Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowAnd the Moral of That

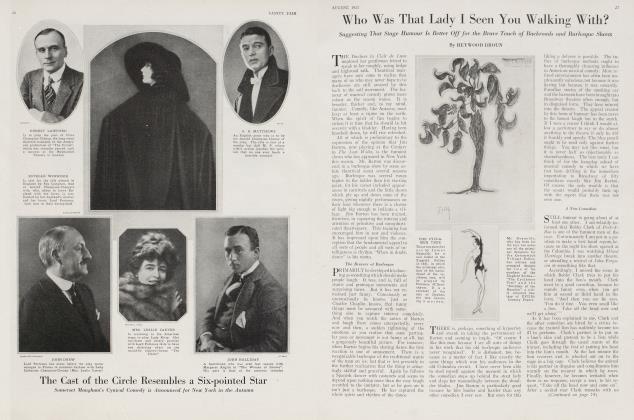

Playwrights of the Month Set Themselves to the Task of Making Mankind and This World a Little Better Than They Found It

HEYWOOD BROUN

IT is always flattering to discover that the playwright is trying to reform you. The transgressor is puffed up by the thought that his vices must be interesting and important. Unfortunately, the trend of the dramas of the month has been of a character to make us conscious and regretful of a blameless past. Wine, women and wiggily dances are the objects of attack and though we find these themes interesting and academically instructive we are never able to achieve the proper mood of rampant remorse which ought to mark the climax of a soul's adventure with each of the reform masterpieces.

Possibly this admission of aloofness from the matters under discussion should disqualify us from an expression of opinion. Still, we did venture to review Liliom even though it dealt with both hell and heaven. Granting then, that we speak from no expert's standpoint it seems to us that Hartley Manners has overemphasized the importance of jazz in The National Anthem. He has armed himself to slay a dragon although his prey is actually a hoptoad. If the spectator is willing to grant the original premise of Mr. Manners that jazz is a factor threatening national safety it must be admitted that the playwright has done a workmanlike job in his effort to abate the evil. There is not much merriment in The National Anthem but if things are actually as bad as the playwright believes he may be pardoned for a consistent severity of treatment. Some monsters are not to be destroyed by tickling them in the ribs.

Technically there is much adroit manipulation in the play. The manner in which the jazz orchestra has been synchronized into the action of the piece is ingenious. To us it seems a little over ingenious. Our almost constant feeling at the first night was "Isn't this clever and difficult." We were always afraid that some time or other when a door was opened or a window raised the music would not swell up in full volume at just the proper moment. After all, the cues for the jazz players were so many that it would have been easy for them to slip up. We have somewhat the same feeling about trained animals in plays. However, there were no mistakes. Mr. Manners was unimpeded in his hard persistent drive against jazz.

Most of it is infighting. The dramatist gets close to his theme and stays there pumping away with both hands. And the struggle did not hold our interest at the highest tension throughout. Jazz is not really important enough to take quite so much of an excellent playwright's attention, role has been crer Laurette Taylor but it is not one which calls into play all her talents. Comedy has been pretty rigorously excluded. Miss Taylor has some exceedingly eloquent moments but the lack of variation in the key is sometimes a handicap which she cannot overcome. For instance, the requirements of the plot make it necessary for her to be drunk during an entire act. Ralph Morgan as the hero has to be drunk for two acts. Anybody who happens to have erring friends knows that there comes a point in any given period of time when an intoxicated person is neither comic nor tragic but just a nuisance.

The theatrical presentation of the state is of course milder than this, but even so a diminution of interest is inevitable. Ralph Morgan, for example, has thrust into his hands in the first act a scene in which he is called upon to fly into an alcoholic and hysterical rage. He accomplishes this magnificently and thereafter there is nothing which he can do to grip the attention so closely.

Mr. Manners has been quite frank to admit the propaganda nature of his play. It has been written with an extended forefinger. Many other dramatists of the month have been equally intent on shaping the world a little closer to the heart's desire but most of them have sought to conceal the fact that their plays were also sermons. Marc Connelly and George Kaufman, the authors of To The Ladies, are not likely to be discovered in their campaign against the buncombe of business because they approach their theme with open and smiling countenances. Still, it seems to us that no after dinner speaker who has seen To 'The Ladies will ever be quite the same man again. This time the exposure of a sin touched us closely. The banquet scene stepped on our toes and wrung our heart. We left the theatre intent upon reform. The play also made us regretful for all the effort we have put into the development of efficiency. We decided to scrap that quality out of our life.

Progressing Playwrights

TV THE. LADIES seems to us an advance over Dulcy. The satire is much more abundant and just as keen. It may well be that the scene in which the audience faces the speakers' table at a public dinner is the best piece of native satire which the theatre has seen since George Ade wrote The College Widow. There is not quite enough satire to round out the evening and the authors have pieced out their pattern with heart interest. Some of it seems authentic to us. There is the suggestion of real feeling in To The Ladies, but this quality is not sustained. The play slips off toward the end into familiar stratagems. The story itself is not notable although it has afforded one conspiciously good situation during the dinner act, but the playwrights have had the excellent judgment and presence of mind not to become in the least disconcerted even when out of touch with the plot. Cut off from their base they proceed merrily upon their way. Some of the funniest things in the evening's entertainment are only remotely connected with the story.

As a matter of fact, humorous and accurate observation is always welcome in the theatre whether it figures as main theme or interlude. There are times when To The Ladies seems almost up to the level of The First Year but it has not the same sustained truthfulness and it does not cut so deeply. The first night performance, although a rousing show, was not quite fair to the potentialities of the manuscript. Satire is so rare in the theatre that actors do not recognize it easily. Otto Kruger insisted often in transforming it into burlesque. This may well be a failing which the play will outgrow in the course of time.

Continued on page 108

Continued from page 39

Madame Pierre, the new adaptation of Brieux's Les Hannetons, is also distinctly propaganda. The method is ingenious. Brieux is intensely serious. There are many things in the play at which audiences may laugh and do, but if they will stop to reflect for a moment they will find that it is very bitter merriment. But Brieux steadfastly avoids didacticism. His moral is never mentioned but must be picked up from the context of the play. To be sure there is no difficulty in doing that. The thing which bothers him is that men delude themselves by thinking that the obligations of marriage may be avoided simply by omitting the ceremony. Pierre's apartment is completely furnished in every respect except for the embossed paper. He finds that his freedom is wholly an illusion. Not even the remedy of divorce is open to him. The young person in the social partnership absolutely refuses to be dismissed and in the end we find her settling down for good despite the reluctance of Pierre. The comedy is beautifully played particularly by Roland Young who manages to keep the comedy light and yet never fails to lift a scene to an emotional quality when there comes a turn in the mood. Estelle Winwood is also excellent.

An even better play from the French is The Nest of Paul Geraldy in a translation by Grace George which seems admirable. This comedy is the inevitable answer to the variations which motion picture producers and playwrights have devised upon the theme of home. Geraldy says in effect that it is inevitable that the family should disintegrate when the children grow up. He says this without either cynicism or sentimentality, although he recognizes the tragedy of the deserted mother.

If the play must be classified under a label hardly anything will quite do but tragi-comedy. It is clearly a story of the frustration of a human will by the impregnable attack of inevitable circumstances. Its fineness seems to us to be vastly emphasized by the simplicity of the materials employed. Nobody goes mad or dies in the centre of the stage, or anything of the sort, to point the tragedy. No, the tragedy lies in the fact that a woman who expected to be urged to stay to dinner is merely invited. Lucille Watson does well with the rôle of the mother, but the performance which impressed us most was that of Christine Norman. This seems to us as eloquent a piece of playing as we have seen all season. There is an extraordinary sturdiness and drive to the method of Miss Norman. Once she has started to conquer a scene there is no stopping her. She has a force and momentum which is irresistible. Her work in The Nest is brilliant in the extreme.

Doris Keane contributes a gay and happy performance to animate The Czarina. This is an Hungarian version, by Edward Sheldon, of the loves of Catharine of Russia, Catharine receives somewhat less respectful treatment than that accorded to her by Bernard Shaw. Mr. Shaw satirized the amorousness of the queen but he was entirely serious whenever he touched upon the ecstasies of her mind. For all the broad farce of his Great Catherine she came out of the ordeal a magnificent person. Neither the playwrights nor Miss Keane have made Catharine quite that. Miss Keane is seductive, continuously amusing and in one flash eloquent but the queen remains a picturesque personality rather than an impressive one.

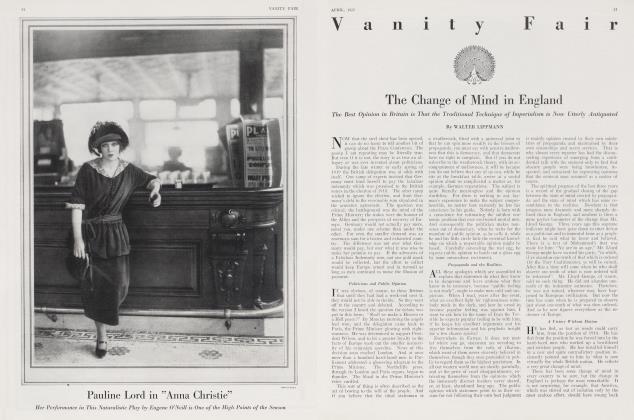

The revival of The Pigeon serves to allow Whitford Kane to give a really startling performance in the role of Galsworthy's illogical philanthropist. The Deluge on the other hand is chiefly notable in revival for the absence of Pauline Lord. Second sight of this piece makes it seem far more tricky than it did before. There is an excellent idea to build upon but it has been followed somewhat too slavishly.

In the field of musical entertainments there is of course nothing comparable to the Chauve-Souris which is vaudeville gone to heaven. On a plane far lower but still agreeable lives Marjolaitie. This is just a trifle too sweet to be admitted into the realm of the blessed, but we have no doubt that they lean now and again over the gold bar to listen to the singing of Miss Peggy' Wood and to watch the antics of Miss Mary Hay.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now