Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowIn a Turkish Bath

A Budapest Confectioner, Deceived by His Wife, Finds Solace in the Steam-Room

FERENC MOLNÁR

THE confectioner stood naked in front of me.

"Put something on," I said.

He looked around and threw a large white sheet over his shoulders. We could hardly hear each other's voices in the large echoing hall of the Turkish bath. Water was running and rushing everywhere. It was a refreshing and exhilarating sight. The sturdy bath attendants embraced, washed, douched and beat naked bodies amidst jets of water and white sheets.

Everywhere, I looked, sheets, naked shoulders, muscular arms, four or five ghostly figures wrapped in sheets wending their way towards the dressing compartments; my friend, a schoolmaster, completely naked except for his eye-glasses, was paddling about in the ice cold footbath, the while his finely-cut nose was pointed skyward, so that his long beard stuck straight out instead of hanging down.

"Come," said the confectioner, "this is no place to talk."

We went into what was known as the pack room. I wrapped myself up in a sheet and spread one on the bench.

"The scientific name," said the confectioner, "of my condition is traumatic psychoneurosis."

He bowed slightly while taking his scat, as if he were introducing himself.

"The pleasure is mine," I said, relieving the humour of the situation.

"Trauma," he explained, "is a wound which life inflicts. Psycho-pathology or something like that is the soul. Neurosis is a disorder of the nerves ..."

"Arc you from Pest?"

"No, I am from Buda. I own a confectionery store there. Well, I'll begin my story. My wife died, and I was left with five children. What can one do? I married again. I won't tell you what my wife's name was, as you arc sure to know of the family. They are Pest people, too. You know the town?"

"Yes."

"Well, then, perhaps I'd better just relate the case to you. You as an author will be interested in it. One afternoon at three o'clock I came home from a Cafe—"

"Ah, your wife is young?"

"Yes, but she was a widow. But what am I saying? She wasn't a widow, she was divorced from her husband, an officer of high rank; he is in Sarajevo now. I really don't know why l said she was a widow. She has fair hair, beautiful small eyes, not very large, but beautifully blue. She is not exactly stout, but one might say well-built. She is very neat and tidy and has a skin like milk and always wears a black velvet ribbon around her neck. People say she is a flirt, but I don't believe it. She is a bit conspicuous, that's true, but any well-dressed woman is conspicuous and talked about."

"Well you came home from the Cafe one afternoonr "

"Yes, I came home from the Cafe and saw a detective standing in the shop."

" 'What do you want?' I said.

" 'A summons,' he said.

" 'For me?'

" 'No, for your wife.'

" 'Show it to me.' It was really a summons.

" 'What is it about? '

" 'A subfoena to appear as a witness.'

" 'In what sort of a case.'

" 'An automobile accident.'

"'An automobile accident? Where?'

" 'I don't know, you'd better ask at the police station.'

" 'All right,' I said, as there was no sign of my wife at home, '1 shall run over to the police station right away.'

"You know I almost died from heart failure. I ran to the police station. I asked about the summons and they told me, 'First floor, door No. 14.'

" 'What about the summons that was sent to my wife:' I asked. The officer looked in the complaint-book and murmured, 'Oh yes, oh yes.' Then, after a moment, he said, 'At 8 p. m. Wednesday, May 27th, two motors collided on the Fehervar Turnpike. Your wife is wanted as a witness.'

" 'My wife a witness? Was she in one of the cars? ' 'Yes,' lie said, 'the chauffeur was there alone in one car, and your wife was in the other, with the owner, Dr. tdenry Vadasz, 84 Elizabeth Street, Budapest. He is also summoned as a witness.'

"Now, I knew everything.

"I thanked him and started to leave. 'Where are you going?' asked the officer. 'That's the bookcase. The door is there. To the right.' Did you ever hear of such a thing? I almost walked into the bookcase instead of through the door."

"Well, that is a good joke," I said to him, and laughed, with some constraint. A pause is necessary at such junctures as these—a slight breathing spell, or else the confectioner might become too excitcc. and not continue with his story. "That's very funny. Into the bookcase? Splendid .... Well, and then?"

"You can imagine . . . . I lingered in front of the police station as I felt unable to move. 'Ellis was the 'trauma', the consulting physician said—my not being able to move away. As to Vadasz, he was a lawyer with a good practice when his second wife was still living with her first husband. I was told, when I married her—a jeweller told me—that my second wife was divorced from her first husband on his account. But Vadasz wouldn't marry her because she had no money. I didn't believe it, at that time, although I knew that Vadasz was a frequent visitor at their house, and dined there every Sunday. I never saw him, but that is of no consequence. I walked home and waited and waited. At half past five my wife came home.

" 'Juci,' I said. 'Juci, the police have a summons out for you.'

" 'Oh, yes,' she said lightly, 'about the servant, you know the servant I dismissed.'

" 'Juci, it's not about a servant. It's about a motor accident. You have to be a witness,' and then I shouted, 'At eight o'clock at night, on the Fehervar Turnpike, you were in a car with Dr. Vadasz. Dr. Vadasz, Dr. Vadasz,' I said; that is, I screamed like one possessed, confusing everything—'you were sitting in his car. What were you doing at eight o'clock in the evening in a car on the main road? ' "

"Please," said I, interrupting the confectioner, "put the sheet around you, you haven't a stitch on."

"Pardon," he said, lifting up the sheet which had fallen off during his gesticulations, and held it, majestically, like actors in Greek tragedies, one shoulder bare, as lie started speaking again.

He went on.

"What do you think she said?—'Vadasz was here in the shop, he had something to do in Promontor. I complained of a headache and he said a little fresh air would do me good, and asked me to go along. So I did.'—Now, there's no harm in that."

Continued on page 114

Continued from page 60

"That's what the doctor said I suppose. I know the game—flirting in motor cars. 'Be careful we might be seen,—drive through the side streets,' I did the same once!"

"I know all about such things as embraces in motor cars. Once I kissed a woman all the way across the Suspension Bridge and the whole length of the tunnel without taking my lips away from her mouth.

"I said to her, 'All right, Helen, everything is all right. You have simply had a stroke of bad luck. Don't do it again, I believe you that this was quite an innocent affair, but be careful in future.' Then she started to cry and I left her alone."

A lump rose in his throat and he started clown the large hall without saying so much as adieu.

I sat for a moment and looked at him disappearing in the distance. Where I was sitting it was quite dark. The outer hall had a glass roof, and the sweet, hot, radiating July sun was pouring in through it. A smiling bath attendant, with a yellow apron took the confectioner in hand.

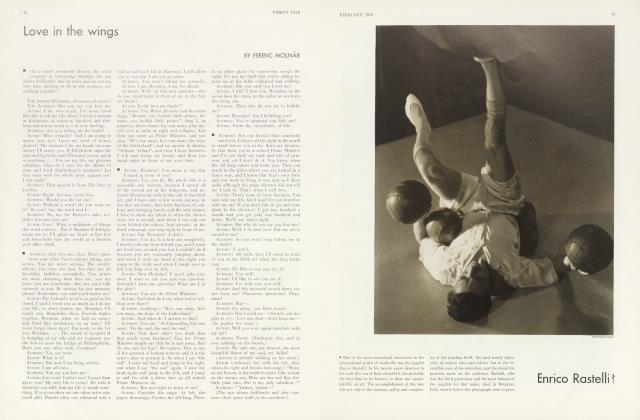

He stood quite naked, beneath the glass roof, revealing his lean body worn out with care. A wet sheet was thrown round him, and a shining brass crown was put on his head, through which cold water circulated. The sun shone on the brass crown and on the snow-white sheet which reached to the ground. His face was slightly distorted for he seemed to be struggling to hold back a flood of tears. His hands were beneath the sheet, and to wipe away his tears was impossible. He turned his head sideways that the tears might not run in his mouth. His eyes were wiped for him. The bath attendant with his powerful strong arms toughened by use, seemed to represent Life, which was now lifting this saddened man with his great grief. The most beautiful sight, which I can never forget, was, when the attendant kneeled down in front of him, embracing his legs, and the gaunt figure, clad in snow-white with the golden crown on his head looked down on him with a sorrowful, forgiving smile.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now