Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowHow to Produce a Sure-Fire "Flop"

GEORGE M. GOWAN

PLAY WRITING is a disease. And you have it. Oh, yes, you have. How about that manuscript lying at the bottom of the old, battered trunk: And the other one you work at on odd Thursday nights: Why, of course. In you the ailment lies dormant most of the time, but. every now and then it becomes acute.

During these attacks, you exhibit typical symptoms such as disgruntled discussion of the Stage of Today, vehemently expressed assurances that anybody ought to be able to do better than the feller that wrote S itchand-Such, and a sort of general rash of unrecognized genius breaking out all over the body. There really ought to be a Pest-house for your confinement. during these times, but unfortunately no legislation has been passed as yet. to further that project. Hence you are permitted to roam at will, indicting your "ideas" upon everyone within hearing distance, and ruining your own peace of . mind, sleep and appetite.

For the public good, as well as for the sake of your own happiness, would it not be a boon to be rid forever of the dread malady, Playwright's Itch: Follow my instructions, and you will achieve a cure, once arid for all. GET YOUR PLAY PRODUCED.

Ay, produced. But how: I la, there is the secret. Not successfully ; for if you should happen upon a long run and considerable royalties, nothing in the world could prevent the disease from becoming chronic, and in a state of continual virulence. You would simply keep on writing plays the rest of your life, and what would become of the delicatessen, the rags-and-old-iron or the bond business then: Not even what is known as an "artistic success"—i.e., seven or eight week's run,—will in any wise relieve you. No, a complete cure can be accomplished only in one way—by an all-around, unmistakable fiasco. If, after following the regime I shall recommend hereunder, you still have any desire to manufacture dramas, a running dive into the most proximate body of water is the only alternative to a life of anguish and shame. Ninety-nine chances out of a hundred, however, a resounding flop will not only settle most of your longings, it will contribute to the general hilarity, and you will shine forth as something in the nature of a public benefactor.

Now, in preparing for your cataclysm, remember that as Goethe, or Carlyle, or somebody said, "The play's the thing." And for a first class bloomer, a good play is a decided advantage to start with. However, if your play is mediocre, or even decidedly poor, bear in mind that some excellent failures have been made even out of plays that were perfectly awful—Abie's Irish Rose and Aloma of the South Seas to the contrary, notwithstanding. The soundest advice I can give you is this: write your besty and let the producer take care of details.

First, then, write your "script". Then rewrite it. Evcy time you read it over, rewrite it again. Repeat this process until you arc convinced that you have something practically perfect. Then show it to various friends. You will be given advice. (Will you!) Make changes according to the recommendations of each. This will contribute to the play's unity, coherence and emphasis.

Meanwhile, of course, you have had various of these versions typed, and copies have been sent to a number of producers—let's say a dozen, in round numbers. Wait six months, —no longer!—for replies, and at the end of that time write servile notes to each, asking what he thinks about The Dream-Girl of the Bar-X Rauch, and what the chances of its production might be. Out of the dozen, you will receive answers from three. The others will have "misplaced the manuscript, but Mr. Sclunitzky, who is at present out of town, will look into the matter when he returns". Mr. Sclunitzky apparently is overcome with permanent aphasia. Of the three who return the play, two will be happy to see it again when you have re-written it according to suggestions—one likes the dialogue and the characters, but thinks the plot very thin; the other admires the plot, but considers the characters, types, and the dialogue weak. The last of the little group makes no comment whatever.

After sundry repetitions of this process, a day dawns bright and fair when one of the friends (I am assuming you have some left by this time) to whom you exhibited a version, comes to you and, slapping you heartily upon the back, tells you that he—yes, he!—is going to produce F. He has several thousand dollars saved up, from many years of earnest participation in the cloak and suit business. One business is just the same as another. He can. borrow many thousands more. What the managerial end of the stage needs is a few new live wires. There's a fortune in a play if you happen to hit. And so forth. Of course, this'll of yours isn't cpiite right yet, but everybody knows that all plays are built tip during rehearsals.

You are introduced to your friend's pal, who knows the theatrical game in and out, because, look, lie's been an assistant stage manager for the Shuberts going on ten years. The two assure you that you arc not to give a thought to the financial end of the production. You're to devote all your spare time and energies to making what small changes may be necessary. The try-out will occur early in July.

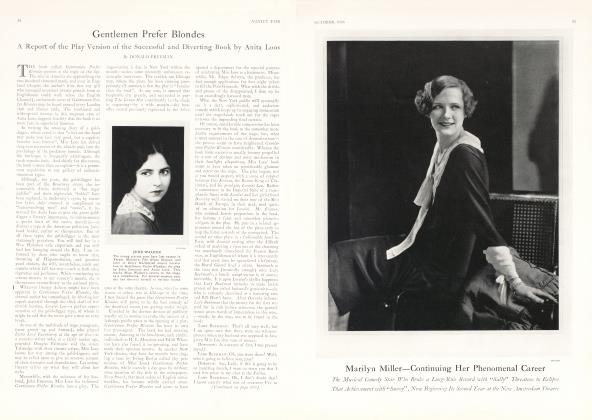

Now—how about the cast. Oh, yes—er—they almost forgot. You've heard of Elsie Delancey, haven't you? What, you haven't? Say, don't you ever go to the theater? Why, don't you remember the hit she made in Ashes of Orchids, that big Society drama which ran two years on Broadway just before we went into the War?

Oh, come, come, Miss Delancey married that Buffalo millionaire corset-manufacturer, and retired in 19 ! 6—always used to be photographed on the lawn of her immense estate, surrounded by her dogs and her kiddies—yes, sure. That's the one. You see, her husband went broke last year—corsets—well—so she wants to do a come-back. The critics have been clamouring for her return, your friend has met her, by a lucky accident; he showed her your play, which she likes immensely, and she's willing to work for practically nothing— think of the economy! (It occurs to you that you were just told not to concern yourself with the financial end, but there—production is production.) Also, think of her publicityvalue! Of course, Miss Delancey's forte is High Society Heroines in problem plays, and The Dream-Girl of Bar-X Ranch would be rather a new departure for her, and it's true that your description of Luella, the title-role, is "a slip of a girl, seventeen and dewy-eyed"—but a few changes will remedy that.

Continued on page 156

Continued from page 154

Well, well, the upshot of all this conversation is that you are confronted with Miss Delancey, and nothing you may find to say is listened to, so you just give in, and make an appointment to set about selecting the rest of the cast at Huntington Green's Agency, next Tuesday afternoon.

Only three weeks of interviewing and wrangling, and your cast is complete! True, your ingenue towers above you like the new American Radiator Building, but Miss Delancey is not exactly a pigmy herself, and who would be so idiotic—why, the mere thought of it is beyond human comprehension!—as to place in continual contrast with your star any ingenue who is petite, or obviously younger, or prettier (this last adjective you never use, anyhow, if you have any discretion), etc., etc. It's for the best interests of the play, Mr. McGonigle, and when you have had more experience, you will not be so stubborn.

Then, too, the gentleman cast for Old Pard Sawyer has never played anything but Cockney comics; TwoGun Hennessey is a stage-butler of many a season's standing—but don't you see, one of the plays in which he buttled was laid in San Francisco, so he is familiar with the Western atmosphere; Ma Wiggins will be in the hands of nineteen-year-old Genevieve Mjurphy, a little young, you think, but, don't be stupid, she handled all the First Old Ladies last year in the Majestic Stock Company, Peoria —now, look here, Mr. McGonigle, these matters will all adjust themselves. Just have a little patience.

With the first reading of the play to the company assembled in Finitny's Rehearsal Rooms—walk up seven flights, the elevator is unfortunately out of order—your fun really begins. Mr, Brougham, engaged as director, specializes in putting on bed-room farces—just the man for a tender little comedy of the Great Open Spaces. His one comment, made after a long and ominous whispered consultation with Miss Delancey, consists of the sentence, "Well—I'll do the

best I can." And rehearsals commence.

I shall not attempt to go into details of what really happens during these "rehearsals". I shall merely describe your share in them. You write. And by "write" I mean "rewrite".

Yes, having procured, at the risk of a permanent feud with your boss, a month's leave of absence, you arrive at the rehearsal rooms each morning well in advance of the company, and there you meet the director and Miss Delancey. The ensuing conversation becomes, as the days go on, stereotyped. There are always from ten to twenty-five pages which must be completely revised by evening, so that they can be "learned" by the various players overnight. You will note the quotation marks. Here are your experiences of any typical day.

Brougham demands more comedy in the dramatic scenes, more drama in the comedy scenes, that whole portion of the second act where Two-Gun Hennessey stole the five thousand dollars must be cut down to about ten lines, and a new climax manufactured, wherein Miss Delancey defends her virtue against the said Hennessey's depredations. And by the way, we've figured out what to do about Luella, the Dream-Girl. Miss Delancey simply will not play her as the "slip of a girl"; no, there is no emotion in the activities of a childish little chit. She insists that Luella be changed to a young New York widow, sophisticated and fascinating, who has come to these Western Plains for the purpose of finding her five-year-old son, who was kidnapped the year before, and has been traced to these environs. That will give Miss Delancey the opportunity to emote all over the stage when, shortly before the end of the third act, she opens her arms and into them rushes her "kiddykins". And what a final curtain, Mr. McGonigle! Little Jimmie clasped in a fond embrace, Luella kneeling, sobbing over him, Silent Bill standing, one hand fondly upon the mother's head, while over the Sierras glows the dawm of a new day—just a "smash", that's what it will be!

What price protests? Miss Delancey treats you to her whole box of tricks then and there—from outraged dignity through violent rage and Billingsgate to hysterics. You give in. No, it won't be necessary for you to watch Mr. Brougham's activities. Better get back to your room, and pound these changes off on the. typewriter.

You go. And you write. You never Avitness five minutes of any rehearsal. "Yours not to reason why," as Masefield puts it. You do what these experienced theatricians tell you —that's your job. They know their business.

Such is, as I have said, a typical rehearsal-day, so far as you are concerned. If it isn't one thing, it's

twenty or thirty others. You get three or four hours' fine sleep a night. You eat on the run. You lose all sense of proportion. You lose your memory. You have no longer any idea what the play is about. All you can think of is scenes —scenes and more scenes.

Continued on page 158

Continued from page 156

So it goes.

Then, suddenly, one roasting Sunday evening you find yourself standing in the entrance of a Certain Theatre, in Asbury Park. Ten minutes more, and you will be witnessing your dress-rehearsal. But what is this? You look again, more carefully, at the poster. It can't be true! You rush headlong to the stageentrance, and fight your way to Brougham.

"Why—oh, of course, Mr. McGonigle. Why, didn't Mr. Oomsgantz tell you? I suppose he was so busy trying to scare up the money for the Stamford guarantee. Yes, we knew you wouldn't mind. You see, The Dream-Girl of Bar-X Ranch is entirely too long a title. Yes, that's right. So's Your Old Man —pretty snappy, eh? Oh, you'll get used to that. It'll have a dozen new names before it hits Broadway. Now, you'll have to excuse me. The proper ty-m an—"

In a semi-coma, you drag yourself to what the theatre architect has jocularly called an orchestra seat. All the way down on the train, with a trunk in the baggage car for a desk, you have attacked your portable typewriter in a frantic attempt to create suspense for the finish of Act I. Your evening meal has consisted of a concrete sandwich, a cup of hot lye, and continual scribbling upon the backs of menus. Now, waiting for the curtain to rise, the comparatively restful gloom of the empty arena is temporarily too much for you. You doze, a ghastly doze.

But not for long. Your eyes snap open just as the curtain wheezes upward. At last! Your brain-child— alive and kicking!

But—what's the idea of the bed? Right in the middle of the ranchroom !

And—Miss Delancey, attired in the sheerest of negligees, yawning prettily, rising daintily from the billowy sheets, calling in dulcet tones for Ma Wiggins!

What is she saying? Her words are drowned by the whistling of a railroad engine, which has just come to a halt directly back of the theatre, and is occupied in calling to its mate. Miss Delancey is obviously used to contr»t+*»fi like this. As if frozen, she holds the pose she has taken, wordless, until the engine has ceased its awful amours. You have a flash of a childhood game, "Still-pond, no more moving." You recall hazily that somebody said everybody made allowances for the trains at Asbury.

But your head is definitely beginning to whirl, at first slowly, then with a gathering momentum. For Miss Delancey has begun speaking again, and the words are devastatingly clear.

"One of God's own glorious mornings! The air is like champagne!"

Why—why—that speech belongs in the third act! And Luella didn't say it—it was in Western dialect, and you had placed it in the mouth of Two-Gun Sam! "One o' God's own glorious mornin's, ma'am! I guess the folks back East 'd say it tasted like champagne!"—that was the way it began!

A suffocation is descending upon you. You fight for air. Then you hear a voice at your elbow. It is Brougham, who is watching the stage while he talks.

"I suppose you wonder about this opening, Mr. McGonigle. It's very simple. You see, Miss Delancey thinks that speech is a wow, so I took it over from where you had it, and gave it to her. Oh, that's what we call 'switching'. We always do that. It's what we call 'good theatre'."

You try to pry your mouth open for a reply. But a new shock wallops your failing senses. Revolver-shots off-stage—Luella rushes to Ma Wiggins—there is a fearful knocking at the door—

"We switched that, too. You'll see. It's a lot better here than in the third act—why, Mr. McGonigle —hey, what's the matter?"

But you never answer. With a shriek you have half-risen from your seat, and have fallen back, unconscious. Sweet oblivion.

It is a month later when you leave the hospital. You lean on the shoulder of Oomsgantz.

You have convalesced rapidly in the last week. True, you were delirious for twelve days—but, strangely enough, at the very moment So's Your Old Man, an American comedy by Wilfred McGonigle, rang down its final curtain amid the complete silence of seventy onlookers in Hartford, you opened your eyes, and said to the nurse, "Where am I?"

Oomsgantz is bearing his woes bravely. He has given notes for the other two thousand, and he says you were a hell of a good sport for waiving your advance royalty. You'll get it, some day, honest to Pete.

Yeh—the play is in the storehouse. No—he's afraid it won't ever come out.

Think you're strong enough to look at some of the notices? You lean back in the taxi, and shakily glance through the clippings.

Asbury Park: "Even the most expert efforts of Elsie Delancey failed to rescue So's Your Old Man."

Long Branch: "An inane potpourri of bunk . . . despite a splendid cast and that able director, Brougham. . . ."

Stamford: So's Your Old Man opened at the Stamford Theatre last night. Why? . .

Hartford: ". . . The author must have recently escaped from Matteawan. A perfect cast, well directed."

Lovingly you caress the envelope in your pocket. Ah, those beautiful words from your boss, "We have held your job open for you. Come back as soon as you feel able."

"Well, better luck next time—for both of us," Oomsgantz is saying.

Next time!

You have acquired water on the brain, anthrax, and housemaid's knee.

But—Playwright's Itch? Cured!

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now