Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowPoor Carlotta

A Program Note for a Chronicle Play Currently at the Guild Theatre

ALEXANDER WOOLLCOTT

JUST fifty years after the heartsick Carlotta set sail from Mexico in one last hysterical attempt to drum up Europe's waning interest in the grotesque enterprise which had made her for a little time the Empress of the difficult and singularly unappreciative land below the Rio Grande, the curtains rose in New York on a chronicle play which sought to dramatize that enterprise. For it was in the chill dusk of a day late in 1866 in a curtained carriage summoned hastily to the Vatican where, in her last despairing interview with the Pope, her reeling reason had given way utterly, that poor Carlotta rolled along the streets of Rome and out of history—out of history into the twilight of the Sunday newspapers and an. occasional paragraph in those sedate despatches which still issue from the fast disappearing kind of correspondent who writes out his pieces for the American papers in long hand and sends them here by mail.

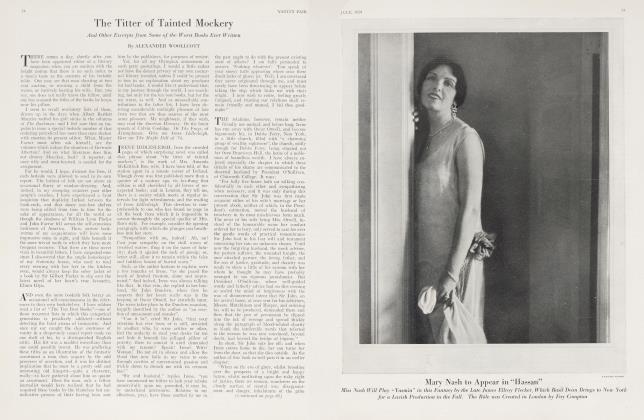

To our own Clare Eames, busy in the early weeks of this autumn with the wigs and pretty bonnets and billowing crinolines for her role as the Empress Charlotte, it must have seemed that the trusty Mexicans themselves were seeing to it that the very front pages up North should play a kind of ominous overture to this Juarez and Maximilian which the Theatre Guild has selected as the first play for its new season. And to Miss Eames, as she learned her lines and practised the fine, peacock sweep of Carlotta's walk, it must also have seemed like a faintly monstrous touch in an Einstein phantasmagoria that, even as the rehearsals advanced, over in Belgium behind the walls of a chateau where the clocks stopped half a century ago, Carlotta herself, the tottering ghost of a dead day, was still living on.

IT* OR, of course, it was to the asylum of Belgium that they took her at last. After all, the Princess Marie Charlotte Amelie Auguste Victoirc was a Coburg, born and bred. Old Leopold was her father and it was from Brussels that she had gone to marry the personable Maximilian, adrift then among the embarrassed chancelleries of Europe as the younger brother of Franz Joseph of Austria. It was a love match then and always between these two and every one was so pleased including, of course, her cousin Victoria, who celebrated the wedding back home by ordering wine for her servants and extra grog for her sailors and indulging herself in a very rash of italics and underscorings for that day's batch of letters.

Maximilian was a vague, kindly giant, devoted to Charlotte and to botany and to the personal care of the loveliest set of golden whiskers then extant in envious Europe. All dressed up, he was, and no one to rule. There have been few more absurd ventures in recorded time than that pretentious but fundamentally half-hearted expedition in which this affable young man found himself sailing across the world to become emperor of remote and uncordial Mexico. There is something more than half illusory about even the most insistent and republican summons to rule. But surely there never was a fainter whisper in all history than that which called the mild Maximilian from the scholarly tranquility of Miramar to the uneasy throne of Mexico.

The original expedition, made possible at all by the circumstance that Mr. Lincoln had a war on at the time in his own country, had been inspired by the repudiation of foreign debts which so endeared the bleak and alarming Juarez to his following among the mere natives. It was an expedition sanctioned and even blessed, for Juarez had promulgated that very anti-clerical decree which President Callcs has more recently been trying to enforce, with results, in sheer newspaper space, so gratifying to the press agent of the Theatre Guild.

AN old grafter in Paris was involved in the invisible intrigue which sent a swarm of French Zouaves to die under a Mexican sun. The Commune got him later. Then one of the batards whom the first Napoleon left behind him was financially interested in any debt-collecting the French government could undertake. And Napoleon III was heavily responsible. Guedalla, in the brilliant Mexican chapters of his incomparable Second Empire, makes this crisp observation:

"The Emperor had once stayed at the Washington Hotel, Broadway, and he suffered for thirty years from the hallucination that he understood America."

Into the motley skein which noosed the naïve Maximilian for the affair were woven many threads beside the brightly coloured single strand on which Guedalla pounces when he more than half implies it was the whiskers which made his selection inevitable. If you poke about a bit you may come to the conclusion that the choice of him rather than another had its origin in a squabble over a complimentary box at the opera in Paris years before. But, of course, the great factor was Charlotte. She wanted to be an Empress.

The Mexican emigres in Paris cheered them on their way, much as you may even now hear fearful threats against Moscow across the tinkling wine glasses any night at the Chateau Madrid. Indeed, the whole expedition had about the validity and the chance of success which Wrangel's army enjoyed when it took a peck at vast, oblivious Russia.

In time the hollow cheering died down. Then the money ran out and at last the French troops were recalled. Maximilian was left alone in Mexico to face a foeman he had never seen— the phantom Juarez who had but to vanish in a waggon train towards the inaccessible North and wait until time and the Mexican sun disposed of that preposterous and impertinent invasion. Finally he was in the position to order Maximilian's death and the order was signed.

YET, far from grappling with Juarez, Maximilian had never even laid eyes upon him. That baffling element in the incongruous duel has been most cunningly translated in terms of the stage by this Franz Werfel, the young playwright from Prague who followed his Goat Song with this Juarez and Maximilian. For in this play, Juarez does not appear at all. You in the audience see him no more clearly than poor, befuddled Maximilian did. In the dramatic version of his great triumph, he remains a shadow, a threat, a presence in the wings and towers the more, of course, on that account.

The sound of the volley which pitched Maximilian into the dust at Querétaro never reached Carlotta's ears. The woe she knew was her portion, when she arrived in Paris and found no one to meet her, had unseated her reason in time to spare her that final blow. Indeed, in the tidings of her which, from time to time, have seeped through the high walls of her kindly shelter, she has ever been pictured as thinking herself still Empress of Mexico and thinking of Maximilian, who has now been dust for nearly half a century, as the handsome fellow who was in the next room, probably— and might come striding through the curtains any minute.

The world has always been fascinated by the figure of the immured Carlotta, a fortress invested, a character from some other play somehow preposterously left on the stage long after the curtain had risen on a new one. The world has clasped to its romantic heart the tales of the pitiful, pitying mummery of court life, the attendants backing out of the room, the telltale mirrors removed from the chateau walls, the same old birthday gifts trotted out year after year—this from Victoria, that from Franz Joseph and another from dear Leopold—all the tender conspiracy to spare the mad Empress.

One by one, the others of her day vanished from the scene. Napoleon, himself, riding ingloriously out of Sedan, then the great Queen across the Channel, then Franz Joseph, then, at last, even Eugenic, who seemed, towards the end, so incredible an anachronism. But Carlotta still lived on. The world war rolled its tide to her very gates but even that did not disturb her merciful oblivion, for the German commander saw the Hapsburg crest over her portals and his orders bade the soldiers walk softly past the house where Carlotta dwelt.

(Continued on page 110)

(Continued from page 63)

Now they have brought her youth to life again for a few hours on a New York stage. One wonders if she knows that. It is possible. For in the summer the cables said Carlotta had had a lucid interval. And if, she could see that play, one wonders, too, if the character as played by Clare Fames would seem to her any more remote and unbelievable than now, across the vista of the years, does the ambitious, loving, insatiate Charlotte, who sailed across the sea so long, so long ago, to be the Empress of Mexico.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now