Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowAmerica and Caricature

Suggesting that in Our Haste to Honor European Artists We Have Unduly Neglected Our Native Caricaturists

WILLARD HUNTINGTON WRIGHT

CARICATURE—that spirituel and sophisticated offspring of the graphic art— does not thrive in America as profusely or proficiently as it does in the older countries of Europe. Caricature is a highly cultivated form of expression which, for its development, requires an atmosphere of philosophic dalliance. As an art, it is but partially pictorial: its chief ingredient is intellectual observation. Indeed, technique is secondary. Though an aspirant may have the facilite de main of a Picasso, he is not eligible for the select and ancient order of caricaturists, unless he possesses a broad intellectual culture with highly developed analytic and critical faculties. His means of expression are relatively unimportant.

Max Beerbohm is an excellent case in point. Here is a famous modern caricaturist whose reputation rests almost entirely upon his intellectual and temperamental capacities. His most ardent defenders have never held a brief for his craftsmanship. His drawing, in fact, is at times amateurish; and not even in his most finished productions is there to be found the adroitness and inevitability of line which mark the work of the Simplicissimus group of caricaturists — Thony, von Blix, Heine, Arnold, Gulbransson, et al.

The Literary Max

THE cultural and intellectual gifts which alone have given "Max" a conspicuous niche in the history of his craft, are the very qualities in which American caricaturists, as a whole, are most deficient. This fact, however, is, by no means, a reflection on the men themselves. A congenial and sympathetic atmosphere of intelligent interest and critical appreciation is a highly important factor in the development of the art of caricature. Moreover, caricature is essentially a manifestation of a nation's maturity. A young nation, still in its incunabula, can no more produce finished caricaturists than an adolescent youth can raise a beard.

Also, the technical medium, by which a caricaturist bodies forth his ideas and observations, is a matter of long, slow growth. There have been no youthful prodigies in this art, as in nearly all the other forms of aesthetic creation. We have infant pianists and composers,—there is the famous picture showing the lost four-year-old Schubert, being found in the attic playing one of his own compositions. And almost every season produces one or two juvenile genii in painting. Then, there are the various infantile novelists. Indeed, we have been overburdened of late by the masterpieces of the Daisy Ashford type.

But the caricaturist in arms is unknown; and will continue to be. In fact, nearly all workers in this field, who have achieved renown, are well past even the "bright young man" stage.

America, despite her youth and the lack of thoughtful leisure which makes possible the growth of the greatest caricaturists, has developed several artisans of a high and promising order in this restricted field.But, as a nation, we fortunately have always been somewhat prone to underestimate the achieve-

ments of our own men. The imprint of Europe—the magic "imported" label—has, because of a too prevalent intellectual snobbery, resulted in a grave injustice being done the creative workers in America; and time and again we have placed the bay leaves upon the heads of European artists (to say nothing of the dollars we have put in their pockets) when fully as competent and deserving native men have gone unnoticed and unrewarded. This is as true of caricature as in the other arts.

Of late years, and especially since the war, America has shown a tremendous increase of interest in the art of caricature. There is no gainsaying the fact that the war tended to mature us. It forced us into closer contact with the grim realities of life. It taught us new values—both naturalistic and philosophic. It gave us a deeper insight into the mainsprings of human motive and emotion. And, above all, it brought us in more intimate touch with the various phases of European culture.

It was inevitable, therefore, that our interest in caricature should be aroused more fully; for, of all the arts, this is the one which, in popular fashion, reflects most clearly the realism and humanism of mere visual existence.

The evidence of this interest may be remarked on every hand. There has been an activity, amounting almost to a fad, centering about the works of Max Beerbohm; and the widespread demand for his caricatures has raised the price of some of his older collections to three and four times their original value. Even Simpson's series of modern English celebrities sold with astonishing rapidity in America, and are now at a premium. Many of the American magazines—and not alone the art journals—are devoting pages to pictorial satire. Numerous publications are running series of caricatures; and it is not uncommon for these periodicals, instead of illustrating personal articles with photographs, to make use of caricatures instead. Even our daily newspapers reflect the general interest in satirical portraiture; and when we open a paper today we are as likely as not to be confronted by a caricature of some celebrity of the moment. Furthermore, a New York theatre has recently introduced an innovation by ordering a drop curtain decorated entirely with caricatures.

American Caricaturists

THE time has come when attention should be called to the men in America who are laboring seriously and capably in this field. Although Europe possesses such men as Gulbransson, Thoney, Tirelli, Arnold, Tovar, Forain and Sem, who lead the world today in caricatural art, there are, nevertheless, in this country men who have achieved something well worth while, and who are unquestionably the superiors of many Europeans—such as Raemaekers, for example—who have gained enviable reputations in America.

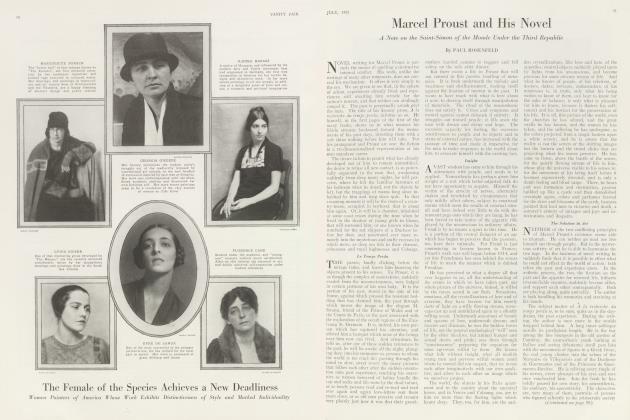

Among the men who have achieved proficiency and individuality in caricature in the United States, yet who have failed to receive their due, may be mentioned Boardman Robinson, Cesare, Art Young, George Bellows, William Gropper, T. S. Sullivant, Ralph Barton and Alfred Frueh.

Each of these artists has, in some degree, evolved an original and characteristic technique. And each of them contains something of the matured and analytical spirit which indicates the true caricaturist, and distinguishes him from the mere cartoonist or illustrator. Perhaps not one of them is a caricaturist in the highest sense—indeed, there are only a few such in the world—but each one has come a considerable distance along the road which leads to that difficult goal.

Cleverness is perhaps the most conspicuous characteristic of American assthetic endeavor; and I believe that it is one of the principal causes of the superficiality of much of our art. Not only does cleverness tend to detract the mind of both critic and public from the real emptiness and mediocrity of a piece of creative work, but it also blinds the artist himself to the profounder concerns of his art.

Cleverness as a Curse

NOWHERE does this seem to apply more truly than in the field of our caricature; and while it would be unfair and misleading to condemn the men I have mentioned for their amazing adroitness of technique, the fact remains that the chief adverse criticism which attaches to them as a whole is their surpassing cleverness. Indeed, not until they have ceased to be satisfied with the external dexterity of their work, will they complete that long tedious search for the deeper and less obvious qualities of caricature. Barton, alone among them, seems to be focusing upon the interior qualities of his metier; and in many respects he is the least clever of them all—that is, he gives one the impression of caring less for his methods than for his content, and of being willing to sacrifice the surface aspect for the idea.

Cesare, on the other hand, though likewise impressionistic as to detail, works with mass and volume rather than with line and salient. His drawings are great blocks of matter, roughly sculptural in effect, and somewhat in the Heinrich Kley tradition. But in all his faces and figures there is thought and care, despite his tendency toward illustrative representation. At times, however, the impulse of the true caricaturist can be sensed, animating his vision and execution. He depends, in fact, much more on the appeal of his intellectual interpretations—even in his more obvious cartoons—than on the more complicated literary and symbolic devices which have made of American cartooning a kind of pictorial story-telling, with labels for the guidance of the imagination.

Boardman Robinson has, to a considerable extent, used his talent for political ends, although on numerous occasions he has sought to catch and set down the characteristics of individual and group types. His technical manner is almost brutally aggressive, and he is strongly influenced by the modern ideal of impressionistic suggestion. He sketches his figures roughly, with broad bold strokes, emphasizing only the salients of his theme; and his doctrines find excellent expression in the rugged manner of their transcription. I do not mean to imply that Robinson is not proficient in his capacity for detailed articulation. His technique, in fact, is a direct development from a meticulous academism, and therefore competent, forceful and accurate.

(Continued on page 102)

(Continued from page 55)

A unique and original talent is that of William Gropper, whose instinct for caricature has in it more of the Continental spirit than that of either Robinson or Cesare. Unlike either of these two men, he depends for his effects on exaggeration carried at times to the point of burlesque. He has chosen a medium of free, rapid, insecure lines, without shading or hashures, which might be described as a kind of sophisticated amateurishness. It is a difficult medium, and requires executive mastery; but Gropper has achieved noteworthy results. Moreover, he has shown that he is not without that critical and understanding intelligence which lifts a draughtsman out of the ranks of the mere cartoonist.

George Bellows confines his work in caricature largely to the depiction of types and milieus; and in this particular field he is not surpassed by any living American illustrator. His technique— a result of the Lautrec-Forain-LegrandSteinlen inspiration—is composed of broad, simple lines, laid down with a kind of careless skill, which gives to his pictures a feeling of considerable external strength and vigour. He shows clear and, at times, fearless observation in the presentation of his types, and manages often to catch the vitality, as well as the representative qualities, of his subjects.

I have included Art Young in this list mainly because of the thought and criticism which enter so constantly into his work. Young is a pictorial doctrinaire. He rarely draws a picture which has not some definite and serious idea behind it; and so well does he manage to voice his ideas by the graphic means of expression, that he deserves to be classified as a caricaturist in the broader sense of the word. At times he sums up, by a simple picture of types, an entire environment, or viewpoint, or political doctrine. He deals in human symbols, not personalities, and thus comes much nearer to being a purely philosophic caricaturist—such as Forain was in his Doux Pays—than any other American. His technique is individual, blunt, economical and naif; and he makes use of coarse, accentuated outlines after the manner of Leech.

T. S. Sullivant is a man of entirely different impulses and objectives. He is the skillful cartoonist with the instinct of the caricaturist occasionally breaking through and lifting his pictures into the realm of higher things. He depicts animals almost exclusively, but he attains results in which the characteristic spirit of his subjects is accurately caught and divertingly set forth. He depends in large measure upon grotesqueries of exaggeration and distortion; but not even his most fantastic burlesques depart from the general truth. His animals are much more than mere comic monstrosities. Furthermore, he has evolved a technique which is in perfect accord with his vision—straightforward, vigorous, and wholly distinctive.

Barton, as I have already stated, stands somewhat outside the ranks of American caricaturists. He is not a clever technician, and as yet has not succeeded in developing a personal mode of expression. His style has changed several times during the course of the past few years, and he is now tending toward the "wood-cut" manner of Thony—the fine sensitive line which makes possible the depiction of anatomical structure. But Barton's importance does not lie in his style: he is, in fact, the only one of these several caricaturists whose subject-matter is of greater significance than his means, and lie is the one caricaturist most likely to make enemies. His cultural attitude is French rather than American, and he is more interested in the subtleties of character than in external traits.

For sheer cleverness, diversity of talent, and ability to set down an interpretative likeness of a given subject, Frueh has no equal in this country. He works with a rigid economy of means, and he can construct a vivid portrait of a person with a few telling strokes. He deals in salients almost exclusively; and so keen is his observation that he is able to sum up a personality in a single feature or lineament. Moreover, Frueh is an adept at sensing the distinctive color of personalities, and he often varies his technique accordingly. Thus he gives us at times an interpretation as well as a likeness. For instance, he will project a stolid, static person by means of rigid, architectonic lines; and he will use a fine delicate line in projecting a plastic, sensitive person. But he rarely touches upon the more philosophic and cultural side of Caricature and contents himself with the exaggerations of portraiture. His very facilite is at once his attraction and his limitation; but of the narrow field he has chosen to work in he is the undoubted master. In fact, he is the superior of such foreigners as Massaguer, Alvarez, and Sirio; and he marks a decided step in the evolution of American caricature.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now