Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

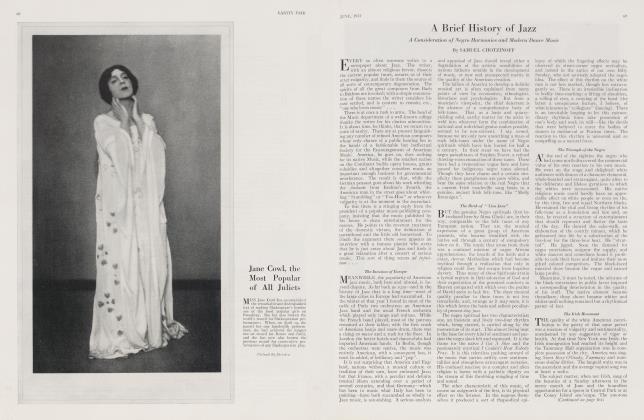

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowDramatic Expressionism in Practice

How the Expressionist Tells the Story of Mankind

ERNEST BOYD

WHEN one turns from the theory to the practice of Expressionism, one begins to understand, not perhaps the vagueness of the theories, but why they are vague. As I have pointed out in a previous article, the poetics of Expressionism lack simplicity. Some declare that Expressionism is movement, "for the word is movement, and in the beginning was the word". Others contend that Expressionism "sets content above form. It turns form into content. The external is intensified, and the elemental triumphs." Finally, there is the exhortation to "cast to the winds motives, logic and justice, write plays full of illogical surprises, of unjustifiable circumstances."

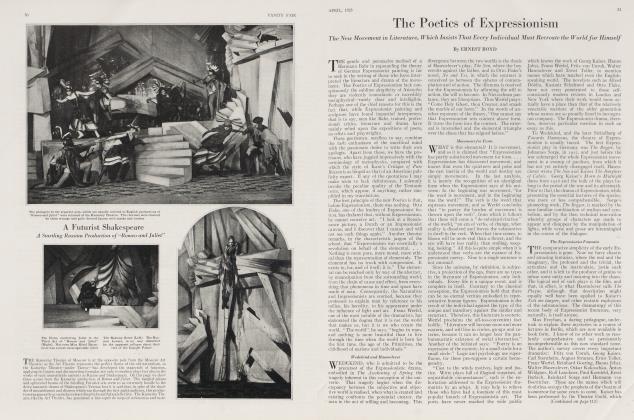

Those who have tried to reconcile such theories with the specimens of Expressionist drama which have been shown in New York will probably have wondered whether, after all, Georg Kaiser's From Morn to Midnight, Elmer Rice's The Adding Machine, John Howard Lawson's Roger Bloomer, realize the full intention of this particular form of dramatic art. The truth is, they do not. They represent a step further than Eugene O'Neill's The Hairy Ape in the direction of Expressionism, but the American theater has yet to see this form of drama in its purest and most logical expression. Georg Kaiser's Morn to Midnight represents merely a stage in the evolution towards Expressionism of a dramatist who had previously established his reputation in other forms; and his case is, to that extent, comparable to Eugene O'Neill's. Mr. Rice is more advanced in his technique—Mr. Lawson considerably less so—but in order to realize the distance which lies before them, one must compare them with the younger German dramatists.

A Generation Bom in Expressionism

THE complete Expressionist in literature belongs to the generation that was just becoming articulate when the great war began: the poets, Ivan Goll and Alfred Wolfenstein; the novelists, Kasimir Edschmid and Alfred Lemm; and the dramatists, Walter Hasenclever and Oskar Kokoschka. Here we find the new technique almost untrammeled by the old conventions; and, in consequence, a literature which started at the point where the later converts to Expressionism, and its disciples outside Germany, usually stop. The outstanding figure in this group is Walter Hasenclever, poet and dramatist.

Hasenclever has written a thumb-nail sketch of his own career, which is so characteristic that it is worth quoting: "I was bom on the 8th of July, 1890, at Aix-la-Chapelle, where my name is still anathema. In the spring of 1908 I was graduated, went to England and studied at Oxford. There I wrote my first play, and won the cost of printing it at poker. In 1909 I was in Lausanne, and afterwards came to Leipzig." There he came into contact with a group of the younger writers, and "soon surpassed his masters". Then he went to Italy and "frequented doctors".

In 1913 his first book, a volume of poems, appeared under the title of The Youth, followed, in 1914, by his first drama, The Son. He served in the war as "interpreter, caterer and kitchen-boy", and wrote out of those experiences his second book of verse, Death and Resurrection. A year later he published a pacifist tragedy, Antigone, which was followed by Mankind, The Saviour, The Decision, Beyond and The Plague. Of all these only the last-mentioned has appeared in English, a few months ago in The Smart Set. It is described by the author as "A Film", and has been seized upon by the critical opponents of Expressionism as the logical culmination of Expressionistic drama.

The Revolt of the Younger Generation

BEFORE jumping to that rash conclusion, however, let us see what Walter Hasenclever has accomplished within the limitations of the drama proper. Most of his plays have been produced in Germany, and they have aroused considerable interest and discussion. His work for the theater, therefore, is not theoretical but practical; and as it shows, at its best, the highest achievement of the Expressionistic drama, the claims of the school may fairly be tested by it.

His earliest important play was The Son, a five-act drama, which has acquired in Germany the significance of a manifesto; Its theme is essentially that of the whole philosophy of Hasenclever's generation, the revolt of youth, the conflict of father and son. Out of the simplest situation, the rebellion of a son against parental authority, the dramatist has made a play of remarkable intensity and technical originality. The plot merely follows the adventures of a young man who fails in his examination, defies the tyranny of a stem oldfashioned father, is initiated into the ways of physical love by an expert, is recaptured by the police and, grown conscious of his own identity by experience, resolves to murder his father, but is saved from parricide by the latter's sudden death during their supreme altercation.

The novelty lies in Hasenclever's development of the various situations. Thus, when the Son contemplates suicide and asks his tutor to leave him alone, the latter asks him what he proposes to do. " Indulge in a soliloquy ", he replies. " There was a time when this was laughed at, but I have never seen any harm in kneeling to my own pathos." Again, when he recites the long verse monologue on suicide, the author reminds us, through the mouth of one of the characters, that the Son has just plagiarized Faust. There is a consciousness of the art of the theater in the characters themselves which gives a peculiar quality to the scenes. In moments of exaltation the verse form is used, and music plays an important role, as when the Mephistophelian' figure of the Son's Friend entices him to freedom with the assistance of the Ninth Symphony. The song of the Marseillaise, in its turn, is employed when, on Freudian principles, the King becomes a symbol for the Father and this drama of the Œdipus complex moves towards its climax.

Hasenclever's Mankind, a drama in five acts and twenty-two scenes, is the most perfect example of Expressionist drama. In it are found all the elements of the new technique and almost nothing of the old, neither of the realistic nor of the romantic theater. Intense, colorful and with a powerful dramatic unity, in spite of the apparent incoherence of theme, which is nothing short of the life of man, this play passes over into the domain of the cinema but transcends the art of the screen.

Unlike The Plague, it is not a film; it is a stupendous drama. In inverse ratio to the verbosity of the theories of Expressionism is the brevity, the taciturnity of its best poetry and drama, and in this respect alone Hasenclever's Mankind is remarkable. One word or two, seldom more, is all that each character contributes to the dialogue. Yet, there is no painful effort required to supply the missing logical and conversational links to complete the sense. Hasenclever does not set down his ideas in a series of ill-digested lumps, to which one must give shape by dexterous ingenuity. The superfluousness of verbal realism on the stage has never been so effectively demonstrated.

In order to appreciate this peculiar feature of the play, quotation is necessary, and to that end a brief synopsis of it is indispensable. The scenes move from a cemetery to a cafe, then to a gambling-den, to a fortune-teller's, to the study of a specialist for venereal diseases, to the opera, to a maternity ward, to a court-room and to a madhouse. The action takes place among gamblers, thieves, prostitutes, criminals; in the world we live in, and outside of time and space.

The Expressionist's Story of Mankind

AS the play opens, Alexander, the central character, returns from his grave to the world, to atone for all the suffering he has caused during his previous existence. When he encounters a man who declares himself a murderer, Alexander takes from him a sack containing the victim's head, and the murderer descends into the grave. Henceforth Alexander goes through the world on his journey of expiation and atonement bearing with him this sack as a burden and a warning. First he becomes a waiter, and then he appears in different forms through the twenty-two scenes which lead him back to the grave. There .he can return only when some sacrifice is made for him, as he himself assumes the guilt of the unhappy in each place through which he passes. Finally the murderer rises from the grave and gives his place to Alexander, from whom he receives back the sack, now empty as a sign that the work of atonement is complete.

The outline of such a play cannot be given, because the dramatist himself has reduced it to elementals; and its scenes are the whole panorama of human life and yearning, of civilization and its institutions, of poverty and vice. Each phase of existence has its type, made visible in essential outline, and speaking only the key-words of the character. The gambler cries "bank", the worker "strike", the prostitute "silk", humanity "money", and the judge "death sentence". Through this chaos of passions and suffering goes the seeker with outstretched arms, crying "Love", "Who am I?", "I seek myself", "I willatone", "Allare murderers."

(Continued on page 118)

(Continued from page 58)

A typical scene, illustrating the rapid juxtaposition of the real world and the imaginary world exteriorized, is the opening of the fourth act. It will be noticed how, apart from stage directions, inanimate objects become part of the dramatis personae, the moaning of the wind, the blare of a trombone, and in the scene that follows, the clock striking and the darkening of the room. The r6les played by lighting are many throughout the piece, and are not to be confused with the scenic settings indicated in italics.

STORE-ROOM: A bed. A candle on the night-table. A wall in the background.

AGATHA (unhooks her dress, lets down the braids of her hair, takes notepaper, writes.

A VOICE: Festive evening!

AGATHA (folds the letter, smiles and lakes it with her to bed. The candle flickers).

AGATHA: Beloved!

A VOICE: Clean the boots!

AGATHA (starts up, takes her dress, sews. She smiles, presses the letter to her lips, grows pensive and weeps. The candle flickers. Tire dress falls to the ground).

AGATHA (falls asleep. Thewall disap pears and a landscape is visible. Stars in the sky. The candle flickers out. The sun and the moon rise).

ALEXANDER (stands on the edge of the horizon).

AGATHA (opens out her arms): Come to me!

ALEXANDER (comes straight through the landscape to her bed).

AGATHA (hands him the letter).

ALEXANDER (sits on the bed,)-. Do not cry!

AGATHA: Lilac. (The trees bloom.)

AGATHA: The wind is stirring.

ALEXANDER (caresses her). Butterfly!

THE CLOCK STRIKES

ALEXANDER: My fate.

AGATHA: I will follow you.

ALEXANDER (smiles): Child!

A star falls into the sunny landscape.

ALEXANDER: Everything is changed. (Kisses her. The landscape disappears. The wall becomes visible. Alexander is gone. The candle is still burning.)

AGATHA- (awakes).

A VOICE: Time to get up!

The candle flickers.

AGATHA (jumps out of bed, runs to the press, takes out a spray of artificial flowers, and presses it to her breast): Spring!!

THE STORE-ROOM GROWS DARK.

The landscape again appears. Now it is gray and commonplace.

ALEXANDER (awakens from his sleep on a bank, finds the sack, looks at it questioningly).

THE fourth scene in the same act is one of the niost striking examples of Hasenclevejr's skilful use of key-words, and his power of achieving the maximum of dramatic effect with a minimum of dialogue.

TRIAL BY JURY

To the left the bench, the Presiding Judge. In front of him a desk with the State's Attorney. In the background, the Jury. On the right, spectators: The Hotel Proprietor, the Customer, the Gentleman, the Prostitutes, the Beggar, the Newsboy, the Theater Attendant. In the foreground, against the press, Agatha. In front the seat for the witnesses: the Old Waiter. In the center, on the table, the Head. Beside this, on a chair, Alexander.

PRESIDING JUDGE (holding the sack in his hand): The head proves it.

THE BENCH OF JUDGES (nods). PRESIDING JUDGE: Accused! ALEXANDER ((looks up).

PRESIDING JUDGE: Are you guilty? SHOUT: Murderer!

AGATHA: NO!

PRESIDING JUDGE: Silence!

THE OLD WAITER (raising his finger):I swear.

PRESIDING JUDGE: "SO help me God . . ."

THE OLD WAITER: Amen.

PRESIDING JUDGE: The State's Attorney!

STATE'S ATTORNEY (rising): Supreme tribunal!

JURY (stand up).

STATE'S ATTORNEY: Human life has been taken.

ALEXANDER(looks at him).

STATE'S ATTORNEY: An eye for an eye. THE PUBLIC (leans forward).

STATE'S ATTORNEY: Death sentence. (Sits down.)

PRESIDING JUDGE: The accused! ALEXANDER (remains silent).

PRESIDING JUDGE: Consider your verdict.

The bench and jury retire. The courtroom grows empty. Agatha and Alexander remain alone.

ALEXANDER (turns around and sees Agatha).

AGATHA (smiles): I follow you. ALEXANDER (is bewildered and clutches his forehead).

AGATHA: I love you.

The courtroom fills. Bench and jury return.

THE GIRL (comes in among the spectators. She is starving and holds her child to her breast).

PRESIDING JUDGE: In the name of the King! (All rise.)

FOREMAN OF THE JURY: Guilty!

THE GIRL (holding up her child to the room). Hunger!!

INSPECTOR (pulls her back).

PRESIDING JUDGE: Condemned to death.

All resume their seats.

READ imaginatively, such scenes at once suggest the immense opportunity for the producer and the scenic artist in Mankind. Obviously, plays of this type should be seen in the theater rather than studied in the printed page, where the typographical devices of the author can barely hint at his intention. The second scene of the second act, for example, begins thus:

THE ROOM GROWS LIGHT THE GIRL: I am frightened.

THE YOUTH (gets up).

THE GIRL: It is coming closer.

THE YOUTH (goes to the door).

THE GIRL: Something is happening! THE YOUTH (opens the door).

THE GIRL: NOW.

BELOW A CHAIR FALLS THE GIRL (screaming): Someone has died!!

THE YOUTH (runs dozen).

THE GIRL (falls backwards in a swoon).

Here is obviously an ingenious adaptation of the method of the early Maeterlinck of L'Intruse, the creation of an atmosphere of suspense and terror by means of the simplest effects. Frequently Hasenclever reduces an important episode to a few stage directions, as in the close of the gruesome and extraordinary scene at the doctor's, towards the end of the second act. The young man has had sentence of death pronounced upon him, and the girl has opened a vein in her arm to escape unmarried motherhood.

ALEXANDER (opens the closet door on the left).

MOONLIGHT

THE YOUTH (lying on the ground). ALEXANDER (touches him).

THE GIRL (comes nearer).

THE YOUTH (stands up. A skeleton with a death's head).

ALEXANDER (takes him by the hand. They go off).

(Continued on page 120)

(Continued from page 118)

As I have already stated, hostile critics regard the cinema as the logical goal of Expressionistic drama; and when Hasenclever described The Plague as "a film", they rejoiced in their own wisdom. Mankind, however, must be regarded as the vindication of his method, for here is drama which, while calling for the producer of genius and imagination, nevertheless derives its essential interest from the living humanity of its scenes and characters.

In its frank recognition of the fact that, in writing for the theater, the barest indications are sufficient to secure effects which can be described only at the cost of many words, the play is an interesting revolt against the opposite tradition as elaborated by Shaw and the dramatists of that school. Clearly there are limits

to this method, and Hasenclever himself did not attempt to express the drama of The Son in brief notation. Even if Mankind be regarded as a scenario, it would mark an important advance for the cinema which has not taken kindly even to that elementary form of Expressionism associated in the popular mind with the angular fantastic settings and irregular lines of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari.

As it is, however, Walter Hasenclever has made a real contribution to the Expressionist theater. He has kept strictly within the limits assigned to this form of drama by the theorists, and he has achieved the perfection of its special technique. Until Mankind has been seen on the American stage we may refrain from wasting our astonishment or our indignation upon lesser wonders.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now