Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowA Recollection of Cesar Franck

A Sketch of the French Master by His Favourite Pupil

VINCENT D'INDY

This article forms the introduction of M. d'lrtdy's edition of the "Piano Compositions of Cesar Franck", and is reproduced by courtesy of the Oliver Ditson Company, publishers of the Musician's Library, The translation is by Mr. Charles F. Manney.

AT the very period when the giant of the symphony, Ludwig von Beethoven, was completing the manuscript of that one among his works which he himself considered the most perfect,— I speak of the sublime Messe Solenndle in D major,—on the tenth of December, 1822, there was bom at Lidge the one who was destined to become in the symphonic succession, as well as the realm of religious music, the true descendant of the Master of Bonn.

It was in the country' of the Walloons that Osar Franck was bom—in that country, so akin to France not only heart and language, but even in external appearance. For what is more similar the French central plateau than those valleys broken by abrupt and picturesque plains, where in the spring the golden broom spreads out to an almost unlimited horizon; or those low, rounded hills, where the French traveler finds again with surprise the beeches and pines which are native to his cold CSvennes Mountains? It was such a country, Gallic in aspect, German in customs and surroundings, which was destined by fate to cradle the genius who should create a symphonic art that was French in spirit, clarity and form; but firmly grounded, on the other hand, upon the noble Beethoven tradition, and nourished still further by the great inheritance of classic art.

FROM his earliest years, the mind of CSsar Franck was turned toward music. His father, a man of stem decision, had resolved that his two sons should become musicians, and they could not do other than bow to his will. Fortunately, the outcome of this premature determination was not that which is so generally the case; for too often it leads the child to an increasing dislike, if not to actual hatred, of the career undertaken without considering his preferences. With C6sar Franck, the musical seed fell upon a soil well adapted to make it grow and bear fruit.

At the age of twelve, he had completed his early studies at the music school of his native town, and his father, desirous of seeing him succeed in a larger field, left home with his two sons in 1835, and established himself in Paris. There C&ar commenced and made considerable progress in the study of counterpoint, fugue, and composition with Reicha, who gave him private lessons. The following year, however, Reicha died, and the father of the future composer of Lcs Beatitudes sought admission to the Paris Conservatoire for his son; but, nevertheless, it was not until 1837 that the boy was received as a pupil in the class of Labome for composition, and in that of Zimmermann for piano.

In 1842 (April 22) there came an order from his father, which forced Cfear to leave the Conservatoire: he was instructed to take up the career of a "virtuoso". It is during this period that most of his compositions for piano alone originated—arrangements for four hands, brilliant transcriptions, fantasias on themes of Dalayrue, and upon two Polish melodies—all such productions as formed the luggage then customary of the "composer-pianist".

But in spite of this forced labour, to which Franck was condemned by paternal authority with the practical aim of replenishing the family coffers, he could not restrain himself—genuine artist that he was—from searching for and finding, even in his most insignificant productions,' novel patterns which, though not in any way the aesthetic forms of serious coniposition, did involve new uses of the fingers, formulated designs hitherto unemployed, and distribute! the harmonies so as to give, to the piano a sonority never before heard. Thus it may be said, without comparing them to the works of his later manner, that certain of his early piano compositions possess a unique interest which may tempt musicians, and especially pianists, to study them. For instance, I may mention the Eclogue. Op. 3, and the Ballade, Op. 9, without including the trios for piano, violin, and violoncello, Op. 1 and Op. 2, which deserve particular mention.

Franck composed these first three trios while still a student at the Paris Conservatoire, and his .father had directed that he should dedicate them to H. M. Leopold I, King of Belgium. If I remember rightly a conversation which I once had with Franck upon this matter, it followed directly upon an audience at Court, after young C£sar had presented his works to his august patron, that he was forced by paternal authority suddenly to leave the Conservatoire, as his father based fantastic hopes upon this dedication. Unfortunately, nothing to justify them came to pass, in spite of a sojourn of nearly two months in Belgium.

HOWEVER that might be, the first trio in FG marks a step in the history step history of music; for it really is the first composition which, following the principle indicated by Beethoven in Jiis last quartets, establishes frankly—one might almost say naively—the great cyclic form, which no other composer since the Ninth Symphony had either recognized or dared to use.

We have no further details concerning the stay in Belgium, except that Franck met Liszt there, an'd from this meeting was bom the fourth trio. It is probable, however, that his father reaped none of the benefits which he hoped to find there; for in 1844 we find the entire family established again in Paris, with no other resources than the lessons or concerts which were given by the two sons, Joseph and C£sar.

This was the opportune moment which the latter chose in which to marry,

Having been in love for some time with a young actress, the daughter of a celebrated tragedienne, Madame Desmousseaux, he made her his wife in spite of the protests of both his parents, who were scandalized to see a young woman of the theatre brought into the family.

Now there began for Franck that life of regular and unremitting toil which lasted without a break for fifty years, and which allowed him no diversion except (and that but seldom) a concert where one of his works was given.

It was the first performance of his Ruth, a Biblical pastoral in three parts, which took place on January 4, 1845, in the Salle of . the Conservatoire, that brought Franck a certain success, though without further result. Most of the professional critics saw in the work merely "banal imitation" of Le Desert, by FGicien David, which was then in the enjoyment of a vigourous, though ephemeral, success. A little later, it was the name of Richard Wagner that the musical scribes employed with which to crush every new work; and that habit is still in force today, when the same scribes are ready to exalt a priori every youthful production, whatever its worth, at the expense of the masterpieces of an earlier day—a curious reversal of procedure.

Continued on page 114)

(Continued from page 110)

However, one of the critics, in 1845, with better judgment than his fellows, wrote of Ruth as follows: "M. Franck is naive, exceedingly so; and this simplicity has, we believe, served him well in the composition of his Biblical oratorio." Twenty-five years later, September 24, 1871, there took place at the Cirque d'£t6, under the composer's own direction, a second performance of Ruth; and the same critic, perhaps without remembermg that he had already heard this oratono, waxed enthusiastic, and wrote a revelation. This score, which by its charm and melodic simplicity reminds one of Méhul's Joseph, but with a tenderer grace and a more modem style, may boldly be called a masterwork."

IN 1851 the future composer of Ilulda adventured for the first time into dramatic music with the Valet de Ferme, rather colourless score which, furthermore, was never performed. Also, after having been for several years organist of the little parish at Marais, Saint Jean Saint Franfols, Franck found the calm and quiet retreat which was to be a veritable cradle in which to foster the new spirit of his genius.

THE present basilica of Sainte Clotilde was nearing completion to replace the little church of Sainte Val&re; Cavaille-Coll, that master inventor died poor, had installed there an organ splendid sonority to which he who the Second Prize in 1841, then organist Sainte ValSre, naturally succeeded 1859.

It was in the twilight of that gallery Sainte Clotilde, which I cannot without emotion, that the greater part Franck's life was passed; it was there for thirty years, every Sunday, every fdte-day, every Friday morning, he fanned the flame of his genius in admirable improvisations, often higher in thought than many a piece of music chiseled finished art. It was there, undoubtedly, that he conceived his sublime Beatitudes,

And so for several years he meditated, living the tranquil existence of organist and teacher; and to the feverish production of his youthful years there succeeded a period of calm during which he wrote nothing but organ pieces and religious music. This calm was but the precursor of still a third change, a final one, to which the world of music is indebted for works of the greatest value.

In 1869 a friend of the family, Madame Colomb, offered Franck the text of oratorio following closely step by the Gospel text of the Sermon on Mount. He was at once fired with enthusiasm for the subject, which appealed strongly to his devout soul and to passionate and generous nature, and composed the first part immediately.

His work was interrupted by an event that left no Frenchman unstirred, Franck, though born in Belgium, French in heart and sympathy. I to the Franco-Prussian War of 1870.

THOUGH too old for active service, Franck enrolled, like every one else, in the Garde Nationale Sédentaire, and had to see his young pupils scattered by the evil wind of defeat, leaving their study of counterpoint, organ or piano to go forth and handle the guns in the brave, hastily improvised armies, with which for six months our country endeavored to oppose the victorious invaders.

Many of his disciples never were to see again their beloved master. Three of them, Henri Duparc, Arthur Coquard and the writer of these lines (who had never yet dared to show him any of his crude efforts), were shut up with C£sar Franck in besieged Paris. One evening, in an interval of standing guard at the outpost, Franck, brimming with enthusiasm, read to these young men an article in the Figaro, which extolled in a prose sufficiently poetic, the superb vigour with which Paris, though sore wounded, still resisted. "I wish to set that to music" he cried, after he finished reading. A few days later, he sang to us with fervour the result of his labors, thrilling with patriotic inspiration and ardor:

"Je Paris, la reine des cites," etc. Never to this day has the ode been printed; but it is, I believe, the first instance of a composer venturing to set a prose poem to music.

IN 1872 there came to Franck a curious and unexpected preferment—he was appointed professor of organ at the Conservatoire, no one knows how; and he, such a stranger to intrigue, understood it least of all. Old Benoist, having reached the age limit (he had taught organ since 1822), finally retired to a wellearned rest. How did it happen that a Minister of Fine Arts, by chance endowed with some vision, bethought himself of appointing to the position the organist of Sainte Clotilde who was by nature and inclination so little of a politician? It is a mystery which no one has ever solved!

But, however it befell, Franck entered upon his duties February 1, 1872, and from that very moment he was the object of animosity, whether conscious or not, from all his colleagues, who never came to regard as one of themselves an artist who placed his art above every other consideration, a musician who loved music with an ardent and noble passion.

That same year he wrote the first musical setting to La Redemption, an oratorio in two parts, composed to a rather mediocre text by Edouard Blau; and Colonne, then at the beginning of his career as orchestral conductor, directed the first performance at a sacred concert on Holy Thursday, 1873. That performance, owing to certain circumstances, was far from satisfactory; for M. Massenet, whose Marie-Magdelcine was to be given for the first time two days later by the same performers, monopolized most of the rehearsals allotted for the two concerts, and the good Franck, without bittemess or rancour, had to content himself (and being so far from exacting, he actually was content) with a half reading, and a perfunctory performance, which failed to produce any effect. Owing to lack of time for preparation, he was even obliged to omit the great symphonic piece which separates the two parts of the work, and which, as a matter of fact, he completely rewrote later,

A SIDE from Les Eolides, a symphonic poem for orchestra after the verses by Leconte de lisle, which was produced at a Concert Lamoureux in 1875 and was not in the least understood bv the public, Franck worked scarcely at all during the six years following the composition of La Redemption except upon his oratorio, Les Beatitudes, which he did not finish until 1879, and which therefore occupied him during ten years of his life.

Convinced that he had produced a beautiful work, the master, whose innocence of mind made him an easy prey to delusions, imagined that the Govemment of his adopted country could not fail to be interested in the production of so noble a work, and that if the Minister could but hear his new score, he would undoubtedly appreciate and favour a performance.

Franck therefore arranged for a private audition of Les Beatitudes at his modest apartment in the Boulevard Saint Michel, after having carefully ascertained what day would be convenient for the Minister of Fine Arts, and after having personally sought out and invited the critics on the leading papers, the Director of the Conservatoire and the Director of the Opéra.

(Continued on page 116)

Continued from page 114)

The solo parts were confided to voice pupils from the Conservatoire; and the chorus, consisting of about twenty, was made up of Franck's private pupils together with some from his organ classes.

Franck was filled with delight at the prospect of this little performance, and intended to play the piano part himself; but two days before the appointed time he sprained his wrist while closing a carriage door, and it was to me that he entrusted the task of performing the piano reduction of the orchestral score to his selected guests, upon whose approval he was depending so absolutely.

ALL was in readiness, none of the participants was missing, and we only awaited the arrival of the guests, when a message was brought from the Minister, expressing much regret that he was unable to lie present. The Directors both of the Conservatoire and of the Op6ra had already sent their excuses. As for the leading critics, they were kept away by a duty much more pressing than to give a hearing to an oratorio by a man of genius—they had to attend the opening performance of an operetta in a women's theater! Some of them did indeed put in an appearance, only to leave almost immediately, and there were only two of the listeners who remained until the end: Edouard Lalo and Victorien Jonci£res did yield to Franck that mark of respect. But from this audition, which he had promised himself was to bring such good fortune, poor Franck turned away sad and somewhat disillusioned; not that he doubted the beauty of his score, but because every one, and even we his friends (who have said our mea culpa), made no effort to conceal our opinion that a performance of the complete work was impossible. He had, however, made up his mind, though with some bitterness, to divide the oratorio into sections; and it was thus that he offered it to the Soci£te des Concerts du Conservatoire, which made him wait a long while before they admitted even one of the eight parts to its programmes.

Fourteen years later, Colonne, who wished to have his revenge for the strangling of La Redemption, performed with great care and a real desire for an artistic rendition, the oratorio of Les Beatitudes in its entirety. The effect was overwhelming, and from that moment the name of Franck was surrounded by a halo of glory, growing ever more refulgent; but the great master had already been dead three years.

Following the unfortunate private hearing which has been mentioned above, the Minister of Fine Arts, who was perhaps a little remorseful, endeavored to have Cfear Frar.ck appointed one of the instructors in composition at the Conservatoire in the position left vacant by the death of Reber; but it was the composer of Madame Turin pin, Ernest Guiraud, who was preferred to the composer of Les Beatitudes.

On the other hand, and as a sort of compensation, the Government conferred a distinction upon the master; he was raised, together with bootmakers, tailors and every sort of purveyor to official needs, to the high honor of an Officier d'Academie!! Some years later, in 1886, Franck did indeed receive the ribbon of a Chevalier de la Legion d'Honneur; but it would be a mistake to imagine that this distinction was conferred upon the composer whose many works have brought glory to French music—not at all; it was to the official who had completed more than ten years of routine service that the Cross was awarded, and the "Journal Officiel" merely makes the following statement: Franck (C6sar Auguste), professor of music. The French Government was decidedly maladroit in its dealings with our composer!

THE last four years of Franck's life witnessed the completion of four masterpieces which remain as beacon lights in the history of French composition: the Sonata for piano and violin, dedicated to Ysaye, the Symphony in D minor, the Quartet for strings, and the Suite of three chorales for organ, which was his last composition.

The symphony was performed by the Société des Concerts du Conservatoire in February, 1889, contrary to the wish of most of the players in that celebrated orchestra, and chiefly thanks to the amiable pertinacity of their conductor, Jules Garcin. The subscribers had no idea what it was all about, and professional musicians had but little more. One of them, a professor at the Conservatoire and an influential member of the Comit6 des Concerts, to whom I expressed my admiration for the work and for its performance, answered me scornfully, "That a symphony? But, my dear sir, one doesn't write for English horn in a symphony. Do you find it, for instance, in the symphonies of Haydn? No, of course not. So you see that this music of your friend Franck is not even a symphony!" At another door of the concert hall the composer of Faust and Mireille, surrounded by a bevy of admirers, especially of the gentler sex, declared pontifically that the symphony was "the assertion of incapacity carried almost to the point of dogma". Gounod should expiate these words in some musical purgatory; for, coming from a composer of his quality, they could not have been sincere.

PLAYED triumphantly all over the world by EugSne Ysaye, the violin sonata was to Franck a source of unalloyed joy; but he was greatly astonished by the success, then without precedent, of his string quartet at one of the concerts of the SociStl Nationale de Musique, although he was one of the founders of that society, and had been elected its president several years previously.

At the first performance of the quartet, the members of the Soci6t6 Nationale, whose education toward works in the new manner was already in progress, were seized with an enthusiasm as sincere as it was contagious. In the Salle Pleyel, ringing with applause, all those present remained on their feet, shouting and calling for the composer who, not being able to imagine such a success for a string quartet, insisted upon believing that this demonstration was intended for the players. However, when he appeared, shy, smiling, amazed, upon the platform (in those days a composer was very rarely called out), he could not doubt for a moment that the delirium caused by his quartet was intended for himself; and the following day, proud of his first success (at the age of sixty-eight!), he said to us naively, "Well, you see the public begins to understand me."

These agreeable impressions were to be his but a short time to enjoy, for during the summer of 1890, while taking one of his early walks about Paris and perhaps preoccupied with some musical idea, he failed to avoid collision with an omnibus and the pole struck him in the side. Disregarding his physical pain, he continued to lead his ordinary life of fatiguing work; but soon a serious pleurisy developedhe had to take to his bed and finally succumbed to the disease November 8, 1890.

ONLY a short time before his death he wished to drag himself again to his organ at Sainte Clotilde in order to indicate the registration of his three organ chorales which, like Bach one hundred and thirty years before, he left as a splendid legacy to the world of music.

(Continued on page 118)

Continued from page 116)

His funeral ceremony was simple, as his life had been. By special authorization the services took place not in his own parish of Saint Jacques but in the basilica of Sainte Clotilde, where for thirty years he had canted almost daily the glory of God. Canon Gardey, rector of Sainte Clotilde, who had administered the last rites of the church to Franck on his deathbed, delivered from the pulpit an eloquent oration; then, without pomp or ceremony, the cortdge proceeded to the cemetery of Montrouge, where the remains were interred in a remote corner.

There was no official delegation either from the Ministry of Fine Arts or from its personnel to accompany Franck's body to its last resting-place. Even the Conservatoire dc Musique, in whose corps of instructors he was included; the Conservatoire, whose directors ordinarily let slip no opportunity to present themselves at the customary public ceremonies around the tomb of some empirical singing-teacher or some obscure professor of solfeggio;—even the Conservatoire neglected to send any representative to the obsequies of its truly great organ teacher, whose noble ideals of his art had always seemed dangerous to the academic quiet of that institution.

The many pupils of the master, his friends, those musicians who had become attached to him through his unlimited geniality—these alone formed a crown of love and admiration about his grave.

CÉSAR FRANCK in dying had bequeathed to the country of his adoption a symphonic school full of life and creative vigor, such as France up to that time had never produced.

And it was with most accurate prevision that Emmanuel Chabricr (who survived him so brief a time) concluded in the following words the very affecting eulogy which he delivered at the tomb on behalf of the Société Nationale de Musique: "Farewell, O Master, and thanks—your task was well done. It is one of the greatest geniuses of the century' whom we salute in you: it is also the incomparable teacher whose marvelous precepts have produced an entire generation of sturdy musicians, thoughtful and consecrated, armed at all points for the righteous battle, however long it may lie waged. And to the honorable and upright man, so kindly and unselfish, who never spoke aught but good, and who always gave wise counsel—to him also, farewell."

Fourteen years after this intimate and affectionate funeral ceremony, the same pupils, the same friends, the same musicians—somewhat decimated, alas! by death—came together again in the square which faces the basilica of Sainte Clotilde, to dedicate the monument erected by subscription to the memory of the beloved composer; but this time an enthusiastic crowd surrounded them, this time official dignitaries occupied prominent places, and both the Minister of Fine Arts and the Director of the Conservatoire delivered eloquent orations. What had happened during these fourteen years? Very quietly and almost unheeded the name of C6sar Franck, but lately' revered by a few' disciples, had become renowmed. Therefore the Fine Arts and the Conservatoire, which during his lifetime had ignored the modest organ professor, hastened to claim him as their own.

AND several young composers who had feared lest they might jeopardize themselves by going to him for instruction discovered as by enchantment that they had been numbered among his pupils.

The Institut de France could not, however, be represented at the dedication of this monument; for whereas it had welcomed to its bosom such conspicuous mediocrities as the composer of Les Noces dc Jeannette or the writer of Ie Voyage en Chine, to mention only those who are no longer living, it had never opened its doors to one of the greatest musicians who had ever brought honor to our France.

And this just reversal of public opinion is the more securely established as it is not founded upon sterile intrigue or the effort to reach an ephemeral success, but rests solely on the sincerity and the immortal beauty of works that remain ?„s an example to all who would make themselves worthy' to bear the noble name of composer.

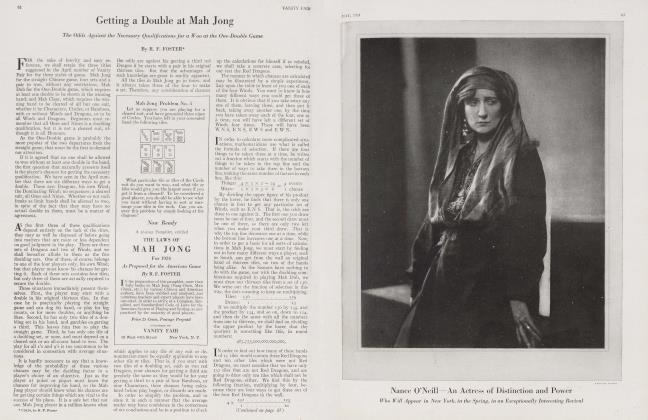

IN physical appearance, Franck was short of stature, he had a high forehead, an animated and open expression, though his eyes were almost buried under the sheltering brows; the nose wras rather large, and the chin retreated under a wide and extraordinarily expressive mouth. His face was round, and this was accentuated by luxuriant whiskers, which were turning gray.

Such was the figure which we loved and honored for twenty' years, and which, except for the whitening of the hair, changed scarcely at all till his death.

Certainly there was nothing in his appearance which seemed to indicate the artist, or which conformed to the type created by' romantic legends coupled with the traditions of Montmartre. Who, indeed, encountering in the street that individual always in haste, trotting rather than walking, with a preoccupied expression and frequent grimaces, clothed in a coat too large and in trousers too short, could have imagined the transformation which took place when, at the piano, he explained or commented upon some piece of beautiful music; or still more when, with one hand to his forehead and the other arrested in the direction of the stops, he sat at the organ making ready for one of his charming improvisations? Then did music seem to envelop him entirely as with an aureole; then only was one struck by the purposeful firmness of the mouth and chin, by the almost superhuman keenness of the eyes, in whose light gleamed inspiration; then only' one noticed the almost perfect resemblance of his fine and broad brow to that of the composer of the Ninth Symphony; and one could scarcely' avoid feeling a sort of superstitious awe in the presence of the genius which illumined the countenance, so surpassingly' fine and noble, of the greatest musician produced by France during the nineteenth century.

THE quality which predominated above all others in Franck's nature was his capacity for work. Winter and summer he arose at about half-past five every morning. He generally devoted the first two hours of the day to composition, which he called working for himself. At about half-past seven, after a frugal breakfast, he started out to give lessons in every corner of the capital; for, almost up to the end of his life, this great man had to spend the greater part of his time in giving piano lessons to amateurs in the music departments of colleges and boarding-schools. Thus all day long he traveled about, on foot or by' omnibus, from Auteui] to the Isle Saint Louis, from Yaugiraud to the Faubourg Poissoniere; and he did not usually return to his quiet apartment in the Boulev ard Saint Michel until it was time for the evening meal. Although fatigued by his day of toil, he still could find a few moments for copying or orchestrating his scores, when he did not devote the evening to receiving his pupils in organ or composition and lavishing upon them valuable and disinterested counsel. But it was during his two hours of work in the early morning, coupled with the few weeks of vacation which his position at the Conservatoire allowed him. that his greatest and most beautiful compositions were created, planned and written.

(Continued on page 122)

Continued from page 118)

If Franck was a stubborn worker, it was not that, as a result of his labours, he sought in any way for glory, profit or an immediate success. On the contrary, his only desire was to express his thoughts and emotions as ably as he might, and to give his best to the art that he loved; for he was, above everything else, modest.

Never had he known that feverish desire which gnaws at the very existence of so many artists; I mean the lust for honours and advancement. It never occurred to him, for example, to aspire to the chair of a Member of the Igstitut; not at all because, like Degas and Puvis de Chavannes, he disdained the title, but because he innocently thought he had not accomplished enough to deserve it!

This modesty did not, however, exclude that quality of self-confidence which is so important to the creative artist when it rests upon sober judgment and is free of vanity. When, at the opening of the autumn session, the master, with his face illumined bv his generous smile, would say to us confidentially, "I have done good work during my vacation, I believe you will be pleased," we were sure that presently some masterpiece would be disclosed.

HIS joy was to find in his full life some hours of an evening when he might assemble his favourite pupils and play for them at the piano some newly completed composition, aiding himself in the vocal portions by a voice as grotesque and uneven as it was expressive and warm, He never hesitated to ask his pupils' opinion of his work and even to adopt the suggestions they ventured to make, if they seeemed to him well founded.

Unfailing industry, modesty and high artistic ideals—these were the salient points in Franck's character; but there was another quality which is rare enough, and perhaps rarest among artists, which he possessed in a supreme degree—the quality of goodness, forgiving and indulgent goodness.

It must not be inferred that the master was of a cool and placid temperament; on the contrary, his was a passionate nature, and all his works give evidence of this, Who among us does not remember his holy wrath against vulgar music, his impatient start when the bell at the altar forced him to end too abruptly an mterestingly developed ojjerloire, his torrential invectives when at the organ our awkward fingers strayed toward faulty combinations? But these passionate outbursts, of the meridional du nord generally had for their object some artistic principle, they were very seldom directed toward any person; and during the long years which I spent at his side I have never heard it said that he had in any way consciously given pain to any one. How could he ever have done so, since his soul was incapable of conceiving anything evil? Never would he believe in the base jealousies which his genius provoked among his confreres (and not among those of least reputation); for he passed through life with his eyes lifted to a high ideal, and was always unwilling to give credence to the inherent failings of human nature, to which, unfortunately, those of artistic aptitudes are far from being immune,

FRANCK drew his strength and goodness from his religion, for he was very devout; with him, as with all who are truly great, belief in his art was associated with faith in God, the source of all beauty, Some ill-informed critics endeavored to compare the Jesus, so divinely loving and compassionate, of Les Beatitudes to the sorrowful weakling depicted under that name by Ernest Renan—certainly these gentlemen have never understood the music of Franck, and most completely would they have been undeceived if, like some of us who were admitted to the gallery of Sainte Clotilde, they had been permitted to join in the act of devotion so simply performed by the master each Sunday when, at the Consecration, he interrupted his improvisation and, leaving the organ-bench, went to the corner of the gallery to kneel in fervent adoration before God present on the altar,

Franck was religious, as were Palestrina, Bach and Beethoven having fait in a future life, he never debased his gift to seek therefrom a vain renown, he possessed the simple honesty of true genius, And while the ephemeral vogue of many composers who laboured merely to acquire fame or to win fortune has commenced surely to retreat into a shadow whence it will never return, the seraphic figure of him who wrote IJIS Beatitudes and who composed purely for music s sake, ascends ever higher in the light to which, without compromise or cessation, he directed his entire life.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now