Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowSocratic Dialogues of the Moment

Discussing What it is That Makes Literary Men Go On Writing After They Realize They Have Nothing to Say, and Proposing a New Scheme for the Relief of Aesthetic Lions

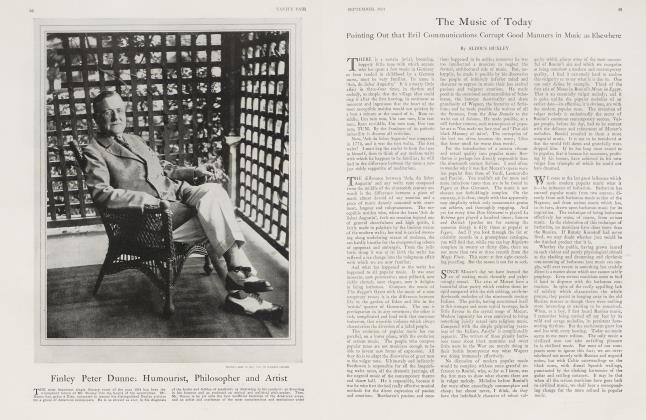

ALDOUS HUXLEY

THERSITES: A distinguished man of letters. TYRO: A beginner.

TYRO: Tell me Thersites—for I am collecting this information along with specimen autographs from all living writers—what was it that first decided icided you to become an author?

THERSITES: I will tell you, my dear Tyro. I embarked upon the career of letters because I was naturally endowed with a gift of expression and because I thought, when I was young, that I had something to express that would be of importance to the world at large. I still retain my gift of expression: indeed, I can write better and more fluently today than I did twenty years ago. But as for having anything important to sav—alas, I have quite got rid of that illusion now.

TYRO: YOU astonish me, Thersites. To me you seem to say things as extraordinary and illuminating as ever you did.

THERSITES: I go on quietly repeating myself with variations. That is all.

TYRO: But if that is really so, Thersites, why do you go on writing at all ?

THERSITES: For several very good reasons, my young friend. To begin with I am committed by my own previous achievement to follow this odd career to its obscure end. The public listens to me, even believes in me long after I have ceased to believe in myself, I appear to exercise something like an influence upon my contemporaries. Nobody likes to abandon power once obtained, in this respect we are all Lloyd Georges. That is one reason why I go on writing. In the next place I have to consider the fact that, if I stopped turning out my ten thousand words a week, I should starve. For by this time, my dear Tyro I am quite incapable of earning an honest living or of doing anything in the nature of real hard work. Given the necessary talent—and one needs very little, you know, very little— one can make one's living more easily and agreeably by writing than in any other way. There are no regular hours in the literature business, there is no office, no commercial interest to chain you to one particular spot on the earth's surface. You may write where, when and how you like. And the process is really not at all unpleasant. . . . Writing is very little more trouble than talking, and to write well you need very little more talent than is required to make a good talker. How many other professions are there in which one can earn enough money to enjoy oneself by making no more effort than is required to talk intelligently and entertainingly at an. evening party? I can think of none more agreeable and less strenuous, except perhaps those of the tramp and the souteneur.

TYRO: That is a reason for embracing the career of letters, of which, I must confess, I had never thought.

THERSITES: It is true that many practitioners of literature assign as their motives for exercising the trade much higher, nobler, and weightier reasons. They pretend that it is of immense and somehow cosmic importance that they should write their yearly novels and their four column articles on Shakespeare and Marcel Proust in the weekly journals of opinion. They cannot admit that they are merely frogs; they have to blow themselves up into the semblance of.cosmic oxen. The spectacle is a little pathetic.

TYRO: But what about art, Thersites, what about philosophy, what about the basic, the fundamental mysteries of existence? And what about fame and immortality?

THERSITES: Yes, what about them, my young friend, what about them?

The Hunted Lions

MAEONIDES: A Poet.

ZEUXIS: A Painter.

MAEONIDES: I hear I'm to have the honour of meeting you at the energetic Mrs. Charybdis's tomorrow night at dinner. (He takes an invitation card out of his pocket and reads) "To meet Mr. Zeuxis." It will be charming to make your acquaintance officially, so to speak, after so many years of mere vulgar friendship.

ZEUXIS: Yes, it seems to set a seal on our relations, doesn't it.

MAEONIDES: And it guarantees us both to be genuine celebrities. We have Mrs. Charybdis's hall mark stamped all over us.

ZEUXIS: Warranted eighteen-carat solid talent. It's a pleasing thought.

MAEONIDES: It's magnificent. But seriously, Zeuxis, isn't it time we did something about Mrs. Charybdis and her companions in the lion hunting business?

ZEUXIS: DO what, Maeonides? You might as well try to do something about an earthquake or a tidal wave. Mrs. Charybdis is a force of nature.

MAEONIDES: Wild birds, walruses, whales and hippopotami are protected from the destructive activities of the hunter. And why not we? Are we poor scribblers and daubers to be the only creatures that may be hunted without mercy or respite all the year round ? We are not even allowed a closed season. The very oysters get that.

ZEUXIS: True, Maeonides. But, after all, it is partly our own fault for permitting ourselves to be hunted. If we dug deep into our burrows and remained there, the hunters would never be able to get at us at all.

MAEONIDES: YOU are right there, Zeuxis. It is a weakness in us; a weakness due in part, no doubt, to common snobbery, but more, I like to think, to the pathetic hope and belief that we shall some day be lured into a real salon where, under the auspices of some charming and intelligent hostess, we shall be able to meet our fellows and indulge in reasonable conversation on subjects in which it is possible to take some interest. But how vain that hope is! The woman who combines distinction, wealth, charm, tact, and intelligence must always have been rare. But, at the pres • ent moment the species seems to be as wholly extinct as the dodo.

ZEUXIS: Only the Mrs. Charybdises survive.

MAEONIDES: Only the Mrs. Charybdises. . .

ZEUXIS: The most intolerable thing about these women is that they think they are patronising art and letters whenever they ask you out to a meal. As a matter of fact, all that they are doing is simply to interrupt you in the middle of your day's work. I do not benefit in any way by accepting a meal at Mrs. Charybdis's. Both spiritually and financially I am a loser by it. The hours I spend there distract my mind and prevent my doing what might be a piece of lucrative work. If she'd buy one of my pictures every six months, instead of asking me to luncheon or dinner every fortnight, I should be extremely grateful to her. As it is she prefers to patronize art by making me waste my time.at her house—and never, never, by any conceivable chance does she buy one of my pictures.

MAEONIDES: She doesn't even buy my books. If she wants to read them, she borrows them from the circulating library.

ZEUXIS: All this has got to be altered, Maeonides. We must begin by making it quite clear to the Charybdis and her fellow hunters that it is we who are conferring the favour in coming to their houses, not they in asking us to eat there.

MAEONIDES: That will have to be regarded as fundamental, axiomatic.

ZEUXIS: After that we shall have to put the whole thing on a sound commercial basis. A scale of charges must be agreed upon. Thus, for every three luncheons or dinners that I eat at Mrs. Charybdis's, she must buy a picture of so many square feet surface area at so much per square foot. You see the idea. Both of us would be gainers. I should have a regular market for my work and Mrs. Charybdis an excellent collection of modern pictures. The arrangement seems to me perfect.

MAEONIDES: For you painters, perhaps.

But what about us who write? We can't make the Charybdis buy our books by the dozen and the gross. That would be unreasonable—and besides, it would only benefit the publishers— and that is a form of philanthropy to which I for one, would conscientiously object.

ZEUXIS: Well then, she'll have to buy your manuscript; so many lines every time you set foot in her house at so much the line.

MAEONIDES: Excellent. All that now remains to be done is to form a trade union of all the lions and potential lions, so that the new rules can be universally enforced. All scabs and blacklegs will be ruthlessly dealt with.

ZEUXIS: I'll beat up the painters.

MAEONIDES: And I'll collect the literary men.

ZEUXIS: Good-bye then. Let us wish one another luck in this great and noble enterprise.

MAEONIDES: With all my heart. (They shake hands, then exeunt severally.)

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now