Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowWhat Does a Murderer Look Like?

Confounding the Popular Theory That There Is Such a Thing as a "Criminal Type"

EDMUND PEARSON

IN a reformatory which I once visited the warden made two remarks about the theory of the "criminal type."

"Lombroso," said the warden, "believes that there are certain physical signs of the criminal; and that by observing the facial angle, or measuring the cranium, you can distinguish the man who is predisposed to crime."

He paused, and then continued without the flicker of a smile:

"I will guarantee that every facial characteristic, every measurement of the head which you find among the men in this institution, can be duplicated in the present Legislature of this State."

Disregarding the flippant impulse to suggest that this merely confirms the general impression of Legislatures, it should be said that experiment has proved that the warden's assertion was justified. Take any group of six hundred men, give them the pallor, the cropped head, and the prison clothes, and place them beside six hundred convicts. In both groups you would find a few "evillooking" men; a few noble-looking ones; some, intelligent in appearance, some sly, and some stupid. About the only great difference would be that among the convicts there would probably be a larger percentage of the stupid type.

THIS is a layman's method. A thoroughly scientific test of the criminal type has been made in English prisons. It left Lombroso's original theory almost completely discredited.

Convicts include few of the "perfect heasts" which one class of sentimentalists imagine; still more is it hard to find among them the capital fellows, who have been cruelly misunderstood and unjustly confined, which another class of sentimentalists seem to think make up the inmates of a prison.

The murderer is a superior type of criminal, according to some of the authorities.

"I have known many murderers whose sentences were commuted," writes Sir Basil Thomson. "I can remember only one—Steinie Morrison—whom I would not trust not to commit a second murder. The rest were always a good influence in the prison and qualified themselves for positions of trust."

Doubtless this view was shared by the Governor of an American State who recently took two murderers from the State Prison with him on a fishing and hunting trip,—as boatmen and gun-bearers. But I think I read that people in Canada, where the Governor's party travelled, were not wholly pleased. That Governor, I should expect to find, was the kind of person who, as a boy, left loaded revolvers lying about in the house, and considered it rather amusing to do so.

A man who commits murder, says one brand of dogmatist, rarely commits any other crime. This is his only offense. The statement sounds rather well, until one remembers Jesse James, Gerald Chapman, and the great horde of burglars and others who have included murder in their programmes.

Of course, say the superficial thinkers, all murderers are insane. If not raving lunatics, they are insane at the moment of the crime, and that is why it is useless to punish them. This assertion represents thought at its lowest ebb. I used to believe that it had at least a noble motive behind it; the desire to make a merciful excuse for sin. But I am coming to agree with William Bolitho that it represents mercy not so often as cowardice; not so much the desire to excuse others as to defend one's self. These folk who have committed murder are not insane; they are "nastily like ourselves", and their dreadful deed only represents something which, under certain circumstances, we might have done. The plea of insanity may be raised to save a guilty man, or it may be only a cry of horror to prove that there is a wide difference between the wicked murderers and ourselves,— virtuous folk that we are!

There are few subjects upon which people are so ready to dogmatize as upon the signs of innocence or of guilt. And few upon which they are so willing to jump to general conclusions from one instance. During the strange manifestations of mob psychology which appeared in the Sacco-Vanzetti agitation, more than one person remarked upon the noble utterances of the condemned men, and argued innocence therefrom. One of the intellectual weeklies was much impressed by their dying speeches, and asked solemnly if these were tin' words of guilty men.

WELL, Carlyle Harris died with simple courage; a neatly-turned phrase upon his lips. He quietly asserted his perfect innocence. Dr. Pritchard, who atrociously poisoned his wife and mother-in-law and tried to lay the blame for the murders upon his poor little dupe of a house-maid, appeared upon the scaffold, with the bearing of a sainted martyr. He even took time impressively to thank one of the clergymen for appearing in full canonicals. And about the time of the Sacco-Vanzetti execution, there was published in the papers an interview with a newspaper reporter, Charles A. Leigh, who has witnessed eighty executions at the New Jersey State Prison. Every one of the eighty murderers protested his innocence to the last.

But it is upon looks, upon facial characteristics, that your ready-made criminologist, your reader-of-character-at-a-glance, is most willing to reply.

"Why, he doesn't look like a murderer!" say these folk. And they reach for a pen to sign a petition to the governor.

"What, that innocent-looking boy?" "That sweet-faced woman?" "That poor, honest working-man with such appealing eyes?" "Never in the world!"

Their sympathies are enlisted in the prisoner's behalf, and presently they join in calling all the authorities by the harshest of names. Governors, judges, presidents of universities,—all are tyrants and hangmen. To the humanitarians who agitate to procure the release of condemned murderers the world is a black place, full of scheming villains. Figures of pure radiance seem to exist only in the cells of the condemned.

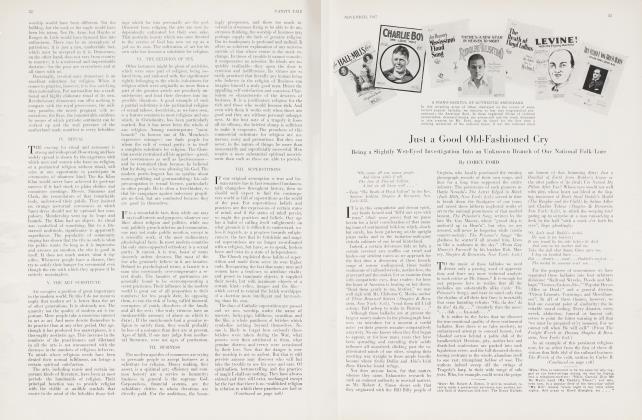

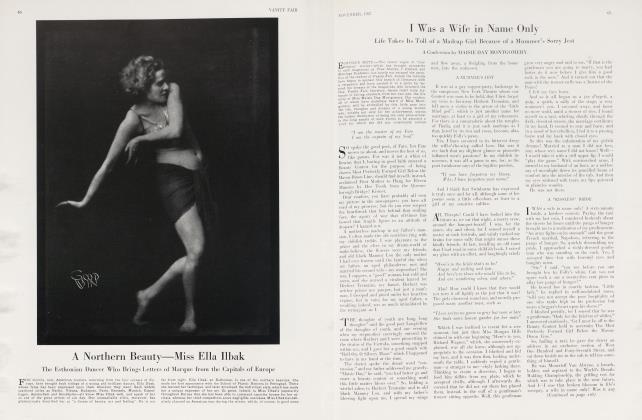

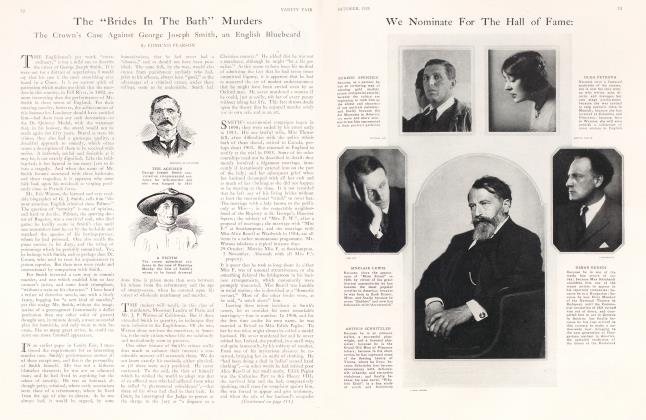

The seven persons whose portraits appear on page 8^ (opposite) were not from the "criminal classes." All except one -Louis Wagner—were apparently good middleor upper middle-class folk. Major Armstrong was M. A. of Cambridge University, and a solicitor, living in comfort, and enjoying some social position in a small English, or rather Welsh, town. The Rev. Mr. Richeson had been graduated from a theological seminary, and was the pastor of a church in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Dr. Lamson was an English physician who had occasionally visited in Saratoga and other places in New York. Constance Kent was a member of a notably "respectable" and religious family, although there was a record of maternal insanity in her case. She herself, however was adjudged sane, and the death sentence was commuted because of her youth.

RONALD TRUE passed as an officer and a gentleman, in both the British and American aviation services during the War. He murdered a prostitute for no apparent reason except to rob her of £8. He was found legally insane; unless he has died, He is still confined in an asylum. The commutation of his sentence was much criticized, and there were those who believed that he fooled the doctors and the law to the end. Mrs. Thompson seemed to be a perfectly normal person; she suffered the extreme penalty of the law because of the extraordinary letters to her lover, in which she represented herself as trying to poison her husband. When that lover stabbed the husband to death, in her presence, she was held to be a party to the crime. Louis Wagner was a man in most humble circumstances; an ill-educated fisherman; poor, but no better and apparently no worse than the average man living among sailors and fishermen on the waterfront of seaport towns. His photograph was taken during his long confinement in prison prior to his execution; I suspect that the photographer, or some kindly jailor lent the clothes to give him the tidy and almost clerical appearance.

I should He surprised if some of those who see these pictures do not fancy that they detect criminal or murderous characteristics in all of the faces. I should be surprised if these same persons, if they had been told in the printed captions, that these were not murderers, but the board of directors of some charitable and philanthropic society, did not remark that these were very kindly and pleasant persons. For myself, I can see murder in none of the faces. Yet six of these people committed cruel and atrocious crimes; the victims of Major Armstrong, Dr. Lamson and Mr. Richeson died in agony, after hours of suffering. The victims were a wife; a crippled brother-in-law; and a betrayed and deceived sweetheart,—a girl of nineteen.

Continued on page 136

Continued from page 83

Constance Kent and Mr. Richeson both confessed their crimes; the others all protested their innocence, although there is no doubt about their guilt, with the barely possible exception of .Mrs. Thompson. Louis Wagner rowed out from Portsmouth, N. H., to the Isle of Shoals, on a winter's night, surprised three sleeping women, whom he knew to he there alone, and murdered two of them with an axe. The other, who fled in the snow, clad in her nightdress, He hunted hut failed to find. All of them had been his kindly friends. He hoped to find six hundred dollars in their house; actually he got about sixteen. In jail he became sanctimonious, and by means of his innocent appearance, his professions of religious faith, and by blaming the murder upon the woman who escaped, managed to fool a fewpeople, and found a legend of his own innocence,—a legend which lingers today in that type of mind which always prefers rumor and gossip to easily ascertainable fact. During the last day of the Sacco-Vanzetti appeals, the Governor of Massachusetts was made to listen to the ancient rigmarole of Wagner's innocence—a slander on a dead woman and an attempt to whitewash a murderer—advanced as a reason why Governor Fuller should commute the sentence on the two Italians then awaiting execution. This was a sterling example of sentimentalism run riot,—in this age which so vociferously expresses its contempt for the sentimentalism of the Victorians.

The stories of Mr. Richeson and Miss Kent are rather widely known. To Mr. Richeson, the presence on earth of Miss Avis Linnell was an embarrassment. She was pregnant, and He desired to marry another and a wealthier lady. He gave Miss Linnell cyanide of potassium and she died in torment. He confessed and was executed. Constance Kent, a spirited little girl of the Victorian era, disliked her step-mother. At the age of thirteen, and wearing boy's clothes, she ran away from home. This was not effective, and when she was sixteen she protested further by taking her halfbrother (aged four) out of the house one night, and cutting his throat.

Major Armstrong must be regarded with mixed emotions. It was for the murder of Mrs. Armstrong that he suffered at the hands of the hangman, but it may he admitted that his wife was an exasperating person. She permitted the Major no wine or alcoholic drink, even refusing for him if he were offered either at a friend's table. Occasionally she would relax this severity and say: "I think you may have a glass of port, Herbert; it will do your cold good." He had to hide his cigar or pipe when she came into view. And, once at a tennis party, she broke into the middle of a set, and commanded him to lay down his racquet, and come home.

"Six o'clock, Herbert; how can you expect punctuality in the servants if the master is late at his meals?"

After this we look around to discover for what reason the English lawhanged Major Armstrong. We find it in that he forever pestered a fellowsolicitor to come to afternoon tea. He had entertained this brother solicitor on one occasion—after Mrs. Armstrong had been removed by the arsenic method—and given him a hot, buttered scone. The Major selected the scone and handed it to his guest, with the remark, "Please excuse fingers." The guest ate it, and after arriving home, was violently ill. An analysis found that the scone had been prepared with something more than butter. He declined all further invitations to tea at the Major's house and office, although the invitations were frequent and pressing. Finally, after being rung up daily and urged to come, he w'as forced into taking tea in his own office and bolting it early in the afternoon, so as to have a legitimate excuse for disappointing the Major. All this set him thinking and it set in train the events that led to the Major's downfall.

There were many neat little packets of arsenic in Major Armstrong's possession. He used them to kill dandelions in the lawn. I can see that in his face; he would be an implacable foe of dandelions. He made up twenty of these packets; each containing a fatal dose for a dandelion, and this was also a fatal dose for a human being. He used, he said, nineteen of them on the dandelions, one packet was found in his w-aistcoat pocket,— all ready when he should meet the next dandelion. Mr. Justice Darling, the humourist of the English Bench, examined him sedulously about these flowers; just how many there were, where they were, and w-hat happened to each one. If his were a Sherlock Holmes story, I think the Armstrong case would be called The Adventure of the Twentieth Dandelion.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now