Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowMan, Lord of Machinery

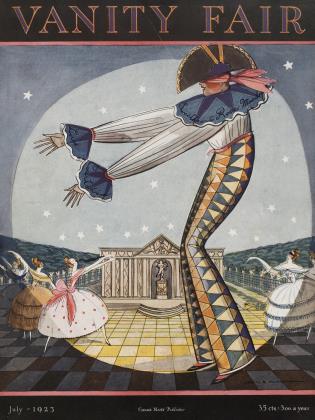

A Fantastic Cinematograph of Modern Life

ROMAIN ROLLAND Author of "Jean-Christophe

ACT I. Interior of an immense Hall of Machines. (We look down from a wide gallery, at the top of a big staircase, and survey a gigantic hall and Us crowd of machines. A moving sidewalk ascends the staircase and reaches the gallery. This sidewalk, as will be seen later, goes all around the hall, like a scenic railway, climbing to the gallery, then descending, in great loops. At the further end of the hall, it reaches a vast stage—exactly opposite the staircase. Upon this stage the ceremonies which are to follow, take place.)

It is the day of the official inauguration. The army of machines is in place, motionless.

All along both sides of the moving sidewalk, on the great staircase, around the gallery, troops in brilliant uniforms stand in a close line; the crowd presses in behind them, trying to get a glimpse of the expected procession.

Music (bands and choruses). The soldiers present arms. The procession appears and is enthusiastically acclaimed. It is carried, slowly, with a slightly grotesque majesty, upon the moving sidewalk. When it reaches the top of the staircase, it makes a turn, and is borne away to the left.

At this first meeting, the spectator has but a passing glimpse of the figures which are to play the principal parts in the story—he will examine them later one by one, here a general view must suffice.

At the head, the President with several exotic sovereigns (Asiaticprinces, African kings, in costumes half European, half Thousandand-one-Nights); behind them, gaudy ambassadors of every nation and every color, generals gilded and plumed, officers in various uniforms, Academicians, members of Parliament. The fair sex is represented in the procession by the wives of some of the dignitaries, by actresses, women of fashion, official beauties and other great ousels of the Tout-Cosmopolis, with various claims to celebrity.

The grouping shoidd make particularly prominent certain knots of people in the procession:—first the Master of the Machines, whose forceful originality shoidd immediately attract attention; near him his wife, his engineers and mechanics;—the Fair Ilortense and her little court;—the young Avetle with a group of gay young men;—lastly a few official figures: the old Academician Bicorncille, Agenor the Diplomat, etc.

The procession is borne away to the left by the moving platform, and makes the round of the Hall—now on the balcony level, now on the floor—so that it may have a comprehensive view of all the monstrous or grotesque machines.

It finally reaches the large stage, which fills the end of the Hall and overlooks it. It crosses the front of this stage to the extreme right, then by a half-turn lands at the foot of a platform, placed in the middle of the stage, on which are rows of seats. In the front row, sumptuous chairs for the President and the sovereigns. Other seats, less pompous, but also in the front row, for the Master of the Machines and the principal personages.

WHEN they are seated, the spectator sees, as through their eyes, the interior of the Ilall and the crowd, to right, to left, behrw, which vigorously acclaims them—then from below, through the eyes of the crowd, the stage and the official personages seated there— finally one by one, in close-ups, the faces of the story's protagonists:

1. THE PRESIDENT—a perfect nonentity, solemn and affable, with an eternal smile which never understands anything. But a thoroughly good fellow.

2. THE MASTER OF THE MACHINES—MARTIN PILON, whom his workmen call: MARTEAU PILON, and his detractors, "Pilon Marteau"—40 to 50 years old, at/detic figure. A powerful head, with over-accentuated features. In expression, energetic and febrile, at times strangely sarcastic and disdainful. In gesture, sudden, awkward, passionate. Great concentrated violence. We feel that he is devoured by passions, great and small. He lends himself to the ridicule of fools, but is never wholly absurd. Excessively nervous and full of subconscious electricity.

3. HIS WIFE, FÉLICITÉ—A fine woman, slightly heavy and square, no longer very young, rather badly turned out, with the air of a robust peasantwoman dressed up. She also causes smiles—from smart people. This does not disturb her in the least, whereas her husband suffers impatiently from it. She is a phlegmatic soul, with a good eye, a good tongue and good fists.

4. THE FAIR HORTENSE—a famous actress, tall, blond, opulent, splendidly be-turbaned and befeathered—fashion's queen and royally stupid. She takes part in all the ceremonies of the Machine Republic; she is an indispensable part of the furnishings.

5. The youthful AVETTE, called AVIETTE—18 or 20, sporting, laughing, without illusions, fearing nothing, respecting nothing; thinking only of a good time, quick, pliable, careless, imprudent, full of outrageous mockery. Her friend ROMINET, a young electrical engineer, favorite disciple of Martin Pilon, 20 or 25, he too, quick, gay, as intelligent and mischievous as a monkey.

6. A few types, slightly caricatured, in the next group: Academicians, Diplomats, Peacocks and Bucks.

The President ascends the platform, and reads the inauguration speech, which is projected upon the screen in a succession of emphatic paragraphs.

His discourse is a panegyric of Civilization, of Science, and of Human Thought, controller of Nature. As foil to the century of Light, the orator opposes the obscurantism of the past. He makes over, in his own way, the history of Humanity, heavily pitying our ignorant ancestors, who had to work so hard to accomplish the simplest ends. The President has only the most crushing irony for the old pastoral life.

Principal moments of the speech, to be thrown on the screen in caricatural images, emphasized by the following sentences:

1. HUMANITY, GENTLEMEN, HAS REACHED THE SUMMIT OF LIGHT . . .

2. AFTER EIGHTY-FOUR CENTURIES OF ARDUOUS CLIMBING FROM THE DEPTHS OF NIGHT AND ABYSMAL DARKNESS . . .

3. WHAT A CONTRAST, GENTLEMEN! . . . THERE BELOW, POOR CREATURES, HARDLY YET EMERGING FROM THE CLAY OF THE EARTH, GNAWING ITS BARK LIKE WORMS, WITH INFINITE PAINS . . . ABOVE, DEMIGODS, AUREOLED WITH GENIUS, SOVEREIGNS OF NATURE . . .

4. CONSIDER, GENTLEMEN, THE LAUGHABLE EFFORTS THAT MAN OF YORE HAD TO MAKE TO ACCOMPLISH THE SIMPLEST ENDS: TO WREST FROM THE EARTH HIS DAILY BREAD ...

(The old Adam, naked, is shown hoeing the hard soil, covered with thorns, with snakes and sharp stones—he stops continually to wipe away his sweat. . . .)

5. NEARER OUR TIME, THOSE COMIC OXDRAWN PLOUGHS, THE ANIMAL TRACTION SLOW AS TORTOISES, THOSE ABSURD TOOLS, THOSE ARCHAIC SCYTHES, THAT RIDICULOUS "PASTORAL LIFE" WHICH DELIGHTED OUR CHILDISH ANCESTORS . . .

6. TODAY . . .

(A great plain, which is being ploughed, seeded and reaped, with vertiginous rapidity, by machines controlled by a single man. lie sits in an observation tower, and nonchalantly bends his thinker's brow over a newspaper.

7. THE COURSE OF HUMAN PROGRESS IS LIKE A RIVER-AT FIRST HUMBLE, OBSCURE, WINDING, STONY-SEEMINGLY THWARTED AND BLOCKED-YET EVER BREAKING THROUGH THE OBSTACLES WITH SLOW PATIENCE-GRADUALLY QUICKENING ITS PACE, FASTER, ALWAYS FASTER, UNTIL IT CATARACTS, A FORMIDABLE NIAGARA, INTO THE RADIANT LIGHT . . .

8. AT THE BEGINNING: "TIIOU SHALT EARN THY BREAD BY THE SWEAT OF THY BROW."TODAY: "HE SAID, 'LET THERE BE LIGHT', AND THERE WAS LIGHT" . . . (The primates of pre-history and the modern Demi-God.)

9. SEE THE ULTRA-MODERN TYPE OF THE AMERICAN DEMI-GOD, WHO FROM HIS OFFICE CHAIR RULES THE SUN AND MOON AND THE ELEMENTS. AN ARMY OF MACHINES OBEYS THE NEGLIGENT PRESSURE OF HIS Fingers, As THEY PLAY OVER AN ELECTRIC KEYBOARD.

10. LET US DO HOMAGE, GENTLEMEN, TO 'Fins MAGNIFICENT SIGHT: MAN, KING OF MACHINERY! WE CELEBRATE TODAY HIS UNIMAGINED VICTORY, THE APOGEE OF FIUMAN PROGRESS AND HUMAN GENIUS.

DURING the speech we may watch various little scenes and incidents in the front row of the stage: The Fair Hortense flirts with her train of Snobs. The Master of the Machines cannot hide his ardent interest in the beautiful actress. Everyone notices it with amusement, but he is oblivious to this fact. His wife, Felicile, finally draws his attention to the smiles: he is filled with irritation of which we shall sec the effects shortly, as soon as his subconsciousness comes into play. For the present he continues to follow the proceedings, though continually distracted by his passion for Ilortense, by his jealous anger against her admirers, by his disdain for the whole assemblage; he shows this disdain all loo clearly, by snickers and shrugs at many of the asininities of the presidential speech. The Master of Ceremonies has to call him to order. The President, however, full of his written eloquence (which he reads with the greater gusto, that he probably did not pen it) does not notice anything:—he never does notice anything.

As he reaches the peroration, the President presses an electric switch, putting in motion the whole army of machines. (Cheers from the crowd.)

He then calls upon the Master of Machines who comes forward amid acclamations, happy to display his genius before this crowd that has been laughing at him, and above all before the Fair Hortense whom he hopes to charm. With a comprehensive gesture he presents to the audience the army of machines, and puts them through their drill. Series of manoeuvres. At a sign, this growling, roaring, turning, gesticulating army stops and is transfixed in deathlike stillness—then at another sign begins again to growl, to roar, to turn, to gesticulate. The Master seems a magician who can chain and unchain the elements. Great enthusiasm among the crowd—and especially among the Master's workmen, who are devoted to him. Flis pride swells even more, he assumes the attitude of a conqueror.

Ignoring the plebs, he motions to his friends to follow him, and leads them down to an empty space in the center of the Hall, where he marshalls the new machines for exhibition.

1. THE FORMIDABLY POWERFUL MACHINES. These, though docile and obedient, yet cannot be beheld without a shudder. One of them lifts an enormous mass and carelessly swings it above the heads of the honorable company. Another has a hundred arms of steel which stretch and uncurl on all sides like a gigantic spider.

2. THE PSYCHOLOGICAL MACHINE. The machine for reading tnoughts. It is built with an eye at the end of a trunk like an elephant's which it stretches out, placing one end on the patient's skull, while from the other end, like a moving picture machine, it projects upon a screen whatever it sees within the skull: The sleeping animal, the secret thoughts.—The Master of the Machines begins his experiments on rather uninteresting people of minor importance. Then, as he has been furtively watching the Fair Hortense, and sees with increasing annoyance that she is paying no attention to him, but flirting more and more outrageously with the Diplomat Agenor—he becomes furious and seeks revenge by exposing to the public eyes the silliness of their thoughts. He approaches them very politely, offering to try his little experiment, to which they unsuspiciously consent, for they have not been watching the proceedings.

The pictures should present the caricatural ideal that each person has of him or herself, accompanied by a symbolic figure which materializes the impression: Thus, for the Fair Hortense, we should sec "The Empress Ilortense", on the arm of one of the sovereigns present, of black or yellow skin—even of two, with a train of admirers: at the back, dominating the scene, a great peacock spreads its tail. For others, show a wcathervane, a turkey, a sleeper bound by spider webs, a scampering monkey, etc. And always, by the side of the symbol, some grotesque scene from the imaginary life of the person.

AT the very first experiments some of the spectators, terrified lest their thoughts be read, slip away into the background or hide their faces and hope to be forgotten. A few amiable and simple souls, on the other hand, come forward—for instance, one of the exotic kings.

The Master of Ceremonies is hard pressed to give a llattering interpretation of these insulting pictures. He endeavors to prevent any further experiments. To his sudden dismay the President comes forward as a subject. Flis followers try in vain to dissuade him; he insists. But the result is nil, the screen remains white with barely a few flickering shadows. There is nothing there. Slightly embarrassed amusement of the crowd. The Master of Ceremonies idealizes this impeccable nothingness— it symbolizes clearness and integrity, the zero is transmuted into the circle, emblem of perfection. The President still fails to understand and smiles blandly upon them all.

(Continued on page 90)

(Continued, from page 36)

WHILE the Master of the Machines is busy, his attention divided between the President and the Fair Hortense, Aviette, whose tomboy nonsense we have already noticed, is seized by a mischievous desire: she steals up behind the Master of the Machines and applies the receiver of the thoughtreading machine to the back of his head, Flashed upon the screen we see Marteau Pilon's feelings toward the audience, They are full of pride, antagonism and contempt. But his more personal feelings appear rather ridiculous: his vanity, for instance, and his passion for the actress. These pictures provoke such a shout of laughter that he immediately discovers the trick and puts a stop to it. But Aviette's indiscretion has added to the number of his enemies and greatly enhanced his own annoyance. In his irritation, he loses control of himself and his subconsciousness comes into play. It is the beginning of the Revolt of the Machines .

At first some harmless jokes—

The official ceremony being over, the procession takes its place again on the moving sidewalk. But instead of proceeding smoothly we see the sidewalk shake, reel, tip and heave, seeming to take pleasure in bouncing up and down all those grave and important people. By a sudden stop it sends into the air, with a real Nijinsky spring, the President and the whole procession. General indignation. The Master of the Machines rushes forward, turns off the power, argues excitedly with his workmen and acrimoniously with the officials, and excusing himself as best he can. Everyone is more and more irritated.

The procession continues on its way, refusing, however, to ride any longer on the moving platform. We follow the officials down the center aisle.

The machines continue their mischievous tricks. The long arm of one of them surreptitiously pinches the Fair Hortense in the back. She turns furiously and berates the old and most respectable Academician Bicorneille. Suppressed laughter from Aviette, Rominet and their little group and from the workmen, glances of amusement among the audienceBut he laughs best who laughs last! . . .

Quickly uneasiness and fear spread through the crowd. A rubber pipe creeps out and fastens itself like an elephant's trunk upon the nose of the polished Diplomat who has been flirting with Hortense. A metal pipe coughs a cloud of smoke into the face of the High-Marshal, who takes a wild leap backward. A selfsatisfied Dandy finds his coat-tails suddenly blown above his head where they spread like sails. One of the machines negligently sprays little streams of cement to right and left. Finally the President is snatched by a crane and carried far up into the air. As he dangles by the seat of his trousers, he still holds his hat high in his hand and seems, in his wild contortions, to be still bowing. The Master of the Machines pleads and storms at the machine; at the same time he is subconsciously so amused that he cannot help laughing at the grotesque poses of the President. It is the last straw—the indignation against him reaches the pitch of action. He is arrested, insulted, threatened, jostled and led off to prison. His wife seeks to defend him, but she is quickly pushed away. The workmen, who have been greatly entertained, show their sympathy for their master. He is led off, raging and shaking his fist at his enemies.

We see at the back of the picture the thoughts of vengeance and destruction which seethe in his mind.

The procession resumes its grave and measured goose-step—all the more solemn for its recent vexation, casting suspicious glances to right and left at the machines which have subsided into innocent quietude, broken only by an occasional muffled tremor. The procession goes out through the great door of the Hall, which is rapidly emptied. As the door closes upon the last of the audience, in the lessening light we see a shiver run through all the machines, from end to end of the empty building. For an instant only. When the guards at the doors turn at the sound there is nothing to be seen. The machines have resumed their immobility. Silence.

ACT II. THE REVOLT OF THE MACHINES. SCENE I. The Hall, dimly lit by occastonal electric lamps. The machines seem asleep.

Watchmen pass on their rounds. All is ® orderWhen they go out we see one of the machines begin to move, to stretch itself slowly and yawn. I hen anotherand another. Then the whole regiment of the machines.

A second patrol begins its rounds. The machines are instantly motionless. But they are on the qui vive. And suddenly the Patrol matched up and thrust into some giant maw, or converted into a block of cement.

At this exploit, which eliminated the presence of men from the building, a great tumult of joy shakes the machines hear the whistling, howling strident laughter and braying of monsters. We see a hundred steel arms stretch and bend, leathe belts begin to move, wheels to turn, boilers to steam, exhaust pipes to hiss. There is Pandemonium for a few minutes.

Then order is established. The machines begin their march, according to their size. They move against the walls of the Hall like battering-rams. Their formidable pressure quickly makes a breach. The bronze Pillars are shaken, the walls split, the windows burst and are pulverized. Through the opening we catch a glimpse of the starry sky, as the flock of monsters crawls forth into the night.

SCENE II. The spectator is transported to a square in the center of the city where several streets converge.

A city of colossal American sky-scrapers, which we see silhouetted against the moon-lit sky—among factory-chimneys and towers and one solitary churchsteeple. At one corner stands the prison in which lies the Master of the Machines.

The street-lights suddenly go out. Belated homegoers, groping in the darkness, are set upon by the vanguard of the machines. The little ones come first, running like street-urchins at the head of the procession. Some scurry like great rats, some attack like wild boars, some crawl, extending slimy arms from whose touch the terrified humans shrink in horror. Some fly heavily like bats

(Continued on page 92)

(Continued from page 90)

A panic-stricken crowd surges onto the stage, engulfing those who come from the opposite direction and sweeping them upon its tide. Behind it we hear the ominous clang of the sledge-hammers, the hard breathing of the engines, the footsteps of the great approaching monsters. We see the further houses tremble and sway: the church tower leans, totters and crashes to the ground. Then appears at the back, a monstrous machine —a tank-crane-excavator as high as a cathedral. The human crowd has not waited to see it, but has rushed away pell-mell with screams of terror. Not a human being is left on the scene. The gigantic machines appear, using elbows and heads to accomplish their deadly work. Behind them lies a field of ruins. The round moon shines upon this desert sweep which a few moments ago seemed an unshakable city of soaring buildings. And against the moon pass and repass the wings of many airplanes, turning, turning—

An instant more, and the machines begin demolishing the other corner of the square. They make a great gap in the prison wall. Through the breach emerges the Master of the Machines. He caresses the machines which have freed him, and attempts to subdue them, but they will not listen to him. They are off, and he runs after them.

The pictures follow the onward rush of the devastating engines, the Master at their heels, vainly calling to them to stop. Before them, the city crumbles, quarter after quarter, like houses built of cards.

SCENE III. Dawn—A hill near the city gates, from which can he seen the ruins and the surrounding fields. (This hill is the end of the mountain range which will later be ascended.)

The citizens, the President, his ministers, the officials and notables of Act I., have hastily sought refuge on the height, half-clad, and each clasping some object snatched up in the hurried flight. We recognize at once in the noisy, excited crowd, the President who, barefooted, but still in his evening clothes, clutches tightly his high hat in his hand: the Fair Hortcnse, who complains of the sun, of the dust, of the lack of proper consideration; Felicity Pilon already noticeable for her coolness, busy reassuring and stimulating, and beginning to gather about her a few capable lieutenants. Aviette and Rominet take it all as a joke, and laugh together at the burlesque turn of affairs: he is interested, too, by the problem of the machines in revolt, while Aviette's mischievous eyes miss none of the scenes of cowardly terror, of recrimination or of grotesque dispute which are enacted about her.

Among the people roam many escaped animals—oxen, donkeys, dogs and pigs.

The crowd watches breathlessly the last buildings of the City as they are annihilated: some great civic building, some great church seems to defy the destroyers' power for a moment, only to come crashing down in its turn.

We see the machines emerging from the fallen city into the fields which lie smiling in the morning sun-light: vast stretches of golden harvests, orchards, woods, lines of poplars by the river's banks. The riff-raff of little machines still heads them. Then comes the main army, with the monsters bringing up the rear.

Behind them we can discern the Master of the Machines and some of his workmen running, gesticulating desperately in a hopeless attempt to stem the flood. Some of the machines are seen to stop, to turn back and like dogs to sniff at his heels and harken to his voice. He tries to reason with them, but they quickly leave his side and run to resume their place in the crowd. The Master and his men then try to restrain them forcibly, but the machines turn wickedly upon them and put to flight the little group of men, barking at its heels until it reaches the foot of the hill. Marteau Pilon and the others scramble wearily and breathlessly to the top, where they arc greeted with invectives by the crowd.

Soon, however, the general attention is distracted by what is happening in the plain.

AFTER a few moments of hesitancy and uncertainty, the machines have decided upon the destruction of the whole countryside. And in this vast expanse each one goes at its own work with a devilish and fearful obstinacy.

The THRESHERS and REAPERS raze the fields of every stalk or blade.

The MECHANICAL SAWS cut down the trees at their roots and proceed to convert them into small discs.

The PERFORATORS are on a wild forage in search of walls of any description against which-they may ply their steel.

The CRANES stupidly take great jawfuls out of the earth and pour to the left what they have taken on the right, and then return to the right what they had put on the left.

The STEAM ROLLERS bring order and neatness by crushing everything.

The FIRE ENGINES work madly at drawing water from the river, sending it in great streams upon the banks, flooding everything.

The crowd of human beings on the hilltop can no longer contain its indignation, fury and terror. They shake their fists, scream, threaten, objurgate or fall upon the ground prostrated.

The general staff alone is calm and serene, sure that this vermin can be quickly swept away. Tanks, armored and bristling with guns, arc sent down into the plain. But when they reach the big machines, they are suddenly seen to stop, to sniff and hob-nob like dogs with the others, and finally to join their ranks. The soldiers are made prisoners, and the huge band regroups itself.

After which, all together, having shaved off every living thing on the plain, the machines begin their attack upon the hill—and the miserable human crowd, jostling and pushing, stumbles desperately toward the higher mountains in a maddened flight.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now