Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowWhere Adam Lives in America

Charleston, South Carolina, Where The Great Period Still Gloriously Survives

WALLACE IRWIN

You got honey?

Yaas ma'am, Ah got honey.

Wha you got dat honey?

Ah got it en de comb.

You got strain honey?

Yaas ma'am, Ah got strain honey.

Wha you got dat nice strain honey?

Ah got it en dc jah.

You got nice patched peanuts?

Yaas ma'am, Ah got nice patched peanuts. Wha you got dose nice patched peanuts? Ah got 'em in de bag.

THE old honey man, half blind, totally deaf, goes flat-footing down Tradd Street, his face withered and black like a prune, yet vital with a lyric rapture. For the old honey man has made a song which poetizes trade and offers possibilities for the lazy music of his voice.

A young mulatto woman, her skin a golden brown, her eyes teasing, looks up from the astonishingly large brass knocker she has been polishing with the distracted, leisurely air of an African, unbossed and working by the hour; the doorway itself is eloquent of the Brothers Adam who conceived its like; double pilasters, slender and delicate, with a gracefully dentated, hooded top, carved mouldings and a little stuccoed rose-garland under the sheltering peak. The mulatto woman stands, arms akimbo, her polishing rag loosely dangling, and calls after the shuffling peddler. "Hi!" she shouts, smiling broadly. But the honey man shuffles on, oblivious.

Not only is he deaf, but the song has charmed away his senses.

"Yaas, ma'am, Ah got honey.

Wha you got dat honey?

Ah got it en de comb. . . ."

In my mind that scene symbolizes

Charleston today, yesterday, tomorrow and forever. A gracious doorway, its original contours softened by generations of overpainting, and a fragment of the old order faring by, charmingly loquacious, weaving a melody and making no concessions to modern methods of barter and trade.

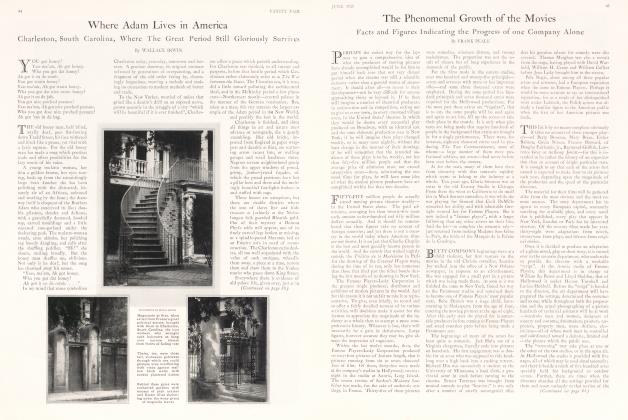

To the New Yorker, wearied of noises that grind like a dentist's drill on an exposed nerve, grown neurotic in the struggle of a city "which will be beautiful if it is ever finished", Charleston offers a peace which passeth understanding. For Charleston was finished, to all intents and purposes, before that hostile period which Carolinians rather elaborately refer to as The War between the States. The Victorian era, it is true, did a little toward polluting the architectural ideal, and in the McKinley period a few plutocrats—Northerners mostly—erected palaces in the manner of the German renaissance. But, taken as a mass, this city remains the largest example of the Adam period in the New World, and possibly the best in the world.

Charleston is finished, and since all things in art and nature must advance or retrograde, she is gently crumbling. Her old bricks, imported from England in paper wrappers and durable as flint, are scattering across vacant lots, or walling garages and retail hardware stores. Negroes scream neighborhood gossip from the upper windows of proud, grimy, jimber-jawed fagades, of which the proud porticoes have lost a pillar here and there and the meltingly beautiful fan-lights broken in and stuffed with rags.

These houses are exceptions, but there are sizable districts where the sons of slaves live and hide treasure as jealously as the Nicbelungen folk guarded Rhenish gold. Out of their mystery a Duncan Phyfe table will appear, one of its finely curved legs broken or missing, or a spindle-posted Sheraton bed or an Empire sofa in need of reconstruction. The Charleston curio dealers, all too well acquainted with the value of such antiques, wheedle them away, a piece at a time, restore them and show them to the Yankee tourist who passes down King Street.

Everywhere there is evidence of old palace life, given over, just as in England today it is being given over, because a feudal aristocracy has perished here and is perishing there. When the Carolinian baron, .descendant of the noble Lords Proprietor of Carolina, rode for a day and a night over his linked plantations of indigo, rice and cotton; when he could count his slaves by regiments and Charleston harbor was lively with fleets of merchant ships, taking on exotic cargoes, then he could build in the grand manner and in the best taste of his time.

(Continued on page 88)

(Continued from page 44)

I have been told that the Adam decorations (whether of Robert or James, those marvelous workmen and rulers of taste) came first to Charleston by way of the Barbadoes when the island planters sought the richer fields of Carolina. But this is not entirely an accurate statement. Or it is disputable, since Charlestonians are most beguiling when they disagree about their own town. It is safe to say that the Barbadoes men left the twodecked, plain verandahs, remindful of the Carrabees and the Cape Settlements and all tropic places where the white malt waves a palm leaf fan. But it is more logical to believe that the Adam type came legitimately from England. The artisans who in South Carolina devised the doors and mantels and graceful porches were often petty criminals, exiled to America to serve out their indentures; or they were honest freemen, imported for their skill; yet others were black slaves, trained to follow out the delicate patterns and to exercise a decorative taste which sometimes shows strongly in the African nature.

Huguenots at first, then exiles from France's great political sto-rms, brought with them the iron workers who wrought such balconies as hang over narrow streets from fronts of fading rose; theirs too were those tall arabesque gateways through which I have glimpsed so many urns, overflowing with vines against mellow brick walls with sunken plastered niches. How often have I peeked enviously in on masses of bravely pink azaleas and Easter lilies under the waxy green of magnolia leaves, and wondered that so much of romance has grown reticent in its cloistered obscurity.

Charleston, north of old St. Michael's defiantly Georgian belfry, is now given over to the industrialism of the white and the languor of the black. The overlords of Carolina once dwelt there; when Sherman turned war into hell and burned a swath through the architectural heart of America he centered his wrath on the great plantation mansions and was kinder with the town. This has never been satisfactorily explained to me, an unlettered Yankee. But the stately dwellings of the proprietors who had fattened on rice and dyed their togas in native indigo were left to the slow work of moth and mildew.

A Charlestonian courteously volunteered to show me through one of these handsome ruins; his family had dwelt there for generations and in his boyhood the grounds had been shaded by yellow locusts; vermilion gardenias had grown along the wrought iron fence, and the giant wisteria—which in Carolina will turn a forty foot tree to a violet miracle —had flaunted above the roof of the great square pillared house. Everything is bare now. When the place was turned into a school the trees were cut, the grounds trampled flat and a monstrous Victorian addition built on.

A colored caretaker, down the alley, was supposed to have the key, but upon application he scratched his wool and reckoned he "done loss it." Finally we entered by a back-door, secured by a rusty nail. For years, perhaps, no human beings had roused the dusty echoes in those littered halls. We clattered over the bare boards of a deserted classroom in the Victorian wing and came at last to a graceful arch through which we could look down—for we were on the second storey—along a spindled staircase that wound in a complex series of beauty curves to the wide foyer below. Decorations had been ripped from the walls and replaced by blackboards, still chalked with last generation's arithmetic lessons. The doorways were worked in high relief with flower-laden urns and slim-waisted dryads. Adam mantels in black, white and yellow marble stood broken and dismembered in every room; the wooden mantels were still intact and smiled, as gay and as elegant as of old.

The library, the panelled wainscoting of which was bordered with a deeply carved chain design, had doorcaps three feet deep, intended as shelves, probably, for heavy books and the classic busts of the period. Here a pillar had been ruthlessly torn away from the marble mantel. Into the long, distinguished dining room, light seeped vaguely through closed shutters and the hall's grimy fan-light. Adam's repressed ornamentation showed vaguely in the twilight. Here was distinction in the sere and yellow. . . . Thackeray, they say, once dined in this room. . . .

How much of this wreckage is blamable to natural decay, how much to the vandalism of school children and how much to the rape of war would be difficult to say. General Dan Sickles' troops were quartered here during the Civil War, and that will account for some of it. Sickles' first act upon occupying the house was to roll up the Turkey carpets, stack up the Sheraton furniture, tear down the family portraits and offer them as loot to the domestic servants, dwelling in the rear. The slaves carried it away with them by foot, by wheelbarrow, by ox-cart, and when the Union troops had departed an old butler returned and showed his master where his treasures had been stored away in whitewashed cabins under the live oak trees.

This is one of the houses which may have returned for a while to its former grandeur after the Civil War. But wealth had dwindled with the failure of the rice, and most of the prosperous Charlestonians have moved into "town"—which is that section of the city situate South of Broad Street. Here the thoroughfares are as meandering and as narrow and as eyefilling as the interminable alleys of Canton.

(Continued on page 92)

(Continued from page 88)

They twist into surprising angles; they double on themselves, and at every angle, every double there's a picture of the old world in the new A bijou of a house, with spindling columns for doorposts and a charming slope of roof, stands with its shoulder at a sharp angle. A great brick pile with double steps leading to a raised double verandah, the pillars of which are like trees, looms behind an iron gateway with Roman swords wrought into its design. From a pink facade a balcony swings like a square birdcage of Spanish lace. . . .

This is Charleston, just a fragment of it, which its inhabitants have never clamored to make public. Its very reticence lends it magic.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now