Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

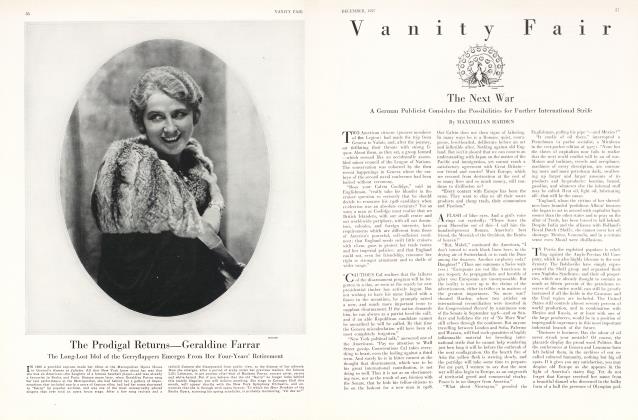

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowJames Cruze

Hollywood's Severest Critic Estimates the Famous Director of "The Covered Wagon"

JIM TULLY

HE is heavily muscled, broad-shouldered, and leonine. As simple as a child, he is as deep as the riddle of life. His real name is Jens Cruze Bosen. He is the son of a Mormon Danish immigrant—a fanatic who settled in Utah as a follower of Brigham Young.

At fourteen, young Bosen ran away from home and changed his name to Cruze. He became in turn, a hobo and later a roustabout on a whaling vessel which plied Alaskan waters for two years. His next occupation was that of a waiter on a passenger steamer bound for Japan. When asked about that country years later, he replied, "All I remember is Crib 18."

At eighteen years of age he entered a school of drama and remained two weeks. He would have no more of the academic.

Self-conscious, even to the verge of painful shyness at times, he has no sentimentality and no illusions about life. In speaking of movie directors he once said to me, "None of us are great."

His black eyes are quick and somnolent by turns. He is all fire at times and completely drowsy at others.

He has the one track imagination and intuitive sense of balance in exaggeration which makes of him a great verbal teller of picaresque tales.

He is forty-four years old.

HE has enemies .... a few who are temporarily powerful—but who are silhouettes of men in comparison with the magnificent ruffian who is, at seven thousand dollars a week, the highest salaried director in the world.

The treatment accorded James Cruze is, to me, a perfect example of the lack of foresight and knowledge of human nature exhibited by producers. He has directed over fifty pictures, only two of which have not been commercial successes. They have made a mannequin of a master.

It was only by accident that he was given The Covered Wagon to direct. He was the one man fitted by nature and background to direct this picture. This, of course, the producers did not know, as he had only been nine years in pictures, and had directed only forty-odd films.

He had been half starved as a lad on the Utah desert. His father was a giant, weighing three hundred pounds, with the physical strength of a Perclieron stallion and the limited mentality of a Harvard graduate turned scenario writer.

His mother was of the same breed.

As illiterate as Millet's peasants, his parents were nevertheless strong plants—untouched by the fungus of pseudo-American civilization.

Their son heard tales of the pioneers from babyhood. From somewhere out of the centuries he has inherited a strong and powerful brain.

With less than two years of schooling, and that in a pine shack in the desert, he has somehow managed to become a great student of Shakespeare. The poetry of Shakespeare does not impress him. The Mighty Master's ability to pack a world of meaning in a line is the quality which appeals to him. Looking over Cruze's career one discovers but one weak point in it. He became an actor.

He traveled by stage and narrow gauge railway all the cheap theatrical circuits of the West. He remained three years with one show. He played Uncle Tom's Cabin in a small hotel dining room; he played Hamlet under a tent; Othello in a sheep-herder's home.

When business was dull on the stage, he would work as a waiter. After an ineffectual existence in New York he became the star of one of the best known serials ever made— The Million Dollar Mystery. He had acquired a slight reputation in the playing of Indian roles in western states, and tried to repeat his success in the East.

He returned to California after a five years' absence and stormed the gates of Hollywood. He was given work as an extra player at five dollars per day. Ignored more or less for many months, few realized that he was to increase his salary by nine hundred and ninetyfive dollars a day within eight years.

With such a background, and after he had directed more than forty films for Famous Players-Lasky, there was no man in the organization with a keen enough knowledge of personality immediately to select James Cruze to direct The Covered Wagon.

After every director on the lot had expressed disapproval of handling the film it was given to the Danish-American. Cruze had been a trial horse who'had never failed.

When the picture had been given to Cruze, another fortunate thing happened. It was discovered that the film could not be taken on a small background, so the company sent him to Utah with his crew of several hundred players and floating gentry of humanity.

As the distance was too far for company officials to travel, they were forcecf to allow the director complete individual expression.

Away from studio politics and the gentlemen from Judea who control them, Cruze found himself for the first and only time in his directorial life. He returned from the desert after many months with one of the greatest pictures ever made—artistically and commercially.

Frisco, the Broadway wit, said of it later"It's all right if you like wagons." The remark was typical of Broadway. But even the morons knew better. It was one of the few pictures made in the world in which there was genuine emotion. In it the desert wanderer lived over again his agonized boyhood.

The men who had guessed millions out of films had made another excellent guess.

AS a leading Hollywood citizen, Cruze delights in saying that he does not read. "I only read stuff that will make a picture," he often says. It is the homage that a halfBarbarian pays to culture. As a matter of fact he has a deep knowledge and understanding of such diversified writers as Mark Twain, Krafft-Ebing and Schopenhauer.

I once arranged a meeting between Cruze and H. L. Mencken. Feeling that Cruze might be shy in the presence of so brilliant a man, I had warned Mencken and that kindly gentleman was ready to bridge any awkward situation.

Cruze met the sage of Baltimore at the door. He wore a large cowboy sombrero, a scarlet coat with brass buttons, and an expansive smile on his face. He greeted Mencken with:

"So that's you—well, I never read a damn thing you ever wrote.'"

And Mencken, holding out his hand, replied:

"Well, I never saw one of your damn pictures—that makes us both Elks." They talked not of academies or books but of life and became friends.

Cruze's mind is greatly like Mencken's in its restless feverish quality. The latter, a trained sharpshooter of the intellect, has nevertheless the same gusto for life as the former.

Like many primitive men, he knows without knowing why he knows. He drinks of the sap of life without looking for the roots.

In primitive force, in natural leadership of men, in direct, even brutal honesty, Cruze stands alone among Hollywood directors. In many respects he is the greatest man the film industry has produced. In spite of every handicap placed about him by the second lieutenants of finance, he has managed to make one great picture in The Covered Wagon and one picture which many discriminating observers have thought was among the finest of its kind, One Glorious Day. Cruze wrote the latter story himself. It was fanciful and different. Will Rogers was the star.

(Continued on page 114)

(Continued from page 82)

Cruze also directed the ConnellyKaufman play A Beggar on Horseback. There is no middle ground of opinion on this picture. Marc Connelly considers it a had piece of work. Cruze considers it better than the play. It was one of the two financial failures he has made.

Cruze is the master of broad and obvious comedy. The subtleties of life elude him. In literature he more often understands the Dreisers and not the Cabells of the world. And yet for years he has been interested in directing Twain's Mysterious Stranger; Will Rogers as Pudd'nhead Wilson; and Roscoe Arhuckle as the rollicking Falstaff. Studio officials have used all the blandishments of financial cajolery to keep him from doing the fantastic R. U. R.

The greatest defect in Cruze's character—next to his having been an actor—is—he calls Jesse L. Lasky, Mister. It is the key to the man. The obsequious waiter all over again— mightier than the accident of destiny he waits upon—but still obsequious.

The cost of each film is charged against the director in the final reckoning. Cruze is too aware of this. He is too often the young hobo burned deep by the branding iron of necessity. He is fearful of letting slip his thousand dollars a day.

There is in him the hard fibre of the man who succeeds in earning enormous sums for a corporation. It is only now and then that an inner urge hurts him. What is left of this tiny acorn in the man may yet make him the one oak among directors.

His mind would have been of the first order if it had not been commercially trained to pattern after other minds. His memory is astonishing. Whenever he has a flash of originality —which he often has—he remembers his thousand dollars a day.

Fully capable of inventing new forms and expressions for the screen —he does not wish to be a pioneer like his father.

He receives three hundred and sixtyfive thousand dollars a year by appealing to the lowest common denominator of mankind. "You can't buy Rolls Royces with art," he says.

If he were not forced to spend his time and waste his talent in hitting the moronic bull's-eye he would be the first really great director.

With a powerful faculty for observation, he too often turns life into a series of remembered "gags". A semibarbarian—a hedonistic mastodon in his capacity for the enjoyment of life, unmoral, and anti-social save in his own mansion, he is the despair and the delight of one who would try to analyze him.

He seldom removes his cap. Men are not encouraged to give their seats to ladies in his home. "If she's a lady she can find a seat for herself."

But down deep in the man is a profound love of beauty. He stood in his magnificent bedroom, which his wife, Betty Compson, planned for him, and said with a softer voice than usual: "This is the first beautiful room I've ever had." Cruze walks more softly in this room—and sometimes removes his cap.

Next to his wife, the beautiful Miss Compson, his chief passion is shrubs and flowers. He has spent thirty-five thousand dollars in decorating his grounds with rare specimens.

It was but a short time ago that the entire Famous Players-Lasky studio revolved around the personality of James Cruze. Everyone, from Mr. Zukor down to the most obscure reader was in search of another "epic" for him.

At last, Harry Carr, a Los Angeles newspaperman, sold them the idea of filming Old Ironsides. With characteristic stupidity the company started making the picture in the middle of an unsettled California spring. It was the first week in July before the sun t shone enough to allow Cruze to have the cameras turned more than two hours in succession.

With hundreds of men on an island in the Pacific in too close proximity to Hollywood, Cruze began, with the help of Lawrence Stallings, who knew little of pictures, and of different film notables, who knew less than Stallings, a newcomer, to make the epic hodge-podge of the sea called Old Ironsides.

The film cost nearly two million dollars. Half of this amount might have been saved had the film been started when it should have been—in more settled weather.

The love story was written into Old Ironsides by James Cruze for the entertainment of the American herd. He has since absolved Mr. Stallings from all blame in connection with the imitation of Elinor Glyn. The story was perhaps more banal than anything ever concocted in the love-sick brains of drivel writers since men and women decided they needed a license to populate grave yards.

But the film magnates had said that Old Ironsides must he an epic. It was the tawdriest epic ever conceived in the befuddled brains of men.

The sad manipulators of art for the multitude looked at their misbegotten child in the projection room and immediately begin pinning the scarlet letter of blame on each other. Then all decided to blame Cruze—the one man among them who had ever made a genuine contribution to the screen.

Peter B. Kyne was engaged to write the titles. He resigned in favor of Rupert Hughes.

The titles were intelligent—and blended the proper measure of patriotism with good English. There were a few good details in the films—and— the rest is silence.

When Lincoln finally learned to let one of his generals alone, he began to win battles.

It is quite possible that had this picture been made as far away from Hollywood as was The Covered Wagon it might have been a great film.

(Continued on page 116)

(Continued from page 114)

Save in ballad form and then only in the mood of a gargantuan vulgarian does Cruze care for song. He has contempt for The Clowns Lament in Pagliacci. He dismisses it with: "The guy pities himself because his wife left him."

His mansion—on twelve acres of ground—is always open. He calls it his "road house". Few people really know him though he has many friends.

He has no politeness of speech. He will say the most terrifying things to one's face. When the person has gone —he says nothing.

Often have I been firmly convinced that there were no nuances in his mind.

And then—that which I have written contradicts me.

If civilization consists in allowing each human complete expression— then Cruze is, at least, a civilized barbarian. His guests are only requested to say nothing of a racial nature. He does not wish to offend his negro servants—who have been with him for years.

I once gave him a play to read. It was the story of a simple negro giant's moral and physical disintegration.

Three days later I asked his opinion of it. He sat, bent over, with his elbows on his knees. His immense hands held his strong jaws a long time.

"God—what you did to that big beautiful man."

George Jean Nathan concurred in this opinion months later.

Gathered about him for five years was the same group of helpers. They have since been disbanded by B. P. Schulberg, the associate producer for Famous Players-Lasky, who has said, "The day of the individual in pictures is over." A sad day, indeed.

Cruze, a dominating and inarticulate Rabelais, deadens the pain of the inner urge with ribaldry and song.

If his sensibilities were a trifle keener; if he were just a bit more sensitive, he would be possibly, a greater artist and a less successful commercial director. He has a corporation and not an artistic conscience.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now