Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowRoyalty and a Caricature

ALDOUS HUXLEY

How Max Beerbohm Evoked a Journalistic Tornado With a Series of Cartoons

GREATLY, I imagine, to his astonishment, Mr. Max Beerbohm found himself, not long ago, at the vortex of one of those newspaper tornadoes which are periodically let loose for the devastation of public opinion. Not that public opinion is ever very seriously devasted. Those Gods of the Winds—or should they not rather be called Gods of Wind, tout court?—whose home is in Fleet Street, are too liberal with their hurricanes. Familiarity breeds contempt, and the newspaper reader walks through the howling whirlwind as serenely and unheedingly as though the barometer were set at Mild Breezes.

This particular tornado which, for the space of about a week, whirled furiously around Mr. Beerbohm, lo subside again, as all these winds of journalism do subside, as suddenly as it had arisen, was unleashed for reasons that seemed, goodness knows, queer enough even in England, but which must have struck the American mind as wonderfully fantastic.

It was an affair of Use majeste.

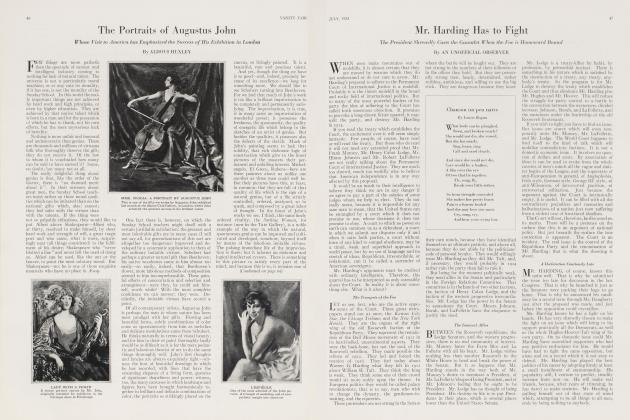

In his latest exhibition of caricatures Mr. Beerbohm had exposed a picture of the Prince of Wales—of the Prince of Wales as he might be expected to appear fifty years hence and after the English Revolution. Old Mr. Edward Windsor, who now lives very quietly in most respectable lodgings at "Balmoral", Lenin Avenue, Ealing, is shown in the act of espousing his landlady's middle-aged daughter. It was a charming drawing and a piece, it seemed to me when I saw it, of delightful and entirely inoffensive fun.

But that, evidently, was not how it struck the journalists. With a splendid unanimity the Gods of Wind uncorked their inflated bladders, and for days it furiously blew. Mr. Max Beerbohm was accused of bad taste, boorishness, disloyalty, calumny, Use majeste and, almost, blasphemy. The royal family, we were told, had been insulted, the throne bemuddied —goodness knows what else.

FOR the philosophic onlooker, the spectacle was not uninteresting. Not that there was anything about the press campaign itself that was in the least curious or remarkable—it was as stupid as any other press campaign. It was what the campaign represented. For genuinely, even after all the necessary discounts had been made, it did represent something. It really reflected—in a mirror, of course, that vastly magnified and distorted— the opinion of considerable sections of the English public. It voiced—through a megaphone—the feelings of those very numerous people in England who revere the royal family, as lien jonson loved Shakespeare, "this side idolatry"; and who feel that it is a piece of very bad taste, that it is all but blasphemy, to abuse or ridicule a member of the sacred clan. They would have us speak of royal personages as they would have us speak of the dead— nothing but good.

Now that this should be the case in Peru before the coming of the Spaniards, or in Constantinople before the coming of the Turks —or after it, for that matter—would be very comprehensible. For the Peruvian Inca was divine, a direct descendant of the Sun; the Emperor of Byzantium was the Viceroy of Christ and his successor, the Sultan, was Mahomet's representative on earth. The subjects of these potentates were brought up from earliest infancy to regard their kings as sacred beings. Loyalty was a tenet of their religion, and to lampoon the king was a piece of horrid blasphemy.

There were, moreover, purely practical and material reasons for behaving respectfully. The royal personage could have you drawn like a chicken, quartered at a moment's notice like a carcass of beef, if you did not. If you were a believer in Safety First, you spoke of your prince with nothing but the profoundest respect. It is surprising to what sincerity one can arise with the thumb-screw before him.

Turn the clock back four hundred years, and imagine Mr. Beerbohm poking fun, shall we say, at the son of Pope Alexander VI. Then, if you like, one might expect a fuss. For not only would the prince be called Cesare Borgia, Duke of Valentinois; but his father, the old Borgia, would be sitting on the throne of St. Peter, would have been chosen in conclave by the advice of the Holy Spirit, and would be the holder of those formidable keys which open and close the gates of Paradise. In ridiculing, however mildly, the first-born son, however natural, of God's vice-regent upon earth, Mr. Beerbohm would have been risking an act whose consequences might have been serious, not merely in this world, but throughout all eternity.

But this is mere fancy. In point of fact the clock still stands at 1923 and Mr. Beerbohm has done no more than make a little joke about the marriage of the heir to an extremely constitutional monarchy. He runs no risk either in this or the next world. For the king of England has little or no power over the bodies of his subjects; and though by law he is head of their Church, he is no Pope to bind or loose the soul; he is no worshipped Inca, no deified Emperor of Rome. The English monarchy today is one of those up-to-date, hard-working, hand-shaking monarchies which seem to be the only ones that manage to survive in democratized Europe. And yet the fact remains that Mr. Beerbohm's joke did strike large numbers of English people as being slightly risque, a little blasphemous. It seems, paradoxically, that the monarchy is more religiously revered now that it has no temporal power and lays no claim to spiritual authority, than when, in the past, it claimed a divine right to bully its subjects as much as it pleased.

Read, for example, what contemporary satirists wrote of Charles the Second—or rather don't read, for the process as I know by experience, having once devoted long months of my life to this sort of thing, is really rather a waste of lime—wrote, that is to. say, of a king who really did rule his country and who had a whole bench of Bishops to say that he did it by divine right.

"Dunkirk was sold; but why we do not know, Unless to erect a new Seraglio—

says one anonymous writer, for example. And the poet Andrew Marvell, more indignantly and, for the nonce, less wittily, protested that it was a shameful thing "To see Deo Gratlas writ on the Throne,

And the King's wicked life say: God there is none."

George III was mercilessly handled by the caricaturists and the pamphleteers. As regent and as king, his son was ridiculed and abused in a manner that would now be considered wholly outrageous. It would be easy, but tedious, to show that even the most absolute monarchs, even Popes, have been regarded as fair game by the pasquinaders of past ages.

IT may be objected that most of the monarchs of the past deserved all the ridicule and all the denunciation that they got, and that the present royal family of England does not. Those were bad; these are good. But to that we would answer that even the blameless Prince Albert, during the first years of his marriage while he and Baron Stockmar were gradually taking into their hands the reins of government, was treated very much more rudely than Mr. Beerbohm, who was not rude at all, has treated the Prince of Wales.

And yet he has been abused for his little joke with a show of righteous indignation which nobody, except those whose interest it was to feel it, felt towards the caricaturists of George the Third or the satirists of Charles the Second. We can only conclude that, with the decay of the royal power, there has been a corresponding increase in the reverence felt for the throne. At first sight, as I have said, this seems paradoxical. But when we come to consider the matter more closely, we shall find that this process is altogether in the natural order of things. For it is obvious that a king who really does rule his people must be held responsible by them for the effects of his rule. And since in the nature of things no government can satisfy the desires of all the governed; since, indeed, a ruler must consider himself lucky as well as virtuous if he can content even half his subjects, it is clear that a king who is really the head of the government will have to put up with a good deal of unpopularity. Not even a monarch can expect to get something for nothing; the joys of power have to be paid for with the sound of complaints and curses, with abuse, denunciation and— most galling because so hopelessly unanswerable—ridicule.

(Continued on paqe 114)

(Continued from page 44)

CONVERSELY, the sorrows—the boredoms, rather—of political impotence have their pleasing compensations. A monarch who does not govern is not held responsible by his subjects for the discomforts which almost every act of government must inevitably bring down upon some of them. So it comes about that what a constitutional monarch loses in power, he gains in respect and popularity. Ceasing to be the ruler of his country, he becomes, in a curious way, the symbol of it. And since to the human mind, which finds abstraction difficult and does not feel at home among entities on a more than human scale, a concrete symbol is something welcome and satisfying, it follows that the man who contrives to symbolize in his own person the whole national idea possesses a real importance, even though he may have no power or direct authority. Like the flag, like the national colors, the national heraldic animal or totem, the national anthem, the national allegoric personification, he becomes a simple and convenient sign for an idea immensely large and complex.

It is one thing to abuse the head of the government: even in these days of almost excessive politeness, the prime minister gets duly lampooned and caricatured. It is quite another thing to make fun of a national emblem. There are countries where you can get arrested for not saluting the flag; and I remember, in the Piazza at Venice, seeing an unfortunate individual, who remained seated and who laughed while the Italian anthem was being played, so mercilessly drubbed by the Fascists that he must have been thankful when the (>olice closed round him and dragged him off to jail. Nobody can afford to laugh at an emblem. By a British subject, Britannia must be represented as Bernard Partridge has been representing her, weekly, for the last how many years? in the pages of Punch—as an infinitely respectable Greek goddess of the dullest and most classic period. A royal family which has become a national symbol must be treated with the respect due to all such sacred emblems. Mr. Beerbohm made the mistake of treating a member of our symbolical House of Windsor as one might treat the head of a government—humorously. The burgesses of England, who revere that House because it convenient!}" symbolizes not merely the Empire but also themselves and their ideals, resented it.

Americans, I know, find it difficult to understand how this effete "king business" contrives to go on in England. It goes on primarily, of course, because we are an exceedingly conservative people, tenaciously attached to our old customs even when they are most palpably absurd. It will be hundreds of years beforeEngland ceases to measure in rods and perches; to weigh with ounces that vary according to the material weighed; to calculate quantities in terms of firkins, hogsheads, cords, chaldrons and kilderkins. It will also, I trust, be hundreds of years before England ceases to be a monarchy. For constitutional monarchy is an institution which, besides being respectably old, is also of great political value. We have arrived at it in England gradually, and as it were unconsciously. But what we have devised more or less by luck and accident, a Machiavelli, I am convinced, would have invented by the light of reason as being, in the circumstances, the most subtly perfect form of government imaginable. A state which possesses a nominal head, who does not in fact govern, possesses a permanent living symbol of itself to which its people can pay an unmixed devotion such as no real ruler can hope to have paid to him. To any government there is always an opposition. But government and opposition alike profess to have the interests of the country at heart; they differ only in their methods of serving these interests. The king who does not rule—who stands apart from the government and all its acts—is a living symbol of those national interests, like the country's flag—but more useful, because human and alive.

IN a small community, such as the city states of ancient Greece or mediaeval Italy, a symbolical figure of this kind is superfluous; the state is small enough for every citizen of it to be able to realize it completely and to feel a direct local patriotism towards it. But a great modern state is too large to be realized as a whole and directly felt for in this way. But if you can make one man into the symbol of the national idea, you at once endow your large state with many of the advantages belonging to the small one. For a direct local you substitute a direct personal patriotism. The human symbol can be sent round the great state to shake hands and, so to speak, to collect for the central authority the necessary tribute of personal patriotism. In the collection of this tribute the members of the House of Windsor work with an industriousness which I, for one, would be sorry to imitate. Poor symbols! Let us all be thankful that we stand only for ourselves.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now