Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowGolfing Luck

Wherein is Argued the Uncertain Truism that Fortune Favors the Brave

BERNARD DARWIN

I HAVE often felt very sorry for chess players. I do not myself play their game, though I have often read with awe the usually unpronounceable names of their champions. I am sorry for them because they can never talk aloud about their opponents' luck. Alone among games, theirs is—as I understand the matter—utterly inexorable, irredeemably logical; there are no bad lies, no bunkers jumped, no long putts: the best man always wins.

And yet, though I have not the honor of knowing any chess champions, I would wager that they do sometimes in their secret hearts complain of their own or the other fellow's luck. If it had not been for the most pestilent fortune, they would have foreseen that trap that was being laid for them; an unlucky something distracted their attention perhaps at the critical moment. I do not know exactly what form their excuses take, but, being human, I am sure that they cannot altogether dispense with cursing their luck.

Naturally, then, we golfers—whose game, thank Heaven, is not like chess, but is capable of all sorts of "breaks"—not only think, but talk a good deal about luck. And what nonsense we do talk about it, nonsense that makes us blush hotly, when the first intolerable sting is past.

The Vagaries of Fortune

IT would be pedantic to allege that there was no such thing as luck in golf. We all say that no one can hope to win a big competition unless the luck is running with him, but it is hard to define exactly what we mean. That precious something which we call the "run of the green" is for the most part impalpable. If a bunker yawns between me and the green; if I take a mashie niblick, thus advertising my intention of playing a high pitch; if I thereupon hit the ball hard along the ground, and the ball, taking off at exactly the right spot, leaps over the chasm and lies dead at the hole, then I cannot be heard to deny that I was lucky. If you—my adversary—having played the ideal tee-shot down the center of the fairway find the ball at the bottom of a deep hoofmark, I may rejoice exceedingly, but I cannot but admit that you have been unlucky.

But most bits of luck, one way or the other, are not thus obvious. It is generally held to be lucky if a man continually holes his putts at sixty feet, but this is, strictly speaking, indefensible; he has only done what he intended, only made a series of the most perfect imaginable strokes. When two years ago Jock Hutchison won our open championship at St. Andrews, he had what was generally called a wonderful slice of luck. At the short eighth he holed his pitch for a one and then at the ninth, which measures nearer three hundred yards than two, he very nearly did another one. No doubt, in ordinary language, he was lucky: yet he made one perfect shot and another so nearly perfect that it might cogently be argued that he was unlucky, in that the second tee-shot did not hole out as well as the first.

Accidents of this delightful description are of no use, unless one is man enough to take advantage of them. The supreme value to Hutchison of those two holes in three strokes lay in the time of their coming. He had not made a promising start, and being a very human as well as a very great golfer, he wanted a little fillip. Those two holes gave it to him and sent him away with a "streak" of winning golf.

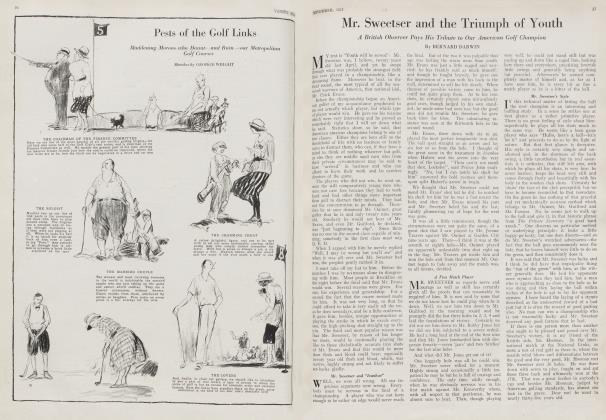

Somewhat similar was the piece of good "luck" (I put it deliberately in inverted commas) which befell Mr. Sweetser in his match with Mr. Bobby Jones at Brookline last summer. Here was a match that was bound to be a fierce one, with both players wrought up to a high pitch; and at the second hole Mr. Sweetser played a perfect pitch, and the ball went in for a two. Mr. Jones played what, in everyday inaccurate language, was an equally perfect shot, but of course the ball did not go in—such things cannot happen twice— it stayed three or four inches outside. Then away went Mr. Sweetser with unbeatable golf, while his adversary made mistakes, and was six down at the turn. Did that one shot make only the difference of one hole, or of most or all of the half dozen? No one can say. All that can be said is that Mr. Sweetser made the very best possible use of an incident likely to be crucial.

The Favored Sons of Chance

THE people who get the reputation of being lucky golfers are those who can use their luck. They are invariably, in my experience, bold players who go out envisaging victory, believing whole-heartedly that it is in mortals to command success. Of all the great players of my own time, one had pre-eminently the reputation of being lucky. This was the late Mr. F. G., or, as he was always called, Freddie Tait. And of all golfers he was the most quietly confident. He went out to a big match as to a bridal. He might and did play bad shots, but he never played timid ones; he was always giving himself a chance; and it must be admitted that Fortune did seem to favor his bravery.

I remember two particular instances. In the semi-final of the Amateur Championship at Hoylake, in 1898, he beat Mr. John Low at the twenty-second hole. In order to do that, he laid one very long brassey shot practically dead at the sixteenth. He holed one very long putt to save his neck at the twentieth, and put another brassey shot which kicked inwards from the pitch, quite close to the twenty-first, after hooking a really dreadful tee-shot out of bounds. Small wonder that Mr. Low took three putts at the twenty-second. Flesh and blood could bear it no more.

And then Mr. Tait went on to Sandwich to play for the St. George's Vase, which is our biggest amateur scoring competition recently won by Mr. Ouimet in impressive fashion. He was playing with Mr. Mure Fergusson, whom he had just beaten in the final of the Championship, and the prize lay between the two. All day long Mr. Fergusson had struggled along behind, and at length victory seemed in his grasp. At the thirty-sixth hole, with the scores level, he was lying a yard away in three; and Freddie, also in three, was away over the green, so close to the fence that he only just had room to take his club back. What did he do but hole out over hill and dale, and poor Mr. Fergusson missed. I do not wonder, for it was truly heart-breaking. That was the sort of thing that Freddie Tait seemed always to be doing, and I think he did it because he always contemplated doing it, and refused to allow the word impossible in his golfing vocabulary.

Snatching Victory from Defeat

OF present-day players, Mr. Tolley has something of the same capacity for redeeming errors by amazing shots at the last moment. Mr. Welhered tells a little story of him which is characteristic. The Oxford University Club was playing for some medal of no great importance. The play was nearly over, and several people were practising putting on the home green. To them arrived a caddie with a message. Mr. Tolley had one shot to tie for the medal (a tee-shot of 240 yards) and he could not imagine how he could be expected to hole that shot with so many idle persons clustering round the pin. He did not in fact hole it, but he was taking 710 chances; he meant to, if he could, and that is the frame of mind that produces, now and again, the shots that take the spectators' breath away and snatch lost matches out of the fire.

If it is the brave men who get called lucky, the reverse does not always hold good. There are some who are called unlucky golfers, and they certainly do not lack bravery. The most conspicuous of these is that wonderful veteran Sandy Herd, who now, at the age of 54 or 55, is playing away with all the skill and fire of youth. Sandy has only won one Open Championship, and that does no justice to his great powers. He has had several others apparently in his grasp, and they have eluded him at the last. No man is a more gallant and courageous fighter; you cannot damp his spirit by disaster. What he lacks just a little, I think, is the power of bearing prosperity. He cannot look dour when things are going well, and he has been sometimes in just too much of a hurry to snatch the victory and be done with it, instead of waiting for it.

(Continued on page 102)

(Continued from page 71)

Leaving Champions on one side and coming down to our humble selves, it is very hard in certain circumstances not to be a fatalist about golfing luck. For instance, there is the matter of how a ball lies in a bunker, which may make all the difference in the world. You—my enemy —play the odd, and deposit the ball in that deep bunker in front of the green, Humanly speaking, I have only to get over to win the hole. Therefore, I lift prematurely an over-anxious eye, and plump! in goes my ball to join yours, As we walk after our shots I know only too well what we shall find. One ball will be at the bottom of a heel-mark— that will be mine; one will be lying on a smooth and friendly upward slope—that will be yours. And, sure enough, that is what happens, and I deserved it. The particular Fate that looks after golf is, as the small boy described the famous headmaster "a just beast". It is much the same when you are lying twenty feet away from the hole, and I have to play the like. If I lay my putt dead, I know you will miss yours; but I am too cautious and am short. Now all is lost. I know that you will hole yours, All too soon I hear the deadly rattle of your ball against the tin. Justice again, of course; but a cruel justice. People talk of cards being unforgiving, but their ruthlessness is nothing to that of the golfing Fates.

And then, of course, there is the matter of stymies. They seem to pursue us on certain days, with a causeless vindictiveness, but if we think it all over afterwards in cold blood, some of them at least were partly our own fault. The days on which we are stymied are seldom: those on which we are putting are very well. We are leaving our ball some little distance from the hole with our approach putts, and into the space so left the other little beast of a ball insinuates itself, However, this is a dangerously cpntroversial topic. I have one friend in Boston who, should he chance to read this, would at once overwhelm me with statistics of all the stymies that were laid in all the chief tournaments in America during the last year.

Fortune, as I said, favors the brave in golf, but I am not brave enough to play her at the game of statistics. I know she has me beaten.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now