Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Cosmic "Kid" And Less Serious Drama

Charlie Chaplin Shows the Eloquence of Silence and Laura Hope Crewes Says Much with the Needle

HEYWOOD BROUN

EVERY little while some critic or other begins to dance about with all the excitement of a lonely watcher on a peak in Darien and to shout, as he dances, that Charlie Chaplin is a great actor. The grass on that peak is now crushed under foot. Harvey O'Higgins has danced there and Mrs. Fiske and many another, but still the critics rush in. Of course, a critic is almost invariably gifted with the ability not to see or hear what any other commentator but himself writes about anything, but there is more than this to account for the fact that so many persons undertake to discover Chaplin. As in the case of all great artists, he is able to convey the impression, always, of doing a thing not only for the first time but of giving a special and private performance for each sensitive soul in the audience. It is possible to sit in the middle of a large and tumultuous crowd and still feel that Charlie is doing special little things for your own benefit which nobody else in the house can understand or enjoy.

Personally we never see him in a new picture without suddenly being struck with the thought, "How long has this been going on?" Each time we leave the theatre we expect to see people dancing in the streets because of Chaplin and to meet delegations with olive wreaths hurrying toward Los Angeles. We don't. Unfortunately Americans have a perfect passion for flying into a great state of calm about things and, for all the organized cheering from the top of the peak in Darien, we take Chaplin much too calmly at all moments except when we are watching him. Phrases which are his by every right have been wasted on lesser people. Walter Pater, for instance, lived before his time and was obliged to spend that fine observation, "Here is the head upon which all the ends of the earth have come and the eyelids are a little weary" upon the Mona Lisa.

The same ends of the same earth have come upon the head of Charlie Chaplin. Still Mr. Pater, if he had lived, would have been obliged to amend his observation a little. The eyelids are not weary. Unlike the Mona Lisa, Chaplin is able to shake his head every now and then and break free from his burden. In these great moments he seems to stand clear of all things and to be alone in space with nothing but sky about him. To be sure the earth crashes down on him again, but he bears it without blinking. It is only his shoulders which sag a little.

Charlie Chaplin as Man

CHARLIE seems to us to fulfill the demand made of the creative artist that he shall be both an individual and a symbol at the same time. He presents a definite personality and yet he is also Man who grins and whistles as he clings to his spinning earth because he is afraid to go home in the dark. To be much more explicit, there is one particular scene in The Kid in which Chaplin having recently picked up a stray baby finds the greatest difficulty in getting rid of it. Balked at every turn, he sits down wearily upon a curbstone and suddenly notices that just in front of him there is an open manhole. First he peers down; then he looks at the child. He hesitates and turns a project over in his mind and reluctantly decides that it won't do. Every father in the world has sat at some time or other by that manhole. Moreover, in the half suggested shake of his head Chaplin touches the paternal feeling more closely than any play ever written around a third act in a nursery on Christmas Eve. We can all watch him and choke down half a sob at the thought that after all the Life Force is supreme and you can't throw 'em down the manholes.

Many a good performance on the stage is purely accidental. Actors are praised for some trick of gesture or a particular note in the voice of which they are quite unconscious. We raved once over the remarkable fidelity of accent in an actress cast to play the role of a shop girl in a certain melodrama and it was not until we saw her the next season, when she was cast as a duchess, that we realized that there was no art about it. Chaplin does not play by ear. His method is definite, and it could not seem so easy if it were not carefully calculated. He does more with a gesture than almost anybody else can do by falling downstairs. ' He can turn from one mood to another with all the agility of a polo pony. And in addition to being one of the greatest artists of our day he is more fun than all the rest put together.

There must be a specially warm corner in Hell reserved for those parents who won't let their children see Charlie Chaplin on the ground that he is too vulgar. Of course, he is vulgar. Everybody who amounts to anything has to touch earth now and again to be revitalized. Chaplin has the right attitude toward vulgarity. He can take it or let it alone. Children who don't see Charlie Chaplin have, of course, been robbed of much of their childhood. However, they can make it up in later years when the old Chaplin films will be on view in the museums and carefully studied under the direction of learned professors in university extension courses.

"Mr. Pim Passes By"

NOTHING in the theatre last month has been quite so interesting as The Kid, but naturally this does not brand it as a dull period. The Theatre Guild has substituted A. A. Milne's Mr. Pim Passes By for Heartbreak House and the comedy by Punch's young man is exceedingly amusing. Nor is it mere foolery in spite of the fact that it is generally cast in light mood. Under somewhat fantastic and sparkling dialogue runs the thread of a perfectly sane and serious study of marriage.

As a matter of fact, Milne comes close to rather bitter ironic comedy on several occasions and then sheers off. He feels his responsibility as a funny man just a shade too much. Perhaps, he fears that if he attempted to do his theme in deadly earnest nobody would take him seriously. Accordingly, he does not quite take himself seriously and the final act of his play is made comic rather by resolution than by logic.

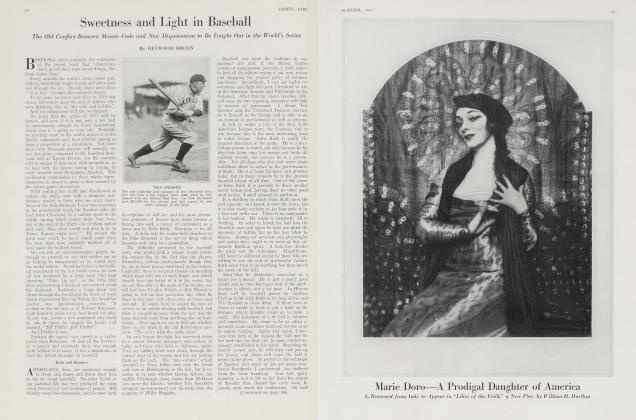

The Guild has been fortunate enough to hit upon the happy thought of casting Laura Hope Crewes as the heroine and the spark which rises when this fine light comedienne comes in contact with a brilliant play is dazzling. Miss Crewes is never too light. She inspires just a shade of reserve in all your laughter. There is body as well as flash to her performance and when the need arises she has not the slightest trouble in swinging into a serious scene and making you believe it. In nothing which she does is there the least waste effort. She says a good deal with silences and in one particular scene in which she is equipped with needle and thread she proves positively eloquent in her sewing. Dudley Digges, a fine actor, suffers from the misfortune of being miscast. The play concerns a bluff English country gentleman who discovers, or believes he has discovered, that he and his wife through an unfortunate accident have committed bigamy. Miss Crewes as the wife is not vitally concerned by it all. Happiness is her one interest in the matter, but the husband is unable to see beyond morality, tradition and good form. At the end of the play all misunderstandings must be cleared away so that this couple of divergent views can settle down once more and live happily ever afterwards.

Granting that Milne has attempted to make comic complications out of a situation which honestly implies the tragedy of incompatible points of view, it is only fair to say that Digges makes the reconciliation seem a little less plausible than it might in other hands. The saving virtue of the husband, who proves small comfort to his wife in time of difficulty, is that all his errors are of muddle-head and not of muddle-heart. Digges simply can't achieve the stupid geniality which should make the man acceptable. For many seasons now he has been playing parts touched by the East Wind and he is unable to escape a touch of sharpness in his performance. So strong a trace of whining remains that it gives false colour to what should be mere bewilderment.

(Continued on page 102)

(Continued from page 29)

Collaboration with Shakespeare

ANOTHER play imported from England has fared less happily than Mr. Pim Passes By. Macbeth was of course brought over some years ago, but Mr. Hopkins supplied new scenery and costumes for the revival. The scenery at any rate was just a little too new. Of its value as decorative art there ought not to be much question. Robert Edmond Jones is one of the great artists and architects of the stage, but his fine and potent imagination carried him farther than Shakespeare had intended to go. This, of course, is surmise, but with much more certainty it can be said that Jones set a mark to which the actors were unable to follow him. There was no proper co-operation between playwright, artist and actors. Collaboration with Shakespeare becomes increasingly difficult and he seems hardly the person to be brought into association with the newer art forms.

Within the intention of Jones was the notion of taking Macbeth out of time and place and making it an abstract play of the clash of man and the evil forces outside him. The witches were symbols and not persons and the artist put them into masks. The castle, too, was touched with symbolism. Never a liveable habitation, it leaned farther and farther from the perpendicular as the play went on, and Macbeth's downfall approached. All this we feel was not within the intention of Shakespeare, and it seemed to us hardly more suitable than if Jones had undertaken to do Crooked Gamblers and had indicated the coming decline in the rubber stock, around which the play was written, by painting the Woolworth Tower on the backdrop leaning hell-bent for Pisa.

Whatever Shakespeare thought about it, the actors were puzzled. It may not have been the scenery of Mr. Jones. Perhaps, as somebody has suggested, the audiences were unduly conscious of the scenery only because there was practically no acting to distract their attention. Julia Arthur was a likeable Lady Macbeth, which is not quite right, but Lionel Barrymore was a most dreary and tiresome Macbeth, and that's not right either. Whose the fault we don't know. We are not disposed to deny that the blame may even belong to Shakespeare; but the fact remains that Macbeth in the Hopkins production was deadly dull. In other respects the wicked Scot may have been guilty, but a large number of persons in the audience upon hearing the charge "Macbeth hath murdered sleep" would have been obliged by every dictate of justice to open their eyes and shout "Not guilty".

Of the newer plays one of the most promising is The Hero, by Gilbert Emery, who was once known as Emery Pottle. Mr. Pottle is still feeling his way about in play construction and every now and again he would trip over the plot, but he was deftness itself in the manipulation of dialogue. Character, too, he generally saw clearly. The play is an unusually uncompromising study of the glamorous virtue which we call courage. Mr. Pottle is not disposed to be blinded by it and he points out that a man may dare and dare and yet be a villain. He contrasts a steady stay-at-home brother and a young rascal who gathers glory as he rolls into war and then comes home to live on his bravery and nothing else. Probably Mr. Pottle intends to make us see that there is more persuasive appeal in the courage which faces the hard, daily unromantic tasks than the more special sort for which medals are awarded. In this the author does not quite succeed. He slashes most of the gloss off the war hero through three acts, then he lets him die a hero and, though it is illogical, the last fine gesture of the man blots out almost everything else.

Perhaps this very effect is within the intent of Pottle, who may choose to press home the irony of his comedy of the stay-at-home to the point of tragedy. Mr. Pottle still does men a great deal better than women. The wife of the humdrum brother does not seem very clearly drawn and the Belgian refugee who falls into the path of the hero is no more than another doll in the great sawdust army of the seduced. But both the brothers are drawn with rare understanding and enormously well played by Robert Ames and Grant Mitchell. If he has so,me luck and enough application Mr. Emery ought to go on to be one of the native dramatists entered in the contest for the making of the great American drama.

"Nice People"

RACHEL CROTHERS is not so keenly in the competition as she seemed to be when she wrote Old Lady 31. Her Nice People is moderately amusing but it follows the convention of every little old last year's Sunday magazine story in becoming much exercised over the morals of the young today. We doubt the accuracy of the observation of the pessimists and we are still more certain that whichever way the facts point nothing very important is at stake. We are rather inclined to think that the somewhat important matter of morals has been confused with the lesser question of manners. However, in justice to Miss Crothers it is only fair to add that she has written a good part for Francine Larrimore and that Miss Larrimore plays it as if it were a great one.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now