Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Girl at Nolan's

Showing the Penalty, in Ireland, for Walking with a Soldier

LENNOX ROBINSON

HER day began early. At six o'clock Mrs. Nolan's alarm clock "went off"— as she called it—and she got up, went into Nora's room and poked and pushed her until she woke her. This done, she turned and went back to her bed.

Awakened at last, the great heavy girl dragged herself out of bed with difficulty. She slept in a small oddly-shaped room under the stairs, windowless except for two panes of glass high up near the ceiling, which allowed a little light from the bar to trickle in. After the night, the atmosphere was heavy and fetid and Nora regained consciousness slowly. She slept as she ate—with enormous, unfailing appetite. Her clothes lay in a shapeless heap on a chair and when, without washing face or hands, she had listlessly put them on they seemed hardly less shapeless than before. She twisted her hair into a ball at the back of her head and fastened it loosely with a couple of thick bone hairpins.

Her first duty was to sweep out the hotel bar. Her brush gathered the burnt matches, the cigarette ends, the flakes of dried mud into a heap and spread the pools of spit and the splashes of porter into dark smudges on the tiles. She then washed the counter and the floor.

After the bar was finished there were piles of glasses and crockery to be washed. She washed them in water which was never quite hot enough and which seemed to grow greasy at once and she dried them with a cloth that was never quite clean or quite dry. Then there were bed-room slops to be emptied, floors to be scrubbed, stairs to be scrubbed. A bucket of greasy water and a grey cloth seemed to be part of her, she was futilely engaged all day with their help in making dirty things a little less dirty but never quite clean. When you went upstairs her bucket was sure to be standing on a step; if you went into your bedroom she would sidle out, a wet rag in her hand. Instinctively you recoiled from her, instinctively you avoided looking at a thing so empty of interest, so grey, so greasy, so clumsy and uninviting.

NO ONE, however, was unkind to her. It was true that she was a workhouse child, but her parents had been poor, respectable people who had been swept away by fever, leaving her entirely alone in the world. Mrs. Nolan was kind to her in a careless way. Nora worked hard and if she ate largely she wasn't grudged immense helpings of bacon and cabbage. Her unattractiveness was actually an asset. "I'd rather have an ugly gamawk of a girl like Nora," Mrs. Nolan was heard to say, "than one of those flighty lasses that you'd never know what they'd be up to and the men in the bar would be codding and'going on with."

Certainly no man who visited the hotel bar ever wasted his time in codding Nora. Miss Liston, who presided over that department of the hotel, provided sufficient interest and charm. She was far from being flighty,, on the contrary she was most respectable and very pretty and always very well dressed. The customers called her "Miss Liston", and it was only one or two older men, friends of her father, who ventured to call her "Annie". She had a gift of smart repartee and sharp, rather cruel humour which won her a large crowd of respectful admirers. From time to time during the evening Nora would pass in and out of the bar to fetch clean glasses or to wipe the counter. Her presence was entirely unnoticed and the talk and laughter continued without interruption.

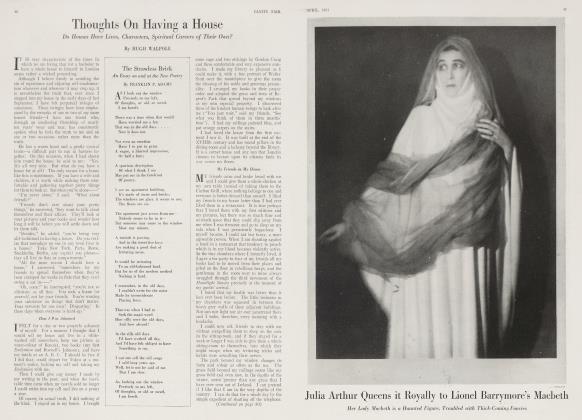

Lennox Robinson, the author of this story, is a young Irish dramatist, who has recently scored a great success in London with his comedy, The White-Headed Boy. The Lost Leader, another of his plays, was produced in New York not long ago. Mr. St. John Ervine regards him as "easily the most skilful dramatist the Irish theatre has produced."

And then one evening Mrs. Nolan heard a sound of sobbing and went into Nora's room and found her lying on her bed crying.

"What's the matter? What is it, in the name of God?"

Nora lifted her head.

"Holy Mother of God," said Mrs. Nolan, "what happened to your hair?"

The story came out gradually. She had been walking with a soldier, it seemed, and the lads had caught her and cut her hair as a punishment.

Mrs. Nolan's political views were not strong.

"Bringing disgrace on the Hotel like this," was all she said. "You weren't much to look at before, but you're a fright altogether now. Wait till I tell Francey."

Her husband was indignant at the outrage.

"A quiet girl like Nora, they had no right to do the like of it. Why wouldn't she walk with a soldier? 'Tis the first boy I ever heard of her going out with." And then he added thoughtfully, "Them English must have a queer taste in women to say they'd go with Nora."

"Sure, don't you know there's not a decent girl in the town will be seen with one of them?" his wife retorted.

"That's true. Wait till I tell it in the Bar."

The men in the bar were a little slow in seeing the joke. Many of them were quite unconscious of Nora's existence. "What girl? .... a lumpy girl? .... I don't ever remember seeing her . . . ." Finally Miss Liston interposed, "I'll show her to you," she said, and summoned Nora to the bar in her sharpest tone.

Seeing her before them, cropped head and all, the joke broke on the bar with irresistible force. That that should have an English Tommy for her boy! They all took their tone from Miss Liston, they were' merciless, there was a ceaseless fusillade of question, of innuendo.

NORA said little in explanation or defence, but gradually the truth came out. It had been under the trees up Church Lane, his arm had been round her . ... he might have kissed her, she wouldn't be sure ... the lads jumped over the hedge, the soldier ran away . . . they had their faces blacked, she wouldn't know them again . . .she knew the soldier well, she had been meeting him for the past month ever since the soldiers had been quartered in the Courthouse.

The little town seethed with the story. It was the first occurrence of the kind in the neighbourhood. Every evening now the bar was crowded and strangers to the town were invited by their friends to "have a drink at Nolan's and see the girl who had her hair bobbed for walking with a soldier." Men who had never noticed Nora before looked at her now: for all her lumpishness there must, after all, be some attraction in her, her size in itself might be the allure and they spoke to her and tried to draw her out, spoke to her not always quite respectfully; not, for instance, as they were accustomed to speak to Miss Liston, but then you could venture to be a little broad with a soldier's girl and one who had been roughly handled into the bargain.

To all this Nora responded but little. Sometimes, at some especially daring sally, a great smile would spread over her red face, but generally it remained stolid, as expressionless as ever.

BUT a week later, just after she had gone to bed, Annie Liston came to her room seeking a pair of scissors. It couldn't be found easily and Nora, lying in bed, in a sleepy voice directed her to look here and there. Annie gave a sharp exclamation.

"Well, I declare to goodness!"

"Have you found it?"

"I have not. I've found something else." She had pulled out an old cardboard box from under a pile of clothes. The scissors were in it. The box was full of dirty hair. "What on earth is this?"

Nora didn't answer. She stared dumbly at Annie.

"You told the men in the bar that the lads carried off your hair. Was it a lie? . . . Why did you bring it up here? . . . Who cut your hair? ... I believe you cut it yourself. Was it all a story you made up?" No answer from the bed.

"I'll go find Mrs. Nolan. .This will be a great tale for them all."

The heavy body raised itself.

"Don't, Annie, don't for the love of God. Look, if you do, I'll kill myself. I declare to God I will. I'll throw myself in the river." "What are you talking about?"

"I will, I will, I'll drown myself."

"You're mad."

"Leave me alone, can't you," Nora sobbed. "Where was the harm in it, it was my own hair."

"And was there no soldier in it at all? Will you answer me, Nora? Was it all a make-up?" "It was."

"But why? Why in the name of goodness would you put out that story of yourself and cut off your hair as well?" .

"'Tis easy for you to talk. There's men always after you and boys killing each other to take you to the pictures. Not a one ever looked at me, and Mrs. Nolan going on saying 'twas a mercy I was such a fright the way I'd have nothing to take my mind from my work."

Continued, on page 90

Continued from page 52

Annie burst into laughter.

"So you wanted a man for yourself and to prove the truth of the tale cut off your hair! Well, I never heard the like of it. And, anyway, I'd rather have the men not see me at all than have them joking and jeering the way they are at yourself."

"They're doing more than laugh at me?"

"What do you mean?"

The big girl didn't answer at once.

"Tis Mossy," she said at last. "Mossy Burke. In the passage behind the bar. He gave me a squeeze. He's going to meet me one of these evenings and take me for a walk."

"I wouldn't doubt him. Nora, let you have nothing to do with Mossy. Don't we all know the sort he is. Look at the way he treated the McCarthy girl. She had to leave the town."

"He's years coming to the bar and he never before looked at me."

"You like to have him after you?"

Nora made no answer, but turned away and buried her cropped tousled head in the pillow. Annie stared at her silently, her shallow laughter suddenly quenched. Was it possible that this uncouth, ugly creature craved—like herself—for admiration and love? And, if so, wasn't the worst that Mossy Burke and his sort could do to her better than nothing, better than utter blankness, better than an eternal attachment to her bucket and her greasy rag? A wave of pity swept over her.

"God help us all," she muttered, and to her astonishment found she had knelt by the bed and caught and clasped Nora's red, work-deformed hand.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now