Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowHamlet in Mufti

Critical Notes on What the Young Men Will Wear in Elsinore This Season

ALEXANDER WOOLLCOTT

WHEN they were rehearsing that fearful tragedy in Mr. Sheridan's Critic, it was Mr. Sneer, who, on discovering that the fair Tilburnia was to "enter stark mad in white satin", made so bold as to inquire acridly:

"Why in white satin'"

"Oh Lord, sir," quoth Mr. Puff a little shocked, "when a heroine goes mad, she always goes into white satin. It's the rule."

At such quaint ways as contented our naive forefathers in the theatre, we have all smiled tolerantly from time to time. For instance, in that candle-lit performance of Hamlet, which the immortal Tom Jones and his man Partridge witnessed from the gallery of Drury Lane, the Melancholy Dane (whose terror of the Ghost was so infectious that poor Partridge had the vapours for many a night afterwards) was stylishly turned out in just such satin knickers, lacy cuffs, buckled shoon and snowy periwig as would have graced any beau of George IPs court dawdling that night in the Royal Box.

For, it was the custom in Mr. Garrick's day to garb all the Shakespearean characters in the mode of the moment. Mrs. Bellamy, whether she played Juliet or Jeanne d'Arc, did so in a hoop skirt so overwhelming that a page was needed to make it behave during her scenes of greatest emotion. And any scene which involved two emotional actresses at once created on the Drury Lane stage a nice traffic problem. On great occasions, Mr. Garrick would so far stretch himself as to costume a Greek hero of the Golden Age in something faintly resembling the every day working suit of a Venetian gondolier. But his Thane of Cawdor would go quaking about the bloody halls of Dunsinane in snug white knee breeches handsomely topped off with just such scarlet regimentals as used to grate on the twenty lovesick maidens in Patience.

NOW it so happens that our statute books contain no such beneficent clause as the edict of that fine, moderate, Chinese emperor who, some 2,000 years ago, decreed that all those making use of antiquity to belittle modern times should be put to death, together with their relations. T herefore, when overwearied by those sclerotic reviewers who ever lament the decline of the stage, I have, from time to time, derived no little solace from thinking of Mr. Garrick's day and laughing immoderately at the picture of his caldron scene in Macbeth. I herein the three weird sisters neatly got up in plaited caps, red stomachers and black lace mittens, must have seemed even weirder than the Bard had dared to hope.

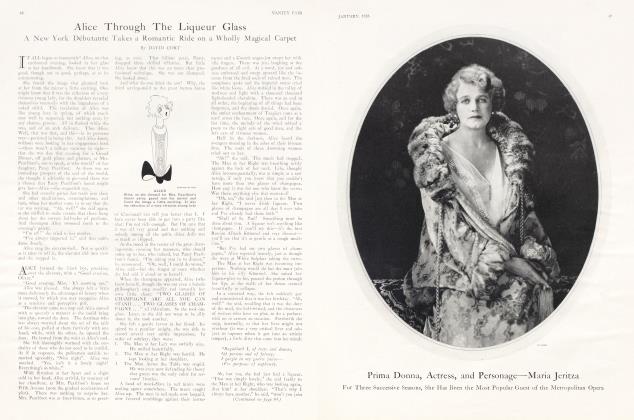

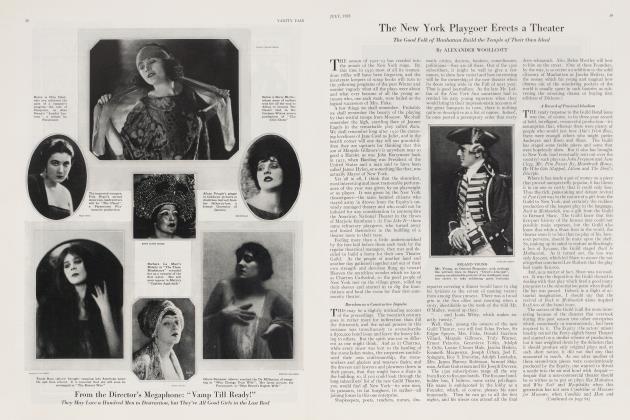

Yet not long ago, I attended a performance of Hamlet produced on the Garrick principle, a performance so living and good that it required a positive wrench of% a scrupulous critical attention to keep in mind that the Melancholy Dane, standing there with poor '⅛ orick's skull in his hands, was so far departing from recent custom as to be wearing a neat walking-suit of snuff-colored tweeds, a soft, slouchv overcoat, tan boots, a slim malacca stick and a squashy steamer-cap pulled down over his noble brow.

It was a production of Hamlet in which strains of muted jazz floated down across the palace grounds when the King kept wassail all in the great hall the night the old ghost walked. It was a Hamlet in which a Prince in a dinner coat watched The Mousetraf from his seat at the feet of an Ophelia all virginal in a pretty debutante's frock. It was a Hamlet wherein Polonius passed away modishly in a cutaway pierced with the revolver bullet which had torn its path through the arras to his eavesdropping heart. It was, in short, the Hamlet in Modern Dress, recently produced in New York by the. unquenchable Horace Liveright, that bold entref reneur who stands now with one foot in the publishing business and the other in the theatre.

The idea came from London, where the Hamlet in Phis Fours practically doubled the daily ration of letters to the Times from indignant old gentlemen but where the crowds flocked in to see it just the same. Prior to the experiment in New York, none other than our own Robert Mantell had tried it in such outlying art centers as St. Louis and Omaha, although that veteran of the classic repertory has, at the age of 7 1, been provided by relentless Nature with some externals which must have faintly confused the issue.

FOR Mr. Liveright proffered his Hamlet in Mufti only as an experiment. Much of the tart comment heard in the land before the fremiere was lucid only on the assumption that he was offering it as the way to produce Hamlet, whereas, of course, he was merely inquiring mildly if this were not a way to produce it. The reasons for costuming it in the manner made familiar to living playgoers by the Booth, Irving, Forbcs-Robertson, Barrymore and Hampden productions are so obvious that surely they need no expounding.

Of course, when Hamlet goes into mufti, something is lost. That might almost go without saying. But it was the whole argument of the recent revival that something wasalsogained. One saw the play as in a new light, as from a new angle, with old values lost, perhaps, but with new ones brought suddenly to light. I doubt if the habitual playgoer realized before how good were the roles of the King and Queen, how much to do with the play such minor figures as Roscncrantz and Guildcnstern had.

The experiment was somehow oddly akin to the new understanding a painter gets if he peers at his own canvas upside down, or throws himself out of joint in an effort to look at it under his own elbow. Stray Philistines, noting the fellow in this perplexing posture, will vow he is mad—or, at least, monstrously affected. But the dear, mad fellow may be discovering something about his masterpiece he did not know before.

I much suspect that the effect on the audience is indirect, that the chief effect is on the players themselves. Of course there be players whom I have heard others praise and praise highly, not to say profanely, who, even in the most acutely contemporary costume, seem ever reveling in lace at their wrists and a ready rapier on the hip. But even their betters grow a thought pompous the moment you thus thrust them into doublet and hose or festoon them in the flowing robes of the grand manner.

I ALWAYS remember the legend that John Barrymore, the best Hamlet of them all, never quite reached the pinnacle of performance witnessed by the favoured few who sneaked in to see the final dress rehearsal of the great tragedy on the eve of its first performance under the Hopkins management three years ago.

"And oddly enough," Ethel Barrymore used to say, "whereas the rest were in full regalia, he was not in costume at all, but just wore whatever old suit he happened to have on when someone told him there was going to be a rehearsal."

This was always told as the anecdote of a handicap bravely overcome. I am beginning to wonder if the ordinary pants did not help him out. And I'd wager a comely penny that Basil Sydney found the mouth-filling soliloquies far less abashing in a production wherein he was quite free to keep a cigarette sending up its incense before them.

IT IS surprising how little the text needed to be changed to keep lulled a too lively consciousness of its wild anachronism. I confess I myself was blissfully unaware of it almost all the time. Only once or twice did my sense of the incongruous mutiny. Once was in the moment when Hamlet, in his suits of woe (double-breasted) was chaffing that tedious gaffer, Polonius, and asking him if really now he did not think yonder cloud shaped rather like a camel.

"Methinks," I was in some panic that he would add "methinks it is like a Fatima."

Then, too, I was assailed with misgivings in that moment of agitation when the guiltv King conspires with his incestuous consort on the best means of wetting down the smouldering scandal left in the path of Polonius's murder. His notion is to summon round him at once all the best minds in monarchist circles, but my acute Shakespearean sense enabled me to pounce on him when he said:

"Come, Gertrude, we'll call up our wisest friends."

Unfortunately my shuddering at so flagrantly contemporary a line's being inserted in the text proved ill-advised. Shakespeare happens to have written it that way.

And even one who relishes such a bold experiment as Mr. Liveright made with the dramatic holy of holies ought, I suppose, to keep in mind that a tradition is not necessarily amiss. Perhaps something fundamental in the eternal playgoer is nourished by every custom of the theatre.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now