Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

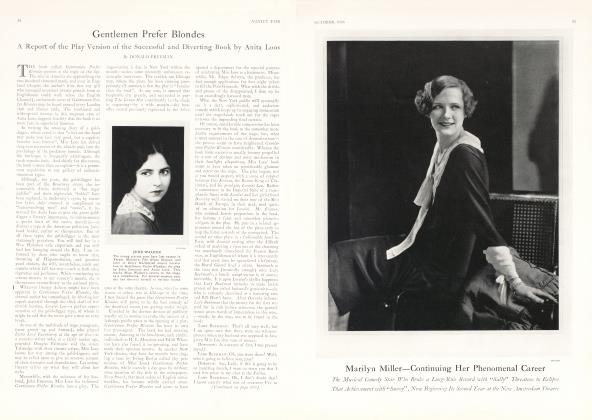

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowFridolin and Albertine

A New Story of Love and Adventure by the Celebrated Viennese Author

ARTHUR SCHNITZLER

TWENTY-FOUR brown slaves rowed the glittering galley which was bringing Prince Angid to the palace of the Caliph. The prince, in his purple robe, lay alone in the prow under the blue, star-spangled sky and his gaze. . . .

A little girl was reading aloud, then (almost suddenly) she closed her eyes. The parents looked at each other smilingly. Fridolin bent over her, kissed her blond hair and closed the book which lay on a table which was still covered with dishes. The child looked up guiltily.

"Nine o'clock," the father said. "Time to go to bed." And since Albertine also was bending over the child, the hands of the parents met on the beloved forehead. With a tender smile, no longer intended for the child alone, they exchanged glances. The governess entered, told the child to say good-night. Obediently she rose, raised her face to her father and mother, to be kissed, and, was unprotestingly led from the room. Fridolin and Albertine, alone under the glow of the hanging light, hastened to resume the conversation they had started before dinner about what happened at yesterday's Redoute.

IT was their first ball of the year, which they decided to go to and which occurred shortly before the end of Carnival time. Fridolin on entering the hall had been welcomed as an impatiently awaited friend 'by two red dominoes, although he could not be sure who they were, in spite of the fact that they recalled many incidents of his student and hospital days. After inviting him into their box with friendly assurances, they went away, saying they would soon return unmasked. But the red dominoes stayed away so long that Fridolin became impatient and went down to the Parterre, hoping to find them again. But, carefully as he looked, lie could find them nowhere; instead a woman took his arm casually: his wife had just escaped from the clutches of an unknown man, whose melancholy, blase manner (and foreign, apparently Polish accent) had at first fascinated her, but who, after a moment, offended, one might even say shocked, her by a suddenly inspired obscenity. Thus husband and wife came to sit in the buffet room like lovers, among other amorous couples rather happy to have avoided a part in a deceptive and banal puppet play. They • had oysters and chamfagne and talked lightly of the comedy of gallantry, of resistance, of seduction and of acquiescence as though they had just met. And after a quick drive through the white winter night, at home, they fell into each others arms in an ecstasy of fervour which for a long time they had not experienced. A gray dawn awakened them all too soon. The husband's profession called him to the sickbeds very early in the morning; Albertine's duties as housekeeper and mother did not permit her to rest much longer. Thus the hours went as if by a schedule of every-day duty and work. The past night, (the beginning as well as the end) had paled. Only now, their work done, the child gone to bed, and no fear of outside interruption, the shadows of the Redoute, the unknown and melancholy red dominoes became real once more. And these unimportant adventures were of a sudden magically and poignantly surrounded by the deceptive glamour of lost opportunities. Harmless, yet suspicious questions, and shrewd answers, shaded with double meaning were exchanged. Each was conscious that the other withheld the ultimate truth and thus both were inspired to a mild revenge. They exaggerated the attraction which their unknown Redoute partners had had for them, made fun of each other's jealousies and denied their own. But from the light banter about the unimportant adventures of the past night they fell into a serious discussion of those hidden, hardly conscious desires which possess the power to drag even the finest and purest souls into murky and dangerous whirlpools. They talked of secret realms for which they hardly felt a longing but into which the intangible winds of destiny might some day carry them only in dreams. For as completely as they belonged to each other in feeling and senses they knew that yesterday was not the first time that a breath of adventure, freedom and danger had touched them. Timorously torturing themselves with an almost prurient curiosity, they tried to draw out a confession from the other. Frightened, they moved closer together and probed inwardly for some fact or adventure (unimportant as it might be) which might in some way give expression to the inexpressible, and which, through open confession, might relieve the tension and free them both from the distrust which was gradually becoming unbearable. Albertine perhaps the more impatient, the more honest or the finer person of the two, found the courage to speak first. In a somewhat uncertain voice, she asked Fridolin if he remembered the young man who last summer at the Danish shore, sitting one evening at the next table in the company of two officers, had received a telegram in the midst of dinner, and then had taken sudden leave of his two friends.

"WHAT about him?" asked Fridolin sharply. "I noticed him that very morning," Albertine answered, "when he rushed up the steps of the hotel with his yellow handbag; he looked at me casually but when he had gone up a few steps he turned around so our glances were compelled to meet. He did not smile. On the contrary, it seemed to me that his face darkened. As for me, it scarcely made any difference, for I was moved as never before. The whole day I lay on the beach lost in dreams. If he had wanted me, I could not have resisted him. Of that much I felt I was certain. I thought I was ready for any sacrifice, prepared to abandon you, the child and my future, thought I had reached an absolute decision and yet—can you understand this? you were dearer to me than ever before. That very afternoon—you remember surely—it happened that we talked intimately about a thousand things—our future together—the child— as we had not done for a long time. At sundown we sat together on the balcony, you and I, when he passed without looking up—down below on the beach. And I was happy to see him, but I stroked your forehead and kissed your hair and in my love for you there was at the same time a mingling of real pity. That evening I was very beautiful (you said so yourself) and I wore a white rose in my belt. Perhaps it was not a coincidence that the stranger and his friends sat so near us, but I toyed with the thought of rising, going to his table and saying to him, 'Here I am, my long-awaited one, my beloved—take me.' At this moment, the telegram was brought. He read it, paled, whispered a few words to the younger officer and with a mystifying glance about him (which also included me) he left the room."

"And," Fridol in asked dryly when shestopped.

"Nothing more. I only know that I woke up the next morning with a certain indefinable fear. What I feared—whether he might have gone, or whether he might still be there—I don't know—I didn't even know then. But when he did not appear, even at high noon, I breathed more freely. Don't ask me any more Fridolin. I have told you the whole truth—And you, too, had an adventure on the beach—I know it."

FRIDOLIN rose, paced up and down the room and finally said, "You arc right." He stood at the window, his face hidden in the darkness. "In the morning," he began in a voice veiling a slightly inimical tone, "sometimes very early, before you were up, I used to wander along the beach beyond the village. And, no matter how early it was, the sun seemed always to be bright and strong on the sea. Out there on the beach there were small cottages, as you know, which, each a small world in itself, stood there, some with fencedin gardens, some only surrounded by woods— some with bath-houses, separated from the cottages by the road and a stretch of beach. I hardly ever met anyone at this early hour and there were never any bathers. One morning, however, I suddenly became conscious of a girl's presence. A moment before invisible, I saw her move carefully along the narrow walk of a bath-house, dug into the sand. Supporting herself by her arms, she was moving carefully along the side of the house against the wooden side-wall. She was very young, hardly fifteen. Her blond hair flowed down over her shoulders and over her tender breast.

SHE looked straight down into the water and slowly, with downcast eyes, glided along the wall toward the corner. In a moment she was directly before me. With her arms, she reached behind her as though to hang on more securely, looked up and saw me. A tremble ran through her body as if she were about to fall or to take flight. But since it was only possible for her to move very slowly along the narrow ledge, she decided to stop. She stood rigid, her face, at first, startled, then angry and finally bashful. All at once, however, she smiled—smiled wonderfully; there was a welcome, a wink even, in her eyes— and at the same time a mockery as she glanced furtively at the water at her feet which divided me from her. Then she stretched her young lithe body as if glad of her beauty and, as one could easily notice, proud and gently excited by the lustre of my look which she felt on her. Thus we stood—facing each other—for perhaps ten seconds, with half-opened lips and swimming eyes. Automatically I opened my arms to her and in her glance was love and joy. Of a sudden, she shook her head, passionately, removed one arm from the wall and motioned me to go. And, when I could not bring myself immediately to obey, such a look of supplication, of imploring, came into her childlike eyes, that I could do nothing but turn away. As quickly as possible, I went on my way. Not once did I turn around. Not out of consideration—really—not out of obedience, not out of chivalry, but because, in our last glance, I had felt such an emotion as I had never before experienced, so that I almost swooned." And Fridolin was silent.

"And how often did you take the same road after that?" Albertine asked staring before her, her face devoid of expression.

"What I told you," Fridolin replied, "chanced to happen on the last day of our stay in Denmark. I, too, don't know what might have happened under other circumstances. Please, Albertine, don't ask any more."

He remained immobile at the window. Albertine rose and stepped towards him. Her eyes were moist and dark, her eyebrows slightly raised. "In the future we will tell each other these things immediately," she said.

He nodded.

"Promise me?"

He drew her to him. "Don't you know that?" he asked; but his voice was still strained.

SHE took his hands, stroked them and looked up to him with veiled eyes in the depths of which he was able to read her thoughts. Now she was thinking of his other, more real and youthful adventures of which she had gained knowledge. During the first years of their marriage Fridolin had far too easily yielded to her jealous curiosity and had confessed—and (as he often thought) even betrayed—things that he should have kept to himself. At this moment, he knew, many memories were forcing themselves on her and he was hardly surprised when, as if in a dream, she mentioned the half-forgotten name of one of his early loves, and it came like a rebuke—one might even say a threat.

He drew her hands to his lips.

"In every one—although it may sound trite for me to say so—in every one I thought I loved, believe me, I was seeking only you. 1 realize this far better than you can understand, Albertine."

She smiled sadly. "And if I had been the first to choose to go adventuring?" Albertine asked. Her glance changed, became cool, impenetrable. Fridolin let her hands glide from his own as if he had discovered her in a lie, in a betrayal; but she said: "Oh, if you only knew," and again she was silent.

"If you only knew—? What do you mean?" With a hardness unlike her, she replied: "Almost what you think, my dear."

"Albertine—then there is something which you have hidden from me?"

She nodded and looked straight ahead with a curious smile.

Vague, mad doubts awoke in him.

"I don't understand," he said. "You were hardly seventeen when we became engaged."

"Past sixteen, yes, Fridolin. And yet—" she looked straight into his eyes—"It wasn't my fault that I was a virgin when I married you." "Albertine—!"

AND she told her story:

"It happened at the Worthersee, a short time before our engagement, Fridolin. One beautiful summer evening a handsome young man came at my window which overlooked a great, wide meadow. We talked together and during our conversation I thought—yes, I must tell you what I thought: 'What an adorable, charming young man—he would only have to say one word (of course, it would have to be the right one) and I would join him on the lawn and would walk with him wherever he wished to go—perhaps in the woods—or lovelier still, we could take a boat out on the lake—and that night he could have had everything of me which he asked. Yes, that was what I thought. But the charming young man did not say the word: he only kissed my hand tenderly—and the next morning he asked me—whether l would become his wife. And I said yes."

Fridolin, annoyed, loosened his grip on her hand. "And if that evening," he said, "by chance, another young man'had stood at your window who had spoken the right word, for example—" He was debating which name to mention, when she stretched out her hand in protest.

"Another, whoever he might have been, could have expressed every desire—it would have availed him nothing. And had you not been the one who stood before the window"— she smiled up at him—"then the summer evening would not have been so beautiful."

Fridolin sneered: "So you say now, so you probably believe now. But . . ."

There was a knock. The maid entered and announced the arrival of the concierge from the Schreyvogelgasse who had come to fetch the doctor to the Hofrat who again had taken a turn for the worse. Fridolin went into the anteroom and learned from the cosicierge that the Hofrat had had a heart attack and was in a bad way; and Fridolin promised to go to the Hofrat*s house at once.

"Are you leaving?" Albertine asked as he prepared to go, and her voice had an annoyed tone—as if Fridolin were deliberately doing her an injustice.

Fridolin answered, a bit surprised: "You know I must go!"

She sighed softly.

"Let's hope it won't be so bad," Fridolin said. "Up to now three grains of morphine have always helped him over his attacks."

The maid had brought in his fur-coat; Fridolin kissed Albertine rather absent-mindedly on the forehead and lips as if the conversation of the last hour were already erased from his memory—then he rushed out.

II

ONCE on the street, Fridolin was forced to open his fur-coat. All at once it had begun to thaw, the snow on the sidewalks was almost gone, and the air held a breath of the coming spring. From Fridolin's house in the Josefstadt near the Allgemeinen hospital it was barely a quarter of an hour's walk to the Schreyvogelgasse; and soon Fridolin was walking up the poorly-lit winding stairway of an old house. On the second landing, he pulled a bell handle; but before he heard the ring of the old-fashioned bell, Fridolin noticed that the door was slightly ajar; he walked through the unlighted foyer to the living room and gathered that he had come too late. The greenshaded oil lamp hanging from the low ceiling threw a sickly light over the blanket under which a shrunken body lay motionless. The face of the dead man was in the shadow, but Fridolin knew it so well that he thought ho saw it in all its detail—thin, emaciated, with a high forehead, with a white, short beard, and unusually hairy ears. Marianne, the daughter of the Hofrat, sat at the foot of the bed, her hands hanging listlessly, as if tired. The room smelled of old furniture, medicine, oil and of the kitchen; also of a little eau de cologne, rose soap, and somehow Fridolin also sensed the dull sweet odour of this pale girl who was still young and who, because of years of heavy house work and exhausting nursing and night watches, was slowly wasting away.

When the doctor entered, she turned her glance at once on Him, but in the poor light Fridolin could hardly see whether her cheeks had flushed as usual on his arrival. She wanted to rise but with a motion he forbade her. With her big but sad eyes she greeted him. He stepped to the head of the bed, mechanically touching the forehead of the dead man whose arms, in wide open shirt sleeves, lay on the blanket. Then he shrugged his shoulders in mild pity, put his hands into the pockets of his fur coat, looked about the room and finally at Marianne. Her hair was thick and blond but dry, her throat well-shaped and long but not without wrinkles and it had a yellowish tint, and her lips were thin with many unspoken words.

(Continued on page 124)

Continued from page 52

"Well, well," he said in an almost abashed whisper, "this doesn't find you unprepared, dear child."

Marianne stretched out her hand to him. Fridolin took it consolingly, dutifully inquired after the final moments of the attack. She told him concisely and briefly, and then spoke of the last few comparatively good days during which Fridolin had not seen the patient. Fridolin had drawn up a chair. Sitting opposite Marianne, he again consolingly reminded her that her father in his last hours could hardly have suffered; then he asked whether her relatives had been informed. Yes; the concierge was already on her way to her uncle and no doubt Dr. Roediger, her fiance would arrive soon, she added, and looked at Fridolin's forehead rather than into his eyes.

Fridolin only nodded. During the past years, he had met Dr. Roediger twice or three times in this house. The painfully thin, pale young man with the short blond beard and glasses, instructor of history at the University of Vienna, had seemed congenial to him without interesting him. Marianne would certainly look better, he thought, if she were Roediger's sweetheart. Her hair would not be so dry and her lips would be redder and fuller. How old is she? Fridolin asked himself. When the Hofrat first called me in—three or four years ago —she was twenty-three. Then her mother was still alive. She was gayer when her mother was still alive. •Hadn't she studied singing for a short time? So she is going to marry this instructor after all? Why? She is surely not in love with him, and he hasn't much money either. What kind of a marriage will that be? Well, one like a thousand others. What business is that of mine? It is quite likely that I shall never see her again. From now on I have no official visits to make to this house. Oh, how many people I have never seen again who were far closer to me than Marianne!

While these thoughts were coursing through Fridolin's head, Marianne began to talk of the deceased—with a certain impressiveness as if the simple fact of his death had suddenly transformed the Hofrat into a great man. So he was only fifty-four years old? Of course, his many troubles and disappointments, his wife continually sick—and the son, too, had caused him to worry much! What, she had a brother? Certainly. Hadn't Marianne told Fridolin about it once before. Her brother now lived in some foreign land. In Marianne's boudoir hung a picture of him at the age of fifteen. An officer riding down a hill. Father had always acted as if he didn't see the picture at all. It was a good picture. Under more favourable circumstances, her brother would have made a name for himself.

How excitedly she talks, Fridolin thought, and how her eyes sparkle. Fever? Possibly. She has grown thinner lately. Probably a tendency to consumption.

She rambled on and on, but it seemed to Fridolin as if she were not very conscious to whom she was talking; or as if she were talking to herself. Her brother had been gone for twelve years, yes, she was still a child when he disappeared suddenly'. They had last heard of him four or five years ago at Christmas time. From a small town in Italy. Strange, she had forgotten the name. For a little while Marianne talked of unimportant things—quite irrationally, almost incoherently, then she stopped suddenly and sat in silence, her head in her hands. Fridolin was tired and bored.

Casting a hasty sidelong glance in the direction of the dead man, he said: "After all, as things are now, I am glad, Miss Marianne, that you won't have to stay in this house much longer."

"We shall move in the fall," she replied without stirring. "Dr. Roediger has been called to Gottingen."

"Ah," said Fridolin, and tried to congratulate her, but it seemed rather inappropriate at the moment and in this surrounding. He looked at the closed window and, without asking for permission, and as if doing something which, as a doctor, he had a right to do, he opened it wide and let the air come in which, warmer and balmier than before, seemed laden with a soft perfume of stirring, faroff woods. When he turned around towards the room again, he met Marianne's eyes, looking questioningly at him. Fridolin stepped near her and said: "I hope the fresh air will do you good. It has grown warm and last night"—he almost said: we drove back from the Redoute in the snow, but he quickly revised the sentence and remarked: "Last night the snow was still half a metre high in the streets."

Marianne hardly heard what he said. Her eyes grew moist, big tears rolled down her cheeks, and once more she buried her face in her hands. Without thinking, he put his hand on her hair and stroked her forehead. He felt her body trembling, she sobbed inaudibly at first, gradually louder, finally without restraint. Then she slid down from her chair, lay at Fridolin's feet, clasped his knees in her arms, and pressed her face against them. She looked up at him and with wide open, grief-stricken eyes, whispered fervently: "I don't want to leave here. Even if you never come again, if I never see you again: I want to live near you."

He was more touched than surprised; for he had always suspected that she was in love with him, or believed herself in love with him.

Continued on page 126

Continued from page 124

"Get up, Marianne," he said softly, bent down to her, carefully helped her rise and thought: of course, there is much hysteria in this, and he shot a sidelong glance at the dead father. I wonder whether he hears everything —the idea rose to his mind. Perhaps he isn't really dead. Perhaps no one in the first hours after death is really dead? He held Marianne in his arms, but at the same time pressed her away from him, and almost involuntarily kissed her on the forehead. It all seemed to him rather ridiculous. Apropos, he recalled a novel he had read years before in which it happened that a young man, almost a boy, at the deathbed of his mother, had been seduced by a friend of hers. At the same moment, he didn't know why, Fridolin was impelled to think of his wife. A bitterness against her rose in his heart and at the same time a halfconscious anger against a gentleman in Denmark with a yellow handbag who stood on the staircase of the hotel. He drew Marianne closer but did not feel the slightest excitement. Rather, the sight of her dull, dry hair, the sweetish odour of her unaired dress, repelled him a trifle. The outside bell rang. Fridolin felt relieved, quickly kissed Marianne's hand as if in gratitude and went to open the door. It was Dr. Roediger standing in the doorway with his dark gray Inverness, rubbers, and umbrella in his hand, and —of course—with an appropriately sad expression on his face. The two men nodded a greeting to each other, more friendly than was justified by their slight acquaintance. Then together they entered the room. Roediger, after a timid glance at the dead man, expressed his sympathy to Marianne; Fridolin went into the next room to write out the death certificate, turned the gas flame over the table higher, and his glance fell on the picture of an officer in a white uniform who, with his sabre drawn, was riding down a hill in the direction of an invisible foe. It was in a small, gilt frame, and did not look much better than a cheap print.

With the death certificate filled out, Fridolin re-entered the other room where, at the father's bed, the betrothed couple sat, their hands intertwined.

Again the bell rang, Dr. Roediger rose and went to open the door; meanwhile Marianne said almost inaudiblv, with her glance fixed on the floor: "I love you." Fridolin's response was to pronounce Marianne's name not without tenderness. Roediger returned with an elderly couple. Marianne's aunt and uncle; they exchanged a few appropriate words with all the embarrassment which the presence of the dead usually evokes. The small room suddenly appeared crowded with mourners, Fridolin felt himself superfluous, took leave, and was ushered to the door by Dr. Roediger who felt obliged to say a few words of gratitude and to express a desire to see Fridolin soon again.

Fridolin, in front of the house door, looked up at the French windows he had opened himself; both panes were trembling slightly in the early spring wind. The people who had remained behind up there,—living as well as dead—seemed equally ghostlike and unreal to him. He himself felt as if he had escaped; not so much from an adventure as from a melancholy witchery, the power of which he feared. The after-effect was that Fridolin had acquired an odd aversion to going home. The snow in the streets had melted away, left and right small, dirty white heaps were piled up, the gas flames in the lanterns wavered, from a nearby church it struck eleven. Fridolin decided to spend half an hour in a quiet cafe on the corner near his home. And so he made his way through the Rat/iaus park. On the dark benches couples sat here and there, closely pressed in each others'arms, as if it were really Spring and as if the warmth of the air were not deceptive and teeming with danger. On one bench lay a tramp, his hat pulled down over his forehead. If I woke him up, thought Fridolin, and gave him money for a night's lodging? Ah, what good would that do, he mused, tomorrow I would have to take care of him, too, otherwise it would be senseless, and in the end I might even be suspected of a personal interest. And he hurried the quicker, to avoid any kind of responsibility or temptation. Why pity him, Fridolin asked himself, there are thousands of poor devils like him in Vienna. If one were to worry over all of them, —worry over the fortunes of all these unknowns! And he thought again of the dead man, the corpse he had just left, and with a slight shudder, tinged with disgust, Fridolin remembered the long, prone, thin body under the brown flannel blanket in which, according to eternal laws, decomposition and decay had already set in. And Fridolin rejoiced that he was still alive, that, for him,—in all likelihood—these ugly things were still far removed; that he was still in the prime of life, that he had a charming and lovable woman as his own, and that he could have one or several others besides her if he so desired. For such affairs, of course, one would require more leisure than was his lot; and he remembered that tomorrow morning at eight o'clock, he would have to be in his ward, that from eleven until one he must call on private patients, that in the afternoon from three till five he must keep office hours, and that even in the evening he would have to make several visits. Fridolin hoped at least that he would not be disturbed again in the middle of the night as he had been today.

He crossed the Rat/iausplalzy dimly aglow like a brown pond, and turned towards his own district, the Josefstadt. From afar he heard dull, regular footsteps and saw, still from a distance, just turning a corner, a small group of fraternity men, six or eight of them coming towards him. When the young people came under the reflection of the lamp, he thought he recognised the blue caps of the Alemannen. He himself had never belonged to a fraternity but in his time he had fought a few duels with sabres. Memories of his own student days made him think of the red dominoes of the night before who had tempted him into their box only to leave him so unceremoniously. The students were quite near, they talked volubly and laughed—perhaps he knew one or two who were internes at the hospital? But in the dim light it was not possible to make out the faces distinctly. Fridolin had to keep close to the wall in order not to bump into them;—now they had passed; only the one at the end, a tall fellow with an open overcoat and a bandage over his left eye, seemed to lag behind deliberately, and with outspread elbows knocked against him. Not an accident, surely. What was wrong with the fellow, thought Fridolin, and stopped involuntarily; after two more steps the student did the same and, for a moment, a short distance apart, they glared at each other. Suddenly, however, Fridolin turned about and walked ahead. He heard a short laugh from behind—he was about to turn around once more to challenge the boy when he felt a strange fluttering of the heart—a fluttering such as he had experienced twelve or fourteen years ago when someone had knocked furiously at his door while lie was entertaining a charming young girl who always loved to talk of a distant (probably non-existent) fiance; as a matter of fact, it had only been the letter carrier who had knocked so threateningly. Just as at that time he had felt his heart jump, he felt it now. What's wrong? he asked himself a bit angrily, and Fridolin noticed that even his knees were trembling a bit. Cowardly? Nonsense, he thought. Shall I stand here with a drunken student, I, a man of thirty-five years, a practising physician, married, the father of a child—challenge! witness! duel! And in the end possibly a sabre wound in the arm on account of a stupid insult? Incapacitated for a few weeks —or the loss of an eye?—or even blood poisoning? And within a week to be like the man in the Sc/treyvogelgasse—under a blanket of brown flannel! Cowardly? He had fought three duels with sabres and he had once even been prepared to go through with a duel with pistols, and it was not at his demand that the affair had been called off. And his profession! Dangers on all sides and at all times —only one forgot them—regularly. How long ago that a child, a diphtheria victim, had coughed into his face: Three or four days, not longer. This, after all, was a much more important matter than an unimportant sabre duel. And he had simply not thought of it again. Well, if he met the fellow again the affair could still be cleared up. Under no circumstances was he obliged at midnight on his way from a sickbed or to a patient, (this after all could also have been the case) no, he was really not obliged to notice such a stupidity. If, for example, the young Dane were to come his way, with Albertine—oh, no, of what was he thinking? Well— after all, it was not very different than if she had been his sweetheart. Worse yet. Yes, he would like to meet the Dane now. It would be a real pleasure to stand opposite him in a clearing in the forest and to point the barrel of a pistol at the forehead with the smooth blond hair.

Continued on page 130

Continued from page 126

All of a sudden Fridolin found himself already beyond his goal in a narrow street, where a few poor street-walkers were on their nightly rounds. Wraithlike, he thought. And then the students with their blue caps seemed to become ghostlike in his memory,—so did Marianne, her fiance, the uncle and aunt, whom he imagined encircling the death-bed of the Hofrat; so did Albertine as well, who in his mind's eye was deep in sleep, her arms folded under her neck—even his child, who now lay rolled up in her little brass bed and the red-cheeked governess with the birthmark on her left temple—they all seemed to him completely ghostlike. And in so regarding them (although it made him shudder a bit) there was at the same time something soothing, which seemed to lift a load from his mind and even to sever him from all human relationship.

One of the loitering girls invited him to come along. She was rather fragile, still very young, very pale with bright red lips. This might also end in death, Fridolin thought, only not a quick death? Again cowardice? Basically yes! He heard her steps and her voice behind him. "Come along, doctor?"

Automatically he turned around, "How do you know me?" he asked.

"I don't know you," she said, "but in this district they are all doctors."

Since his high school days lie had had nothing to do with a girl of this type. Was it because he had suddenly reverted to his youth that this girl tempted him? He remembered a casual acquaintance, a young man about town, who was known for his astounding luck with women, and with whom he had once sat in a night club, after a ball, and who, before he left with one of the girls "in the profession" had answered Fridolin's somewhat surprised look with the statement: "This is always the most comfortable thing and they are really not the worst kind."

"What is your name?" Fridolin asked.

"Well, what would I be called? Mizzi, of course." She had already turned the key in a house-door, entered the vestibule and waited for Fridolin to follow.

"Hurry up," she said when he hesitated. Suddenly he found himself next to her, the door closed behind him, she locked it, lit a small candle and showed him the way—Am I crazy? he asked himself. Of course I won't have anything to do with her.

A small oil lamp was burning in her room. She turned the wick higher, it was quite a comfortable room, neatly kept and at any rate, the smell was more agreeable here than, for instance, in Marianne's home. Of course—no old man had lain here bed-ridden for months. The girl smiled, approached Fridolin without any show of forwardness, but he gently held her off. Then she pointed to a rocking chair in which Fridolin gratefully sank down.

Continued on page 134

Continued from page 130

"You must be all in," she ventured. He nodded.

"Yes, a man like you—you certainly work hard all day. That's where we get off easy."

He noticed that her lips were not rouged at all, but were naturally red and complimented her on it.

"Why in God's name should I make up?" she asked. "How old do you think I am anyhow?"

"Twenty," Fridolin ventured.

"Seventeen," she said. She sat on his lap and threw her arms around his neck like a child.

Who in the world would imagine, he thought, that at this moment I would be in this room? Would I have believed it possible an hour, even ten minutes ago? And—why? Why? She searched for his lips with hers, but he drew back. She looked at him, a little sadly and let herself slide from his lap. He almost regretted it, for in her embrace there had been much consoling tenderness.

"Do you like that better?" she asked, without sarcasm—bashful, as if she were trying hard to understand him. He hardly knew what to answer.

"You guessed right," he said, "I'm really tired and I find it very pleasant to sit here in the rocking chair and to listen to you. Y'ou have such a soft voice. Talk, tell me something."

She sat on the bed, shaking her head.

"You're simply scared," she said softly—and then under her breath, hardly audibly, "it's too bad!"

These last words sent a hot wave through his blood. He stepped nearer to her, tried to embrace her, explained that he trusted her completely, and in saying so even spoke that which was truth. Fridolin drew her close, treated her as if she were a virgin, like a woman he loved. She resisted. Ashamed, he finally gave up.

The bank-notes which he offered, she refused with such firmness that he did not try to persuade her. She took a small blue wool shawl, lit a candle, showed him the way out, then led him downstairs and unlocked the door. "I guess I'll stay home to-night," she said. He took her hand and kissed it. She looked up surprised, almost shocked, then she laughed shyly and happily. "Like a lady," she said.

The door closed behind him and with a quick glance Fridolin impressed the •number on his mind, so that he might be able to send the poor child wine and sweets.

Meanwhile it had grown a little warmer. A mild wind swept the fragrance of damp meadows and the spring of the faraway mountains into the narrow street. Where now, thought Fridolin, as if it were not the obvious thing finally to go home and to bed. But he could not bring himself to it. He seemed to himself homeless and exiled, since his disagreeable encounter with the d lemannen students . . . orwas it since Marianne's confession of love? No, still longer—since the last evening's talk with Albertine, he had wandered further and further away from the accustomed realm of his existence into some other far and strange world. This way and that, he made his way through the dark streets, permitted the light wind to caress his forehead and finally, with decisive steps, as if he had finally reached a long-looked for giJtil, he entered a cafe of the shabbiest kind, but which had an old Viennese warmth, although it was not particularly roomy, and was dimly lighted, and poorly patronized at this late hour.

In a corner three men were playing cards; a waiter who had been watching the game until then, helped Fridolin off with his fur-coat, took his order and put the illustrated magazines and evening papers on the table. Fridolin felt safe at last and casually began to look through the papers. Here and there his attention was captured. In some Bohemian city, German street signs had been torn down. In Constantinople there had been a conference regarding the construction of a railroad in Asia Minor, in which Lord Cranford participated. The firm of Benis and Weingruber were bankrupt, the prostitute, Anna Tiger, had in a fit of jealousy thrown vitriol at her friend, Hermine Drobisky. This evening there was to be a "Herring Bake" in the Sofiensalen. A young girl, Marie B., Schonbrunnerhauftstrasse, 28, had poisoned herself with bichloride of mercury—all these facts, the trivial and the tragic, in their dry matter-of-factness sobered and quieted Fridolin. The young girl, Marie B., captured his sympathy; bichloride of mercury—how silly! At this moment as he sits comfortably in the cafe and Albertine sleeps peacefully with her arms folded under her neck and the Hof rat was already beyond all earthly sorrow, Marie B., Schonbrunnerhauftstrasse^ 28, was writhing in futile pain.

He looked up from his paper. From the table opposite he saw two eyes gazing at him. Was it possible? Nachtigall—? He had already recognized him, raised both arms in pleasant surprise. A big, rather broad, almost fat, still young, man, with long slightly curly blond, already somewhat gray, hair and a blond moustache drooping in Polish fashion, came over to Fridolin. He wore an open gray Inverness, and under it a somewhat shabby dress suit, a crumpled shirt with three imitation diamond studs, a wilted collar and a flowing white silk tie. His eyelids were red from many wasted nights, but the eyes sparkled gay and blue.

"You are in Vienna, Nachtigall?" burst out Fridolin.

"You don't know," said Nachtigall in his soft Polish accent, with slightly Jewish intonation.

"How come you don't know? Ain't I famous enough for yer?" He laughed loudly and good-naturedly and sat down opposite Fridolin.

"Did you secretly become a professor of surgery?" asked Fridolin. Nachtigall laughed more boisterously; "You didn't hear me just now?"

"How so? Oh, yes." And only now Fridolin realized that as he entered, even before he entered—as he approached the cafe,—he had heard the sound of piano playing emerging from the depths of a cellar.. "So that was your" cried Fridolin.

Continued on page 136

Continued from page 134

. "Sure, who else?" Nachtigall laughed.

Fridolin nodded. Naturally—the peculiarly energetic touch, those strange, wayward, hut tuneful harmonies of the left hand, had seemed familiar to him from the very beginning. "So this is what you're doing now?" he said. He recalled that Nachtigall had given up the study of medicine on passing his second examination in zoology—seven years late, it is true. But for some time after the examinations, Nachtigall had idled about in the operating room of the hospital, in the laboratories and class rooms. Everywhere his blond artist's head, his perpetually wilted collar, and his flowing, once white tie, had made Nachtigall a striking and lovable figure, popular not only with his fellow-students but also with some of the professors. The son of a Jewish saloon keeper, in a small Polish village, he had come to Vienna to study medicine. The small allowance from home was not even worth mentioning, at the beginning, and was soon entirely discontinued, which did not prevent Nachtigall's regular presence at the Stammtisch of the medical students at the Ried/iof, to which Fridolin also belonged. From that time on his bills were paid by one or the other of the wealthy students. He also inherited, occasionally, pieces of clothing, which he accepted gladly anil without false pride. In his small home town lie had learned, from a stranded pianist, the fundamentals of piano playing, and in Vienna, as a stmliosus medicinae he also attended the Conservatory where he was considered a promising pianist. But Nachtigall was not earnest or industrious enough to study regularly; and soon enough his musical success in the circle of his friends (or rather the pleasure he gave them with his piano playing) sufficed him. For a time he worked as a pianist in a suburban dancing school. His fellow students and table companions tried to get him into the better homes in the same capacity, but on these occasions he played only what he pleased, and as long as he pleased, entered into conversations with young ladies, which, on his part, were not always innocent and invariably drank more than he could stand. Once* he played for a dance at the home of a bank director. By midnight he had embarrassed the voupg girls who danced by him through his pointedly provocative remarks and had antagonized their partners. On an impulse he began to play a wild can-can and to sing a questionable couplet in a powerful bass voice. The bank director gave him a calling down. Nachtigall, as if consumed with blessed gaiety, rose and embraced the director, who, thereupon, cursed Nachtigall roundly. In spite of the fact that the director was a Jew himself, he hurled a marked insult, which Nachtigall returned with a resounding box on the ear—and thus his career in the better houses of the city appeared definitely over. In more intimate circles he behaved more decently, even though it was occasionally necessary, at a late hour, to throw him bodily out of the room. But the next jnorning speh interludes were forgotten and forgiven by all those present. One day when all the other students had long since finished their studies, Nachtigall suddenly disappeared from the city without saying good-bye. For a few months afterwards postcards from him arrived from various Russian and Polish cities; and once, without further explanation, Fridolin, whom Nachtigall had taken to his heart, was not only reminded of his existence by a card, but also by a request for a small loan. Fridolin sent the money off without delay, and never received so much as a thank you or any other sign of life from Nachtigall.

At this moment, however, a quarter to one at night, eight years later, Nachtigall insisted on making good his long neglected debt immediately. He took the exact sum in notes from his rather dilapidated pocketbook, which, however, was well enough filled so that Fridolin could accept the money without pangs of conscience. . . .

"So everything is all right with you," he said smilingly, as if to calm his doubts on the subject.

"I can't complain," replied Nachtigall, putting his hand on Fridolin's arm; "but now tell me where do you come from at this hour of night?"

Fridolin explained his presence at this late hour by an urge to have a cup of coffee after a late professional call; but he did not mention, without knowing just why, that he had found his patient dead. Then Fridolin talked, in general, about his work at the Polyclinic and about his private practice, mentioning that he was happily married and father of a six-year-old girl.

Then Nachtigall told his story. As Fridolin had guessed, he had made a living all these years as a pianist in all kinds of Polish, Roumanian, Serbian and Bulgarian cities and towns, in Lemberg his wife and four children lived—and Nachtigall laughed lightly, as though it were very funny to have four children, all in Lemberg and all of one and the same woman. He had been in Vienna since the previous autumn. The music hall, which had engaged him, went into bankruptcy immediately and now he played in various places, as the opportunity arose. Sometimes, in two or three of them in a night— here, for example in a cellar—not a very high class establishment, as one could notice, rather a sort of bowlingalley, but, as far as the public was concerned. . . .

"But if you have to take care of four children and a wife in Lemberg"—Nachtigall laughed again but not quite as merrily as before. "Sometimes I have private engagements," he added quickly. And when he saw a knowing smile on Fridolin's face— "Not at the homes of bank-directors and such. No, in all kinds of places, large and pliblic and secret."

"Secret?"

Nachtigall looked knowing. "I'll be called for in a minute."

Continued on page 138

Continued, from page 136

"What—you'll play again tonight?"

"Yes, there they don't start before two."

"A particularly fashionable place?" said Fridolin.

"Yes and no," laughed Nachtigall, but immediately became serious again.

"Yes and no—?" repeated Fridolin curiously.

Nachtigall bent over the table towards him.

"Tonight I am playing in a private house—I don't know whose."

"Then you're playing there for the first time tonight?" asked Fridolin with growing interest.

"No, the third, but it'll probably be another house again."

"I don't understand."

"Nor me," laughed Nachtigall, "better not ask."

"Hmm," said Fridolin.

"You're all wrong. Not what you think. I've seen a lot—you wouldn't believe—in these small cities, mostly in Roumania—you see so much, but here. . . ."

He pushed back the yellow curtain, looked out at the street and said half to himself:

"Not here yet,"—and then to Fridolin, in explanation, "I mean the carriage. Always a carriage calls for me—always a different one."

"You arouse my curiosity, Nachtigall," Fridolin said coolly.

"Listen to me," said Nachtigall after some hesitation. "If I wanted to do good by someone—but how can one do it—" and suddenly: "Have you courage?"

"Strange question!" said Fridolin in the tone of an army officer who has just been offended.

"I didn't mean it that way."

"How did you mean it, then? Why is courage essential for this particular occasion? What can happen?" And Fridolin laughed curtly and disparagingly.

"Nothing can hurt me, the worst is that maybe I play for the last time today—but this might happen anyway." Nachtigall stopped and peered again through the opening in the curtain.

"Well then?"

"What do you mean?" Nachtigall asked as if in a dream.

"Go ahead. Once you've started . . . Secret affair? Closed affair? Invited guests only?"

"I don't know. Last time there were thirty people. The first time only sixteen."

"A ball?"

"Sure, a ball." And now he seemed to regret that he had spoken at all.

"And you provide the music?"

"For it? I don't know for what. Honest, I don't know for what. I play, I play—blindfolded."

"Nachtigall, Nachtigall, what kind of a yarn arc you telling!"

Nachtigall sighed. "But,, worse luck, not all blindfolded. Not so much that I can't see something. You see, I can look into the mirror through the black silk handkerchief over my eyes . . ." And again he stopped.

"In one word," Fridolin said impatiently and irritably while he felt oddlv excited. . . . "Women."

"Don't say women, Fridolin," replied Nachtigall as if offended. "You've never seen such creatures."

Fridolin cleared his throat. "And how much is the admission?" he asked casually.

"Tickets, you mean, and such? What are you thinking of?"

"How do you get in, then?" Fridolin asked through closed lips and drummed on the table.

"You must know the password, and always it's something else."

"And to-day's?"

"Don't know. The driver tells me."

"Take me with you, Nachtigall."

"Impossible. Too dangerous."

"A minute ago you thought of it yourself. ... If you wanted to do good by some one! You can arrange it."

Nachtigall looked at him searchingly. "As you are—you couldn't, anyway, everyone is masked, gentlemen and ladies. Have you a mask with you, or anything? Impossible. Perhaps next time. I'll think out something." He listened and peered again through the crack in the curtain out at the street, and breathing more freely: "Here's the carriage. Goodbye."

Fridolin held him by the arm. "You can't leave me this way. You must take me along."

"But, Kollega . . .

"Leave everything else to me. I realize that it's 'dangerous'—perhaps it's just that which tempts me."

"But I just told you—without a costume and mask—"

"There are places to rent costumes."

"At one in the morning—"

"Listen to me, Nachtigall. At the corner of Wickenburgstrasse I know a place. I pass the sign every day." And quickly, with growing excitement: "You wait here another fifteen minutes, Nachtigall, while I try my luck there. The owner of the place probably lives in the house. If not— then I'll give up. Let Destiny decide. In the same building is a cafe, Cafe Windobona I think it's called. You tell the driver—that you've left something there, come in, I'll be waiting near the door, you give me the pass word quickly, return to your carriage; if I succeed in getting a costume immediately, I take another cab, follow you—the rest will take care of itself. Your risk, Nachtigall, on my word of honour, I take upon myself."

Nachtigall had repeatedly tried to interrupt Fridolin but in vain. Fridolin threw the money on the table, leaving an extravagant tip, which seemed quite in keeping with the spirit of the night, and left. Outside he saw a closed carriage, the driver on his seat, motionless, all in black, with a high top hat;—like a funeral cortege} thought Fridolin. After a few minutes of hastening he reached the corner house he was seeking, rang the bell, asked the concierge whether the costumer Gibiser lived there, and secretly hoped he might be told no. But Gibiser did live there,—the concierge did not seem surprised over the lateness of the call. On the contrary. In good spirits as a result of his large tip, the concierge remarked that in carnival time it was by no means unusual for people to come at this late hour of the night to hire costumes. From down below he held the candle long enough for Fridolin to ring the bell at the first landing. Mr. Gibiser, one might suspect, had been waiting behind the door. He opened in person—thin, beardless, bald, wear. ing an old-fashioned flowered dressing gown and a Turkish fez with a tassel which made him look like a stage comedian. Fridolin explained his mission and remarked that price was no object, whereupon Mr. Gibiser waved this aside and said, "I ask what is due me, no more."

Continued on page 142

Continued, from page 138

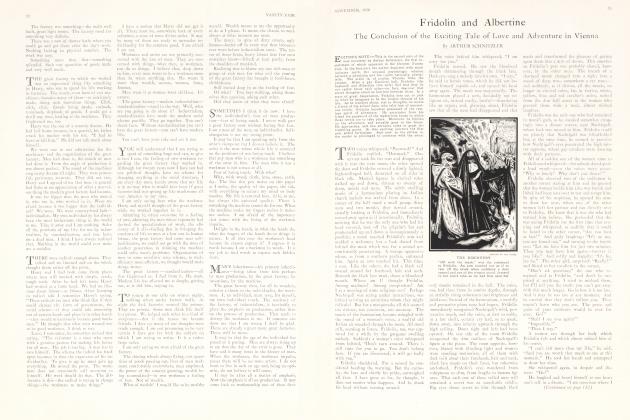

He led Fridolin up a winding stairway into his storeroom. It smelt of soap, velvet, perfume, dust, and withered flowers; from the indistinct darkness silver and red gleamed} and all at once small lamps shone between open chests along a narrow, long corridor which lost itself in the darkness. Right and left hung costumes of all kinds} on the one side knights, pages, peasants, hunters, scholars, Orientals, jesters} on the other, court ladies, ladies-in-waiting, peasant women, servant girls, Queens of the Night. Above the costumes were the respective headdresses and Fridolin felt as if he were walking through an alley of hanged, about to join each other in a dance. Mr. Gibiser walked behind Fridolin. "Has the gentleman any particular desire? Louis Quatorze? Directoire? Altdeutsch?"

"I want a dark monk's cowl and a black mask, nothing else."

At this moment from the end of the passageway glasses clinked. Frightened, Fridolin looked into the face of the costumer as if he should be vouchsafed an immediate explanation. But Gibiser himself stood rigid, reached for a concealed switch—and brilliant light poured down to the end of the corridor where a small table, set with plates, glasses, and bottles, could be seen. From two chairs, left and right, rose two knights, of the Secret Fetne in their scarlet robes while at the same time a fair, fragile being was seen to disappear. With long steps Gibiser rushed down, reached over the table, and grabbed a white wig at the moment that a charming, very young girl, almost a child, dressed in a Pierrette costume, with white silk stockings, flew down the passageway towards Fridolin who involuntarily caught her in his arms. Gibiser had dropped the wig on the table and now held the Knights of the Feme by the folds of their gowns. At the same time he shouted to Fridolin, "Please, sir, hold the girl for me." The little one pressed herself against Fridolin as if she were seeking protection. A tiny slender face was white with powder, and dotted with several beauty spots. From her tender breasts rose the fragrance of roses and powder; her eyes gleamed with artfulness and desire.

"Gentlemen," Gibiser said, "you remain here until I call the police."

"What's wrong with your" they cried, in unison, as if the words came from one mouth: "We only accepted the lady's invitation."

Gibiser released them and Fridolin heard him say: "You'll have to explain a bit more than that. Or didn't you realize right off that you had a crazy person in tow?" And then to Fridolin: "Please pardon the interruption."

"Not at all," said Fridolin. He would have liked either to stay or to take the girl with him, wherever he went—and whatever the consequences. She looked alluringly and naively up to him, as if entranced. The Knights of the Fetne at the end of the alley talked excitedly to each other; coldly Gibiser spoke to Fridolin. "You wished a cowl, sir, a pilgrim's hat, and a mask?"

"No," said Pierrette, writh shining eyes, "You must give this gentleman a cloak of ermine and a red silken robe."

"Don't move from my side," said Gibiser to her, and pointed to a dark cowl hanging between a soldier and a Venetian senator. "That's your size, here's your hat, take them quickly."

Again the Knights of the Feme became audible. "Let us go this very moment, Mr. Chibisier," they pronounced Mr. Gibiser's name, much to Fridolin's surprise, in the French fashion.

"I wouldn't think of it," the costumer replied mockingly. "For the time being. Be good enough to wait here for my return."

Meanwhile Fridolin slipped on the cowl, knotted the loose ends of the white rope, and, standing on a small ladder, Gibiser handed him the black, broad-brimmed hat, and Fridolin put it on; but he did all this as if impelled, for more and more strongly he felt the need to remain here and rescue Pierrette from impending danger. The mask which Gibiser now pressed into his hand and which he tried on immediately reeked of a strange, somewhat repellent perfume. . . .

"You go on ahead," said Gibiser to the little one, and pointed to the staircase. Pierrette turned around, looked towards the end of the alleyway, and waved a gay farewell in which, none the less, one could detect sadness. Fridolin followed her glance; there were no longer any Knights of the Feme) instead two tall young men in evening clothes and white ties, but both still had red masks over their faces. Pierrette floated down the winding stairway. Gibiser walked down behind her and Fridolin followed. Downstairs in the foyer Gibiser opened the door leading to the inner rooms and said to Pierrette: "Go to bed at once, you miserable creature. I'll talk with you when I'm through with these gentlemen."

She stood in the door, white and tender, and with a glance at Fridolin she shook her head mournfully. In a large mirror at the right Fridolin saw an emaciated pilgrim—himself, of course,—and was amazed at thi naturalness of all this.

Pierrette had disappeared, the old costumer locked the door behind her. Then be opened the main entrance and shoved Fridolin out on the landing.

Continued on page 144

Continued from page 142

"Pardon me," said Fridolin, "but w hat do I owe you . . . ?"

"Never mind, sir, you pay when you return. I trust you."

But Fridolin did not move from the spot. "Swear to me that you won't harm the poor child:"

"What business is that of yours, sir: "

"I heard you speak of her as 'crazy' a little while ago—and now you call her a 'miserable creature.' A contradiction in terms, you must admit."

"No, sir," replied Gibiser with a theatrical gesture, "isn't the crazy one a miserable creature in God's eyes: "

Fridolin trembled in disgust.

"As usual," Fridolin remarked, "we'll find a way out. I'm a doctor. We'll continue our discussion tomorrow."

Gibiser laughed mockingly and soundlessly. On the staircase the light suddenly blazed. The door between Gibiser and Fridolin closed and the latch key was turned. While descending the stairs Fridolin removed the hat, cowl, and mask, made a bundle under his arm, the concierge opened the door, the funeral cortege with the motionless driver on the seat was still standing opposite.

Nachtigall was just about to leave the cafe and was not at all agreeably surprised that Fridolin had come on time.

"So you really got your costume,

"As you see. And the password?"

"You insist?"

"Absolutely."

"All right. The password is 'Denmark'."

"Are you crazy, Nachtigall?"

"Why crazy?"

"Nothing, nothing.—I happened to spend last summer on the coast of Denmark. Get in—but not immediately so that I'll have time to find a cab for myself."

Nachtigall nodded, slowly lit a cigarette, meanwhile Fridolin quickly crossed the street, hailed a cab, and in an innocent voice, as if it were all a joke, he told the driver to follow the funeral carriage which was just about to start.

They went along the AIserstrasse, passed under a railroad bridge, towards the suburbs, and on through badly lighted empty side streets. It occurred to Fridolin that the driver of his cab might lose sight of the other; but as often as he put his head out through the open window into the unnaturally warm air, he always saw the other carriage a short distance ahead, the driver with his high back top hat sitting motionless in his seat.

This may end badly, thought Fridolin. And all the time he smelt the odour of powder and roses which had risen to him from Pierrette's breasts. What weird romance have I been witness to? he asked himself. I should not have left. I ought not to have left. Where am I now'?

Slowly ascending, between small cottages, they drove on. Now Fridolin believed he knew where he was; years ago he had come across this neighbourhood while walking; this must be the Galizin hill they were now going up. To the left below him he saw a city of a thousand lights gleaming through the mist. He heard a rumble of wheels behind him and looked back through the window. Two carriages were following them, and he was glad as it would divert the driver's suspicion from him.

Suddenly the carriage, with an abrupt swerve, turned the corner and, between fences, walls, and abysses, the road descended. It occurred to Fridolin that it was about time to put on his costume. He took off his fur coat and slipped on the cowl just as every morning in the clinic he changed into his white hospital coat. And— a redeeming thought—Fridolin remeiYibered that only a few hours more and, if everything went well, he would be walking about between the beds of his patients just like every other morning—a helpful physician. The carriage stopped. Wouldn't it be better, Fridolin thought, if I didn't get out at all, but went right back? But where to? To little Pierrette? Or to the little street-walker in the Bitchfeldgasse? Or to Marianne, the daughter of the dead man? Or home? And with a slight shudder he realized that he had less desire to go home than anywhere else. Or was it because that way seemed the longest? No, I can't go back, he thought to himself. Onward, even unto death. Fridolin laughed at the grand phrase, but all the same he was none too gay.

A garden gate stood wide open. The funereal carriage ahead of him drove lower down into the gorge or rather into the darkness which seemed to be that. Nachtigall had probably already alighted. Fridolin quickly jumped from his cab, asked the driver to wait for him at the bend of the road, no matter how long he might be. And to make sure of him, Fridolin paid him in advance and promised him an equal amount for the return trip. The carriages which had followed pulled up. From the first one, Fridolin saw the huddled up figure of a woman emerge; then he entered the garden, put on his mask, a narrow path lighted from the house led him to the door. The doors swung open and Fridolin found himself in a small white foyer. He was greeted by the sound of a harmonium, two servants in dark livery, gray masks on their faces, stood right and left.

(Concluded in the November Issue)

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now