Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowFrom Riches to Rags—and Return

The Remarkable "Success" Story of Wallace T. Crosby, President of the Lead Pencil Trust

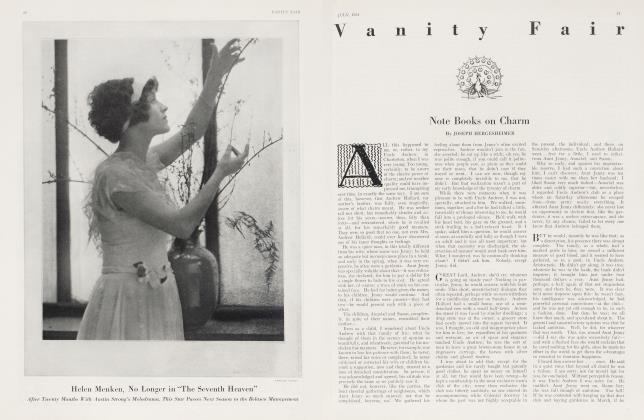

Mr. CROSBY HIMSELF

EDITORS' NOTE. As a rule, Vanity Fair does not publish articles of this type, preferring to leave the field of Big Business, commercial success, how to get your salary raised, how to sell goods, etc., to the "American Magazine" and other publications which have made it their specialty. Mr. Crosby's story, however, is so unusual, and presents so vividly the attainment of business eminence, not by special ability, but by close, rigid adherence to a formula that we deem it our duty to give this remarkable recital the widest publicity. It is a thrilling human document, in which we find, not only a lesson, but a message of radiant cheer for all who, "at the turn of life's road", as the author gracefully terms the age of fifty, find themselves discouraged and dismayed. To all such, we heartily recommend a close perusal of Mr. Crosby's story; yes, as well as to others who, though they may have been more fortunate in their business affairs, never know when they may be called upon to help some struggler along the way. For, after all, it is in helping others that we may achieve the greatest happiness.

FIVE years ago, on my fiftieth birthday, I was a failure. When I say this, I do not mean that I had failed to attain a competence, or that I was struggling along in a minor position, living beyond my income and worrying myself sick when the bills came in. I had passed through, and beyond, all that. I had no more bills, because I had no more credit.

Frankly, I was a member of the down-and-out class. So destitute was my condition that I was reduced to selling lead pencils from a tray, which I carried every morning to a corner little frequented by the police, for I had never been able to get sufficiently far ahead to buy a peddler's license. In my illicit relation to this humble trade, I was a bootlegger.

How I came to fall to this low estate has a direct relation to my story. Ten years before, at what I then considered the peak of my career, I had been elected Second Vice President of the Atlantic Salt Fish Food Company, with a main office in Boston and branches in Noank, Connecticut, and Bucksport, Maine. The object of this company was the sale to the country at large of every fish product to be found on the Atlantic seaboard. The President of the Company was James S. Scaffold, one of the most brilliant and compelling minds that I have ever come in contact with. It was under the expert instruction of the perspicacious Mr. Scaffold that I entered business.

In appearance. Scaffold was not unlike James G. Blaine, with the same eloquence and fire in his make-up. It was through him that I became interested in the company, and eventually became an officer of it. A legacy of ten thousand dollars, my share of my father's estate, represented my entire working capital. How Scaffold heard of this, I cannot say, unless it was through the perusal of the legal notice of such bequests which was published, according to law, in the Boston Transcript and other papers. I know he always kept careful track of such matters. Many a time later, I recall, he laid down his paper and said to some one in the office, "I see that young So-and-so has just come into a piece of money. Wouldn't he be a good man for our company?"

My progress in the company was slow. I was first engaged as a fish checker and counter on the docks of the Noank plant. My salary was fourteen dollars a week, and my job was to tabulate the hauls as they were dumped out of the nets in the packing house. It was exhausting and exacting work, for I knew nothing about fish; yet I was supposed to keep accurate count of the numbers of boney-fish, black-and blue-fish, cunners, flounders, lobsters, and so on, that made up the writhing, indiscriminate masses of our product. I could tell a lobster from a fish, but that was as far as I could go.

During the first six months of my apprenticeship, I used a hand-book on ichthyology, How to Know Our Finny Friends. It was illustrated with coloured plates. Book in hand, I rushed from one tub to another—there were twenty of them scattered about the dock—a method which naturally slowed up my work. Many a night, I stayed in the shed far into the dawn, going over the tubs to check any possible mistakes and to verify my tally. Cold, freezing work it was, for the fish were packed in ice; and I often turned in at my boarding house with hands frozen, reeking of mackerel or cod, blue and discouraged, but encouraged by the hope held out by Mr. Scaffold that, if I worked patiently through the humble stages of the business, he might some day find a place for me higher up.

A Magnificent Opportunity

I SHALL never forget the day he sent for me to meet him in the Boston office. My chance had come. The business was going and needed more capital for larger offices and increased overhead. The profits were enormous; but, he assured me, he and his partners had put everything back into the pot, taking out only a modest living. If I chose to invest my capital, it would help the company and assure me a life of luxury in my old age, allowing only reasonable time for development. It was too good to be missed, so I signed up at once.

The next few years were the years of development to which Scaffold had referred. From time to time, we needed new capital; and I have never seen a man so capable in finding it as was our President. He seemed to know by instinct where money was and how to call it out of the pockets of even the most tight-fisted New Englander. I remarked on this once, and he said, with the modesty that always characterized him, "It's a gift, my boy, a gift." There was no doubt upon this point.

In the spring of 1919, we had just expanded again, due to the entry into our company of Ogden Furlong, whose father had left him a large fortune. Furlong at once became one of our Vice Presidents, of which we had fourteen at the time; and the activity of the office increased amazingly.

A month later, Scaffold called us all into his private office. His face was tense with excitement. "Boys," he said—he always spoke of us as "his boys"—"boys, the Atlantic Salt Fish Food Company is due for a tremendous expansion. We have exhausted the Eastern seaboard. What is the answer? We must sell the middle west. We must teach the man in Montana that he can have fish-balls for Sunday breakfast. And who can do this as well as my boys? No one. I have mapped out a colossal selling campaign. I have divided the country up among you. Jones, you take the south-western states; Crosby, the south-central; Furlong, the north-central—here are your routes. Here are the literature and order blanks. Miss Gadgett will give you your traveling expenses. We start tomorrow. Let's go."

The Disillusionment

WHEN I left the office next day, it was deserted, except for Miss Gadgett—a lovely, blonde creature, by the way—and the President. They bade me good-bye cheerily. "We shall miss you," they said, "but never mind. It is all for the cause. Carry on."

I was doomed to a period of distressing disillusionment. My allotted section of the country was in no way interested in salt-water fish. Many of the inhabitants said they had gone west to avoid them. In vain, I described the beauty of our blue-, black-, and white-fish, our green mackerel and red snappers. In vain, I spread out the colour-cards which Scaffold had printed, showing them in their pristine beauty. I traveled, in all, over four thousand miles, and did not sell a fish. Whenever I was in a dining-car, which was every day, I ordered fish in a loud voice, and quarreled with the waiter when he tried to bring me some flabby, local product.

Little did I realize how this dining-car life was to affect my future. It has always been my habit, after writing out my order in a dining-car, to thrust the pencil supplied by the road in my pocket. Why I do tins, I do not know; but the habit persists to this day. As I wandered vainly from Cedar Rapids to Oak Bluffs, from Oak Bluffs to Omaha, peddling my fish, I amassed quite a collection of pencils. I must have had over a hundred of them. Then came the tragic end. My traveling fund ran out. I wired for more. There was no answer. I wired again, collect. The message was returned with the notation, "Office closed". With a sinking heart, I pawned my watch and a set of razors which I valued highly. Thus I scraped up enough money for my fare to Boston. I shall draw the merciful curtain of silence upon the mental tortures I suffered on the way.

Nothing has ever been heard of Scaffold or of Miss Gadgett. Let that pass. I was destitute, crushed, broken. My faith in man was gone. I had not the courage even to apply for a job. And then, I thought of my lead pencils. It was all I could do. I rigged up a tray from the top of an old orange crate and roamed hopelessly through the streets of Boston, saying, in a weak, unconvincing voice, "Pencils, pencils."

(Continued on page 86)

(Continued from page 39)

Occasionally, some kind-hearted Bostonian would pause, look at my tray, and say, "Why, so they are!" Once, a man who wore a railway conductor's cap scrutinized me sharply, and I sank into a side-street. But I never sold any pencils. My heart was not in my work. Daily I grew thinner and thinner, until, one afternoon, I fainted in front of some sort of public institution. When I came to, I found myself in a chair at the back of a large hall. It proved to be the auditorium of a branch Y. M. C. A. A professional fund-raiser was giving his final instructions to a group of keen-faced men who were about to start their yearly drive for funds. In spite of my weakness and apathy, his words bored into my brain; and, as I listened a strange, wild hope sprang in my breast.

The Great Awakening

"MEN," said the forceful, redhaired speaker, "I have told you before, and I tell you again, there arc just three things to keep in mind in selling the *Y'; three things which, if you've got 'em, make it possible to sell anything on this green footstool, and without which you couldn't sell eyes to a blind man. Let me go over these three things once more, and then I'm through.

"First, you must believe in a thing. You believe in the 'Y', don't you? Because if you don't, if there is a single man in this room who doesn't believe, heart and soul, that he's got a good product to sell, something the city of Boston needs and must have, let him stand up and declare himself. We don't want him. Let him do something else.

"Next, you must know what you've got to sell. You must know your subject, inside-out, all over. When a man asks you how much our expenses are and what he is expected to give, you must have your answer ready. You must know the membership of the branch you are working for, the courses it offers, the moral value of it. You must have the whole story pat. It is all in the information folders you already have.

"Third, stick to it! Don't go after this thing in a half-hearted way. Don't call up your man on the 'phone and ask him if he is interested, and if lie says 'no', say 'all right'. See your man. Go at him; hard, but not brutally. Don't say, 'We expect you to subscribe so much'; that gets any man's goat. Say 'We hope—', or 'Mr. So-and-so, wouldn't you like to join the Hundred Dollar Club?' Don't let him talk. You do the talking. When you see that he is about to interrupt and that he is not quite sold on the proposition, raise your hand and say, 'Just one minute! I'm not through yet!'—then go on with your talk. Have your blank ready; and when you see him begin to hesitate, have the old fountain pen right in your hand, slip it into his fingers, and the trick is done. Go to it!"

The meeting broke up as I sat there in a whirl. I saw it all so clearly now: why I had failed so dismally, why I had made such a mess of my life. I had never believed in what I was selling. I hadn't believed in fish; I hadn't even believed in lead pencils; and now it was too late.

But was it?

The speaker had said something about having to know your subject thoroughly to believe in it. I could never go back to fish, but I still had my pencils. What did I know about them? Nothing. With a strangled cry, I rose from my seat and tottered toward the public library.

One week later, I stood on the corner of Copley Square, my tray about my neck, my eye seeking the first likely looking customer in sight. He approached, an elderly, austere gentleman, who surely knew how to write. I literally sprang at him, with such vigour that he paused in amazement.

"My dear sir," I said, "I feel sure you will be interested in these pencils. Many a man goes through life, never having known the perfect pencil, constantly disappointed in points that break off or wood that splits. Let me tell you something about these pencils, in which I have the most perfect confidence, because I know all about them. Wait!—I am not through yet!

"The finest graphite in America is mined in Ticonderoga, New York. That is what is in these pencils. After the graphite is mined, it is first reduced to an impalpable powder by grinding. Water is then added, and the product is run through mixers in a fluid state. Don't interrupt!

"The finest quality of clay is then added to the composition and thoroughly blended with it. A little lamp-black is sometimes used, to increase the blackness.The mass is then placed—one moment, please!— in a filter press and forced through successive plates, with die-holes of varying diameter.

"The cedar for these pencils is specially grown at Lebanon, Connecticut—yes, sir, these are the famous cedars of Lebanon. Now I had hoped that you would be interested in joining our Ten Pencil Club. How's that? You will? Sir, I thank you; and at the same time, I congratulate you. As far as pencils are concerned, you have reached perfection."

My Success

THE rest of my story is briefly told. I am now President of the Crosby Pencil Company, which is the only rival of the famous German and English concerns, and those I think of buying out. It was all accomplished by the methods which I first sensed on that memorable day when I fainted from fatigue and literally fell across the threshold of success. Needless to say, I am the most enthusiastic booster of the "Y" in my part of the country.

In closing, let me apologize for having dwelt at such great length on my early days. My only excuse for doing so is that it is always pleasant to talk about one's failures, after one has achieved success.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now