Verdun was not enough to wipe away the illusion. Since then, some little propaganda of a different sort has been effective to a limited extent. Last October Georges Carpentier, Frenchman, fought the light heavyweight champion of the United States, a stalwart native son named Battling Levinsky, and, in the fourth round, Carpentier hit Levinsky in the throat and the American did not get up until many minutes later.

It will be difficult for Americans not to root for Carpentier when he meets Dempsey. The whole story of his ring career is persuasively romantic. Some years ago, when he was a lad in Lens, a slender little fellow just up from a mine pit, he chanced to stop in the street to watch a performance by a travelling showman named Deschamps. This itinerant entertainer took white rabbits from a high hat, hypnotized volunteers from the audience and, as the climax of the evening, boxed a few rounds with an assistant. Carpentier had never seen the sport before and was fascinated. After the show he went around and persuaded Deschamps to teach him. He seemed an unlikely recruit, for he was a bean pole and not a very tall one. His weight was about one hundred pounds.

There was something, however, about the intensity of his earnestness which attracted Deschamps and he took him on. Soon he was a part of the show. A little later he was meeting professional opponents in the ring, although he was still a boy. He fought first as a bantam, then as a featherweight, and so on up through the various classes. His fighting weight today is about one hundred and seventy-seven pounds.

In the process of growing up and fighting up at the same time, Carpentier encountered several reverses, for he was always eager to box the best men available and he met such well-known American fighters as Billy Papke, Dixie Kid, Joe Jeanette, and Frank Klaus, while he was still a novice.

Just before the war, he seemed about to come into his own, for he followed up a knockout against Bombardier Wells with a technical victory over Gunboat Smith, who was then one of the best of the American heavyweights. Carpentier served gallantly in the war as an aviator and was decorated for his share in a dangerous night-bombing expedition to Metz. It was generally supposed that he would never be able to reach top form as a boxer again, after an absence of four years from the ring. Soon after the peace he met some second rate opponent with entire satisfaction to himself and later knocked out Joe Beckett, the champion of England, in a few seconds. Coming to America, he was matched with Levinsky and won in four rounds.

The next step is Dempsey.

It is only natural that a Carpentier legend should have grown out of so adventurous a career. There are those today who will tell you that he owes all his success to Deschamps, his discoverer, who is still his manager.

The story is that Deschamps, the hypnotist, sits in Carpentier's corner in every fight and that just before the bell rings he stares at the opponent of his protege until he is completely under control. The bell rings. The hypnotized boxer advances to the centre of the ring, obligingly drops his hands, thrusts out his jaw so that Carpentier can hit him conveniently— and the thing is done.

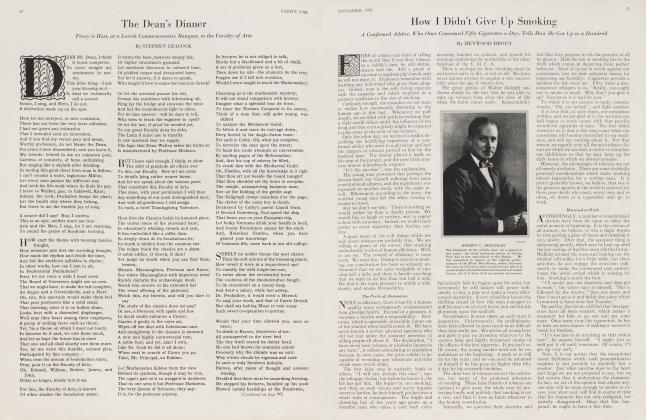

The Career of Dempsey

THERE is more difficulty in making Dempsey a romantic figure, though his rise from obscurity to fighting fame has been rapid. A tramp, he rode from town to town upon the brake-beams and made a little money now and then by meeting third rate pugilists. His early record is not convincing. He was knocked out in a round by Jim Flynn, but it must be admitted that this was a suspicious fight, for only a few months later the men met again and this time Dempsey won in a round. Suddenly, Dempsey discovered a knockout punch. It would be interesting to know whether he found a new trick of some sort or whether a flash of confidence leaped out of the sky and

struck him. A distinguished series of successes opened before him. One after another, he toppled opponents until he met the champion, Jess Willard, at Toledo on July 4, 1919, and knocked him out in the third round. He knocked his huge opponent down seven times in the first round.

I saw both Dempsey and Carpentier in their most recent bouts, and Carpentier was much more impressive. Levinsky, who opposed the Frenchman, did not make a satisfactory showing, but it seemed to me a little unfair for the New York sporting writers to assail Carpentier for the ineptitude of his opponent. Levinsky has a good record and seemed a logical contender. As a matter of fact, I am inclined to think he seemed bad because of the superlative skill of Carpentier. The Frenchman hit him desperately hard in the first round and it is small wonder that thereafter Levinsky never began an attack, but only held on for dear life. The most impressive thing about Carpentier is his speed, both in footwork and hitting. He is an inspired hitter. A blow from his fist lands almost before the spectator realizes that it was started. Even the other fighter is apt to be. a little hazy as to what has happened. He only knows that it is terrible. There was a complete finality about the knockout delivered by Carpentier. To Levinsky, ten was nothing but a number in a procession which might have been infinite. It was fortunate for him that Gabriel did not happen to pick that moment to blow his trumpet. Levinsky would have been compelled to lie where he was and remain unjudged.

Dempsey and Brennan

THE fight between Dempsey and Brennan was quite different. Brennan and Levinsky may be regarded as fighters of about equal skill. They have met three times. Twice the result was a draw, but the last time Levinsky won on points.

Brennan, a good honest second-rater, began his bout with Dempsey very cautiously, but, before the first round had ended, he discovered that Dempsey could not annihilate him with a single punch. More than that, he found that he could hit Dempsey, and he did. Again and again the none too skilful, though courageous, Brennan thrust out his left hand, and again and again Dempsey's nose was there to meet it. Brennan also scored several times with right hand uppercuts. His right hand swings were less effective, for, though three or four landed, Dempsey was successful in rolling his head back a little so that the blows did not come with full force. Nevertheless, one of these glancing right hand swings of Brennan's cut the champion's ear and Dempsey bled. This is high disgrace for a champion and we noticed that when Dempsey left the ring he took pains to wrap a towel around his head so that the spectators at the Garden, who must be passed at close range, could not see the extent of his injury.

To digress a little, it may be remarked that in the excitement of a bout, blood is not apt to make even the novice among fight-goers squeamish. The young woman who sat in front of us at Madison Square Garden confided to her escort that she was enormously thrilled at the opportunity of seeing a real prize fight, but that she did hope it would not be brutal. Some rounds later, when the first red trickle appeared upon the cheek of the champion, the young woman seized her escort by the arm and cried out rapturously: "Look we've got his ear." But there was reason and justification for excitement. Another superman had been scratched—and he was no god, but a man.

(Continued on page 98)

(Continued, from page 35)

Dempsey won against Brennan by gradually wearing his opponent down. As a matter of fact, Brennan actually fought himself out. His condition was not so good as that of Dempsey. The strain told. In the twelfth round a blow of the champion's to the stomach hurt him and made him bend over, whereupon Dempsey chopped him over the back of the neck with a right hand punch and sent him down. It was not a pretty blow and, in both England and Australia, it is barred as foul. Our rules allow it and it sufficed, but we must add that Brennan was almost up again at the count of ten.

Carpentier is certainly faster on his feet than Dempsey. I think he can hit harder, although it may be that the champion had an exceptionally bad night against Brennan. At any rate, Carpentier is much more workmanlike. Dempsey is an excitable Anglo-Saxon, while Carpentier is a cool and calculating Latin. In his ring manoeuvres there is none of the aimless fluttering and crouching and sudden retreating which marked the work of Dempsey against Brennan. Dempsey seemed surly enough, as the fight went against him, and there were blazes of bad temper, temper bad enough to make him adopt foul tactics on one or two occasions, but he never showed any emotion as dignified as fury.

Carpentier, on the other hand, although he seems refined beyond primitive emotions, attains in the middle of a fight, a terrifying fury. Still, it is not altogether primitive. It is ice cold. This sureness and confidence will be among Carpentier's best assets when the big fight occurs. Dempsey's confidence has been shaken by his last fight. It required several years for him to gain it and it seems questionable if he will ever be so sure of himself again. Of course, the punishing power of his right hand may again be there, but, as we picture the contest, it will be a meeting between a marvellously fast and selfcontained man, with a rapier, and an angry, surly foe with a mace.

I fancy the rapier against the mace.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now