Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Well-Made Revue

A Little Less Finish and a Little More Fine Careless Rapture Wouldn't Hurt the Revues

HEYWOOD BROUN

ONE of the simplest ways in which a critic can put a play in its place is to refer to it as "well made". The phrase has come to be a reproach. It suggests a third act in which the friend of the family tells the husband, "Take her out and buy her a good dinner", and the lover decides that he will go back to Mesopotamia—"Alone!"

George Bernard Shaw changed the style, and taught playgoers to refuse to accept technique as something just as good as spiritual significance. We now await the revolt against the well-made revue. Each of the Ziegfeld Follies is perfect of its kind, but just as in the plays of Pinero, form has triumphed over substance. The name Ziegfeld on the label means a magnificent product perfect in every detail with complete satisfaction guaranteed, but it is a standardized product. You know just what you are going to get. Ziegfeld scenery, Ziegfeld costumes mean something definite. Even "a Ziegfeld chorus girl" suggests an unvarying type. The hood is as unmistakable as that of a Ford automobile.

At times one is struck with a longing to find a single homely girl among all the merry marchers. And there is at least a shadow of a wish to encounter, likewise, something in a song or a set or a costume rough, unfinished and ungainly. Alexander sighed and so might Ziegfeld. His supremacy in the field of musical revue is unquestioned. Even the shows with which he has no connection follow his modes as best they can, though sometimes at a great distance. He really owes it to himself and to his public to put on, in the near future, a very bad revue so that in the ensuing year that most precious element in entertainment— surprise—may again come to the theatre through him. The first of all the Ziegfeld Follies must have furnished its audience with a night of startled rapture. The rest have produced a pleasant evening.

The Irresponsible Revue

BURDENED by years of success, Mr. Ziegfeld must be hampered by innumerable rules about revue making. He has created tradition and probably it rises up in front of him now and again to bark his shins. The Follies is still an entertainment, but now it is also an institution. Plan, premeditation and the note of service must all have won their places in the making of each new show in the succession. The critic will not depart in peace until he has seen somehow, somewhere an altogether irresponsible revue. It will be produced not by Edward Royce but by spontaneous combustion. Some of it will be terrible. Few of the costumes will fit and many of them will be in bad taste. None of the tunes will be hummed by the audience as it leaves the theatre. But, nevertheless and notwithstanding, this irresponsible revue of which I speak is going to contain two good jokes.

I had at least a glimmer of hope that Shuffle Along might be the first blow of the revolution against the well-made revue. Early explorers in the Sixty-Second Street Music Hall came back glowing with discover)'. And yet after seeing the negro revue it seems to me that stout Cortes and all his men were duped. In book and music and dancing Shuffle Along follows Broadway tradition just as closely as it can. It is rough with old things which have crumbled and not with new things which are unfinished. And yet it is easy to understand the thrill which swept through some of the pioneers who were the first to see Shuffle Along. In it there is one quality possessed by no other show which has been seen in New York this year. Most musical comedy performers seem to be altruists who are putting themselves out to a great extent in order to please you and the other paying customers. Shuffle Along is entirely selfish. No matter how enthusiastic the audience, it cannot possibly get as much fun out of the show as the performers. Not since the last trip to New York of the Triangle Club have I seen the amateur spirit more fully realized in the theatre. Perhaps the performers get paid, but it does not seem fitting. The more engaging theory is that each member of the chorus of Shuffle Along who keeps his work up at top pitch until the end of the season receives a large blue sweater with a white "S. A." on the front and is then allowed to break training. The ten best performers, in addition, are tapped on the shoulder. There is a rumour that social distinction as well as merit enters into this selection, but it has never, to my knowledge, been confirmed.

Of course, nothing in the remarks above is to be construed as implying that people in the Ziegfeld choruses do not have a good time. Such a statement would certainly be far from the facts. As somebody or other has so aptly said, "It's great to be young and a Ziegfeld chorus girl". The difference is that no Caucasian chorister, including the Scandinavian, has the faculty of enjoying herself with the same frankness and abandon as the African. Centuries of civilization and weeks of training make it impossible. The Follies girl knows what she likes, but she has been taught not to point. A certain reserve and reticence is part of the Ziegfeld tradition. Even the most daring of Mr. Ziegfeld's experiments in summer costuming are more aesthetic than erotic. Though the legs of the longest showgirl may be bare, one feels that she is clothed in reverence. When the lights begin to dim, and the soft music sounds to indicate that the current Ben Ali Haggin tableaux is about to be disclosed, I am always a little nervous. So solemn and dignified is the entire atmosphere of the affair that I feel a little like a Peeping Tom in the presence of Godiva and generally I cover my eyes in order that they may be preserved for the final processional in which one girl will be Coal, another Aviation and a third the Monroe Doctrine.

The parade is one of the traditions of the Follies. "When in doubt make them march", is the way the rule reads in Mr. Ziegfeld's notebook. All of which opens the way to the suggestion that Mr. Ziegfeld should try the experiment some year of cutting about $100,000 out of his bill for costumes and using the money to buy a joke. In that case the marching chorus girls could pass a given point.

The Achievements of Mr. Ziegfeld

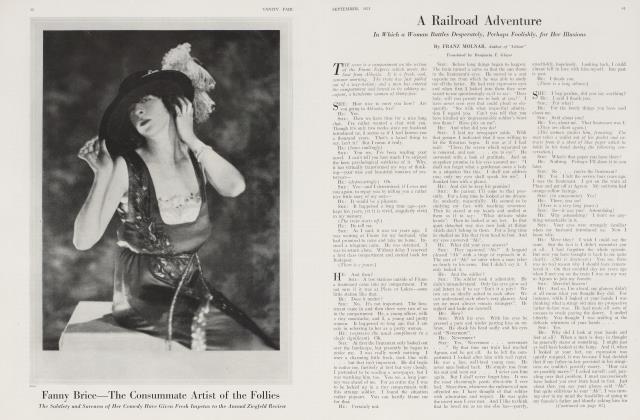

IT would be unfair not to admit that the technical plan upon which each of the Follies is built is still flexible enough to include a great variety of performers. Moreover, Ziegfeld is still an experimenter with new styles of design in the theatre. He has done more to bring scenic beauty to the stage than any other producer in America with the possible exception of Arthur Hopkins, who had the wisdom to make an alliance with Jones. If the Theatre Guild can consistently maintain.the standard it set in Liliom and a season or so ago in The Faithful through the brush of Lee Simonson, Ziegfeld may have to look to his laurels. We rather think he does, but his interests are limited to things of visual appeal. There is not much evidence that he cares particularly about verbal humour. Indeed Broadway gossip has it that Channing Pollock was repulsed again and again with heavy losses when he attempted to introduce satirical interludes into the Follies. Still, Mr. Ziegfeld has been chiefly responsible for a few notable comic performers. No one has "been able to take the place of Will Rogers, but the present Follies contains another artist of the first rank. Fannie Brice is at her best in singing Second Hand Rose. She is a great clown and possesses, as' is almost always the case, the lining of pathos which takes the sharp edge from comedy. Only a Fannie Brice could make the sentiment of My Man anything but slushy. It would be interesting to see her in a legitimate part, in something by Fannie Hurst for instance. The experiment was tried once in a play by Montagu Glass, but it was not in his best vein. Though I am loyal in my allegiance to the irresponsible revue which is to be written some day and which will touch life more closely than anything which Mr. Ziegfeld has produced, I can imagine few places more pleasant in which to spend the waiting years than at The Follies of 1921.

(Continued on page 92)

Continued from page 33

The Winter Garden

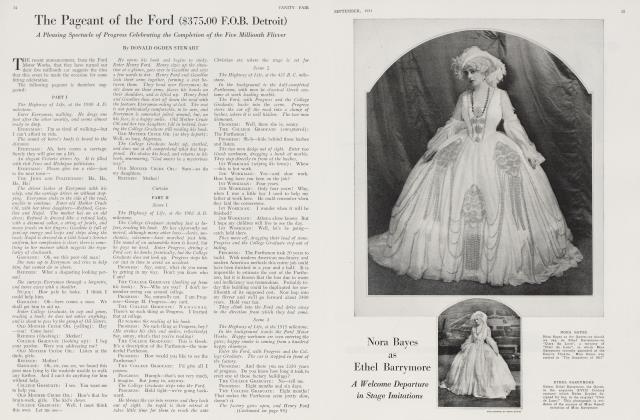

TO appreciate Ziegfeld one ought to see a Winter Garden show every now and again. The present vehicle The Whirl of New York ought to do as an example, because it is better than most of the Winter Garden shows except those which have A1 Jolson. It is indeed pretty good entertainment in a clumsy sort of way. This clumsiness might be a positive virtue if it were not for the fact that The Whirl of New York is designed to be a well-made revue and never quite gets there. There is too much of everything, too much colour and far too many chorus girls. The Winter Garden still clings to the heresy that if a certain effect-can be obtained by using twenty chorus girls, it must necessarily be just five times as captivating with a hundred people upon the stage. However, the show serves to prove that Dorothy Ward is a much more effective performer than anybody could have imagined after seeing her in Phoebe of Quality Street. The young woman does not belong in a china shop. Once she was freed from the necessity of behaving like a Barrie heroine she kicked up her heels and proceeded to be a jolly sort of a person in a loud, boisterous, good humoured sort of way. She needs at least a Winter Garden in which to turn a piece of acting, but she has splendid vitality and a fetching sense of pace.

The only other performer in the show who made any lasting impression on this first nighter was Kyra, a remarkable dancer who did The Spirit of the Vase and all that. It is not exactly a novelty, for instance, to try to create the illusion of writhing cobras with two thin arms and a pair of imitation emerald rings, but it must be said for Kyra that this time full and complete justice was done to the snakes.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now