Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Light Fantastic Show

The Disappearance From the American Stage of the Sheerly Imaginative Play

GILBERT W. GABRIEL

THE heyday of the Hippodrome was the ideal of fantasy on the American stage. That great grey lion couchant of Sixth Avenue, whose electric eyes waggle so valiantly above the "El" tracks nightly, used, in days before the net of vaudeville ensnared it, to lend its insides to tremendous spectacles of song and ballet, pet menageries, gymnastics, ice-skating, water-diving, panoramas as exotic as they were enormous. In an atmosphere damp with the spray of unexpected fountains and faintly tinctured with the presence of huge, complacent elephants, we breathed at once the spices of the Orient, the nectareal brine of Neptune's Court, the rare and painty air of some mythical woodland conclave where all the birds of brightest plumage took on human legs and practised amazingly gregarious gyrations, or where the hundred most prized gems from jewelers' lore, come suddenly to life, flashed fires from their leaping sequins. That was fantasy, all of it: fantasy with a thousand facets and resources. Like unto the Hippodrome we shall never be so lavishly fantastic again. But like unto the Hippodrome all our attempts at fantasy must evidently try to be for a century hereafter.

Carry the origins back further, if you insist, to the circus. Possibly it was Phineas T. Barnum who first expounded the meaning of fantasy in America: the blare, the dazzle, the gasp, the three-ring wonder, the glut of oddities seen but still unbelieved, to the accompaniment of a ra-ta-plan of crackling peanuts. But the circus is romantic only to the extent of your powers to generate romance of your own accord. Its marvels are matters of fact, not of imagination. Its appeal is muscular, its gaiety animal throughout. It permits you not a single moment of that gentle pensiveness, that instant settling of the feather of fun on the tip of the nose of sorrow, which true fantasy requires. It was only when the Hippodrome could turn the circus slightly, so slightly, self-conscious, that things were fecund for fantasy.

But then, fantasy is probably the thinnest of all strings to pluck in any etude of American drama. Its vibrations must be almost wholly negative. The theme is not of our fantasies, but of our lack of them. Not a single genuinely fantastic play has ever been worth its watts in footlights on our stage. Few as have been attempted, fewer justified the attempt. You must fling your latitudes wide if you wish to recollect any fantasies by American playwrights at all.

BECAUSE a benign old ghost lends his influential presence to the scenes of Belasco's The Return of Peter Grimm, for instance, you may call even so unfantastic a play a fantasy. If so, in spite of this, that and Belasco, it remains perhaps the best knit and most interesting one any American has yet constructed: simple, moving, semi-real, gently eerie, lacking only in that sensitive capriciousness, that whim for whim's own sake, which is come to be the blade-mark of all proper Anglican fantasy.

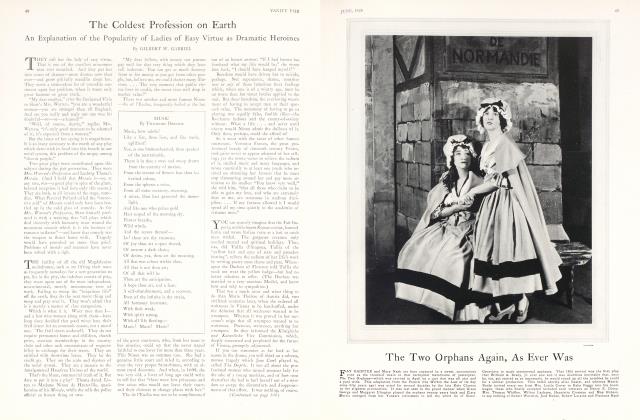

Talk of fantasy to a Londoner (or a New Yorker, for that matter) and you arc inevitably talking of Barrie. It is gone out of date to recollect even A Midsummer-Night's Dream when Dear Brutus or A Kiss for Cinderella is so much closer to modern memory. A cupful of Perrault, a pinch of Phil May, two or three grains of sweetened Rochefoucauld, stirred into a sort of High Episcopal Hansel und Gretel— and, sure enough, a Barrie fantasy is ready for the public oven. No complaint against such nice ingredients. But they have become the items of a standard recipe; and fantasy, of all forms, must suffer most from standardization. To the credit of those two or three Americans who have tried to twirl the light fantastic show, they have done their spryest to break through Barrie's fairy ring of wistfulncss.

Many fond hurrahs were exhaled last season in praise of Marc Connelly's The Wisdom Tooth. Quite all of them congratulated the somewhat distracted author on the kinship of his pen to Barrie's. Fantasy, Barrie . . . an irremediable conjunction of terms. But there was five times more of James Whitcomb Riley in The Wisdom Tooth than of Barrie. It was American in its sentiments, in its satire. For style it wore shirt-sleeve garters made nowhere but in the U. S. A. And, speaking of satire, it prickled with those comical barbs which we seem to feel necessary to the fulfillment of fantasy over here. Three-quarters of such plays of ours have used the fantastic only as a means to travesty and gibe. Mr. Connelly was more lenient about it in The Wisdom Tooth than he and George Kaufman were in that Beggar on Horseback which they so successfully dc-Tcutonized a few years ago—but the parentage was apparent. Barrie was not even a godfather of the affair.

The only wholly, steadfastly fantastic piece of American playwriting in recent years was Sidney Howard's and Edward Sheldon's Bewitched. A dream play, a castle as mysterious as Otranto, a hero tumbled from the clouds, a wicked old magician, a maiden elusive as the shimmer of leaves in the old French forest where she wandered . . . here was the stuff of pure, untroubled fable, distillation of honeyhued fancy. Bewitched failed. Of all moods to which the stage may consecrate itself, fantasy is the most difficult to enliven, humanize, sustain. It needs more nimbleness to keep a toy balloon off the ground for three hours at a stretch than it does to uphold a millstone.

But Bewitched failed more conclusively because of its audiences than of its own fault. It was elaborately wasted on a directory of hearers who can no longer hear of fairies without smirking, and whose turn for legendry is done up in chuckles at the warts on the knuckles of the signers of the Declaration of Independence.

As with great playwrights, so it is with huge populations: only after the pain, the hardbegotten wisdom of long years—the precious and ultimate wisdom to put reality in its place —can reverie be honorable, caprice a boon, fantasy prosperous. For fantasy may begin as the mothering comfort of childhood, but it is more often the petted elf of dignified and saddened dotage, the last and secretly favourite descendant of one whose knee is not yet too withered for dandling, but whose eyes, factsick, arc already on God's top-story windowpanes.

WE have shot up—quickly, boisterously— past our age of innocence. We are still far in thought and feeling from senescence's hearth-chair. We neither believe nor disbelieve enough to be makers and followers of fantasy. Neither sufficiently naive nor sufficiently decadent, we can only resent those liberties which the fantastic takes, can count exquisiteness of idea for exquisiteness's own sake naught but a silly and presumptuous trespass. We are as apt to accept a fantasy without a blast of utilitarian satire in it as we are to elect a congressman without a platform.

Mr. John Howard Lawson, who described his exciting Processional as a "jazz symphony", would probably ram a beam into any eye which saw this play of his in the light of a fantasy. Fantasy he certainly did not intend. Nightmare, perchance, truths tipsy, the hot rampage of corn-whiskey scummed with coal-dust, and none of your sweet, sparkling Rhenish wines. Yet fantasy is in the smack of it, for all that. Hoarse, coarse, painfully plain and forthright fantasy, pitched to a snarl instead of to a coo, perfumed with sweat instead of with patchouli, daubed with such dark slobber and swift, sulphuric highlights as turn the fun of it vengeful, the agony of it purposely vulgar . . . fantasia none the less it is, fantasia for trombone and bassdrum, not for harpsichord.

(Continued on page 106)

(Continued from page 83)

Disciples are already rushing up Mr. Lawson's alley. John Dos Passos's The Moon Is a Gong was even more admittedly fantasy, and no less frenzied. The same clew of savage parable, the same social buffooneries and ecstatic vituperations, the same rabies of taunt and beauty in and out of modern highways. Above all, the same sense of latterday Harlequins self-crucified on the steel girders of our newest sky-scrapers. This way goes fantasy in America—but how far?

Meanwhile, we weary almost immediately of the tender musings of Maeterlinck's The Blue Bird. Even Molnar's all too sophisticated faculty of turning gutter-pups and bawdy-house keepers into bright angels by the mudbath process—we treat it as an irrelevant stranger in the midst of our everyday drama. The mood of fable in The Glass Slipper went all for nothing—or for worse. Because humanity on fancy's terms is not for us. That is a heritage we decline truculently, scarcely covet.

And, in a world that is too much with us, what heritage could be higher? The laughter in a frisky terrier's bark is proof enough that dogs, too, have their idea of comedy. Tragedy cannot be wholly beyond the ken of bees around a shattered hive. Ask some gaily tossing butterfly the meaning of realism, and he will not hesitate to plunge his antennae into unmentionable filth. But, to know the commonplaces of comedy and twist them into enchantment, the grit of tragedy and turn it whimsical, the bondage of reality and the way of escape from it into an empyrean where truth is measured by no such commercial rules as time and space and plausibility . . . this seems to be the holy privilege, the excellent and unique talent of that peculiarly pink and hairless cousin of the primates, man.

But as for man in America, he will have none of it. He will not even have the Hippodrome.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now