Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowJohn Riddell: A Product of His Times

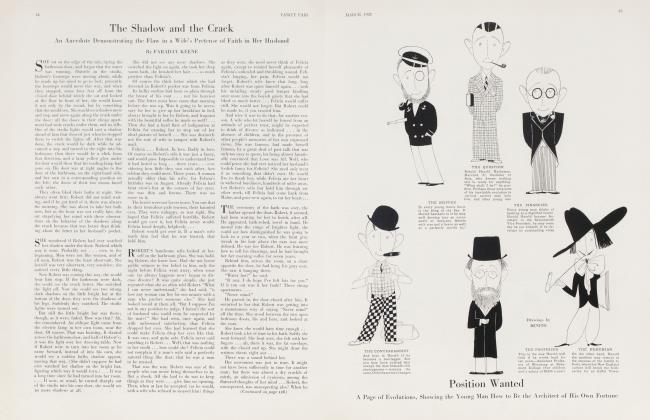

JOHN RIDDELL

A Parody Summary of the Biography Market, and Other Literary Gossip of the Month

INTRODUCTION:

ONE would never say that John Riddell was perfect. Heaven forfend! Aside from everything else, such a statement would be entirely contrary to the modern trend in Life and Letters, and would automatically eliminate him at once as the prospective subject for a best-selling current biography. Let us not consider John Riddell, the paragon on his pedestal; let us consider, rather, John Riddell the Man, with all his faults and all his human frailties, his amours and eccentricities—John Riddell, that strange and paradoxical combination of Henry Ward Beecher, Wilson, Bismarck, George Sand, "Boss" Tweed, Genghis Khan and Lindbergh—as presented for the first time in this amazing biography compiled by his intimate and warmest admirer, John Riddeli

JOHN RIDDELL

Among My Books,

New York City

DEDICATION:

To JOHN RIDDELL

1.The Puritan Riddells

IDSUMMER, 1813 . . .12

John Riddell lay in swaddling clothes, frowning intently . . . Already the Grand Army had been shattered on the plains of the Dneiper26, but in Litchfield, Conn., the young ladies of .Miss Sally Pierce's Female Academy18 still tripped under the saucy elms to the flageolet, and a young baby, sucking his toe meditatively, must needs remove it from his mouth when Nurse enters hurriedly with his Imperial Granum37. . . And in another year the smoke of Washington, burning, will drift down the Potomac . .

"I lie here day after day," wrote John Riddell that summer to Susan Anthony, "in my crib, attempting to reconcile the facts of existence. Whenever I succeed in getting my toe into my mouth, for example, Nurse brings in my Imperial Granum and I only have to take it out again. Why is this? How can I reconcile Imperial Granum with God? . . . Nurse has just come in and changed me again; that is twice today. How can she understand these things? Change is flux, and flux is existence. . . . Where is God in all this?

From far-off Brooklyn already came the sounds of hammering and sawing; the elders of Plymouth Church121, apprised of his coming, were enlarging the chancel and re-inforcing the pulpit . . . On the Tribune27 the city-editor called a young reporter to his side. "Lyman Riddell," he said, "has a baby son."

Forty years later Horace Greeley60 was to remember this.

And in another crib, that pleasant summer afternoon, a brown-eyed baby girl tore open a heavy manilla envelope with her chubby finger. "Dear Lib," she read, "are you doing anything tonight? Suppose I pick you up in my carriage at the usual time, and we'll see if there's really a hell. Bring your bottle. J. R."237 But old Lyman Riddell18was not to be fooled. "Dearest," the brown-eyed baby read later that afternoon, "Father has forbidden my meeting you. Sorry. John." And, below, "P. S. There is a hell. My father just gave it to me." 99 Little Riddell pounded the bars of his crib vainly with his fist. Why? Why? Why? What is hell? Can we believe the doctrines of Calvin?24 In 1863, we shall abolish slavery.

"America shall be free."36 If he could only find something to get sore about in the meantime. He wept for rage; and his black Nurse, not understanding, changed him for the third time that day, crooning a snatch of song he would not hear till many years later:

"Riddell, Riddell, is my name, Riddell till I die.

I never loved Mis' Tilton,

I never told a lie."97

In the Cafe de la Regence 216 Theodore Tilton was to reach his hand patiently across the chess-board. "Your move, I think."8

2.John Enters Princeton

In September, 1875, a tall, thin, somewhat angular young man, who was distinguished by the fact that he wore a tall silk hat with an orange feather stuck in the band, walked into Princeton village carrying a ministerial-looking black bag that had belonged to his father. There is a popular story extant that, immediately on his arrival at college, Johnny Riddell rushed to the library and took out Kant's Critique of Pure Reason. This is absolutely false. The book was in his bag all the time.

On the other hand, the young Riddell lost no time in displaying the qualities of leadership which were destined to distinguish his career in later years as President of the United States of America. While Riddell was Captain of the Princeton football team, such an opportunity arose. It was the outset of the game with Yale, and Riddell, as usual, had won the toss. With the football tucked under his arm he suddenly raised his hand and beckoned the Yale Captain to him.

"Mr. Captain," said Johnny Riddell calmly, and in his attitude could be seen those qualities which were later to distinguish his political career during the most crucial years in American history, "either you will concede this game to us at once, on a1 14-0 basis, or I shall walk off the field with the ball—" he paused significantly—"and the referee's whistle."

"Would you consider 9-6?" offered the Yale Captain nervously.

"You heard my offer," replied young Riddell coldly. "I shall give you three minutes, sir." And he commenced methodically to deflate the bladder of the pigskin.

"But can't we compromise?" begged the Yale man in desperation. "You take the ball, and we keep the referee's whistle?"

Riddell glanced at his watch, folded up the football and tucked it carefully into his wallet. "Mr. Referee," he said in the quiet voice to which some day all Europe would listen with awe, "I must trouble you for your whistle. Princeton has won."

This signal victory was naturally the occasion for considerable rejoicing in Jungle Town; the bells of the chapel rang wildly, and "Riddell's Fourteen Points," as they came to be known, are still discussed in Princeton today.

3.Contempt For The Reichstag

"Here in the Landtag, where I am writing to you ... I am in great difficulties. Already I am Count of Prussia, in charge of his Emperor's land forces . . . but I feel myself constantly handicapped—nay, more; non-plussed, by the fact that I don't speak German. . . . You have no idea how this cramps me, mein freund (my friend). The only thing I can remember is 'Du bist tvie eine Blume', and so far I have had little or no opportunity to work this into my military orders. ... Perhaps you will be so good, therefore, as to slip a German dictionary into the package of clean laundry you are mailing Tuesday ... I am also out of socks (schtockens) ..."

Thus does Herr Riddell write from Berlin to Motley, the friend of his youth; and such are his sentiments during the first months of the reign of "Blood and Iron." Perhaps there is a grim note of fatality in the wordless fears of this Prussian Junker, for in twenty-eight years he is to be overthrown. Perhaps in his next letter to Motley he senses this impending tragedy:

"Tell Fannie . . . that the button is missing again from the sitzplatz of my long woolen underclothes. This has happened ja several times, and I tell you (Gott verdammen) she must in the future more careful be, because it is difficult for me to reach around behind myself every time and sew it on again . . . My love and kisses to Elsa."

(Continued on page 110)

(Continued from page 67)

Is it any wonder, then, that this man is known already to his associates as "The Iron Chancellor"?

4. Riddell and Chopin

And yet, despite this grim exterior, there was a streak of the most tender romance in Riddell the Man; and this capacity for deep emotion found full though brief expression in his illstarred affaire with Chopin. Although Riddell had never met the object of his affections, he had heard often that Chopin and George Sand were lovers; and his tragic misunderstanding was no doubt due in part to the fact that he thought all along George Sand was a man.

"George Sand or no George Sand," he said passionately, one day, "I shall marry Chopin."

"C'est impossible," said his friend Schiller, or Twiller. "Chopin is a man."

"Ha, ha, there's where you're wrong," laughed Riddell gleefully. "There's where everybody gets fooled. She's really a woman. Chopin is just the nom de plume she used when she wrote 'The Mill on the Floss'."

"No, it's the other way round," insisted the friend. "George Sand wrote 'The Mill on the Floss,' and she's the woman."

"Are you sure?" asked Riddell dubiously.

"I'm positive," replied Twiller, or Miller. "We had it in school."

"Well, if George Sand is the woman," smiled Riddell philosophical, ly, "then I suppose my love-affair with Chopin is up the creek." Yet it was easy to see that this tragic end to his little romance had cut him deeply; and, according to some authorities, was directly responsible for the career of vice and corruption to which he abandoned himself, resulting in the famous "Riddell Ring" which caused so much suffering to New York City the following year.

5. "Black Friday"

New York in those days was not the New York of today. In those halcyon times, for example, a stage-line started from the Public Library, circled Bryant Park to avoid the construction which was then under way, turned east on Broadway and ran down James G. Blaine, who was attempting to cross the street. Blaine was later rebuilt on the site of what is now Madison Square Garden; and it was here, in 1892, that Harry K. Thaw shot Stanford White, who built Grant's Tomb. (The Tomb was hurriedly demolished the following year, when it was discovered that Grant hadn't died yet.) At this time, Times Square consisted of a few scattered shanties (later Nedick Orange Booths) and the parking problem was practically nil. "Abie's Irish Rose" was still running, and another had feature was the mosquitoes. The subway had not yet been heard of; and even if it had, it wouldn't have been believed.

Upon this credulous and struggling city, Riddell and his sinister circle descended like a flock of grim vultures, ready to pluck the very heart of the people. The "Riddell Ring" had its origin on January first, in Riddell's law offices on Duane Street; and among this grim four, Jay Gould, President Grant, James Fisk, Jr., and "Boss" Riddell, was hatched the famous Santa Claus conspiracy, which resulted in "Black Friday," the Gold Corner, yellow button shoes, and the blizzard of '88.

(Continued on page 112)

(Continued from page 110)

At that time it was the custom of charitable organizations about the city to dress their employees in red coats and white whiskers, representing Santa Claus, and send them out to ring bells and collect coins at strategic points about the city. Armed with this information, Riddell and his three confederates bought four Santa Claus suits, stationed themselves on the four corners of 42nd Street and Fifth Avenue (then the Aquarium), and commenced to ring their bells. In no time they had amassed millions.

Yet, like every good plan, it had its flaw; and Nemesis appeared in the shape of George Jones, editor of the New York Times (then "The National Geographic"). Glancing over his newspaper with an eagle eye, this canny editor discovered that the date was February 19th, almost two months after Christmas. His suspicions were aroused. In vain the Riddell Ring offered him five millions of dollars to suppress this tell-tale date. Jones would not be bribed (not with five million, anyway) ; the Santa Claus scandal was exposed by Nast in his famous cartoon "Is There a Santa Claus?"; and the Times' relentless campaign spelled for Riddell the beginning of the end.

6. Riddell Khan Conquers The World

In the meantime, two problems had to be solved before Riddell Khan could lead his army against the Muhammedan Turks. Already he had conquered western Asia and Cathay; now his ambitious eye coveted the wealth of Persia and Europe. The world of Islam was before him; yet he hesitated.

The first problem concerned the suit of chain-mail armor which, according to ancient tapestries and paintings on Chinese vases, he invariably wore. A pair of chain-mail trousers, he found, were all very well to stand around in; but, when riding horseback, they were apt to bunch up under him very uncomfortably. Upon dismounting, even after a very little distance, he would resemble a waffle for hours afterward. It was no wonder, therefore, that the brave Mongol hesitated at the thought of riding two thousand miles thus clad, seated on his swift-footed white charger.

Moreover, there remained the second problem of transporting the horde of a quarter million warriors from Lake Baïkul across the Alps into Persia—a problem rendered doubly difficult by the fact that he would have to cross Persia first to get to the Alps. With these problems Riddell Khan dealt in his own way. He called into consultation at once the chieftains and sons of the Khan.

"We shall take the troops by railroad," said Riddell Khan.

"But that is impossible," said Riddell Khan's youngest son, Otto Khan. "Railroads were not invented until 1869."

"Are you sure?" asked Riddell Khan dubiously.

"I'm positive," replied Otto.

"How did I get there, then?" he asked.

"You made your famous march by horseback," explained the youngest Khan, "amid starving and deprivations untold, overcoming the terrors of vast deserts, the barriers of mountains and sea, and the ravages of famine and pestilence, until you achieved your goal at last."

"That's great, Otto," said Riddell Khan, unbuttoning his chain-mail trousers with a sigh of relief, "that's saved me quite a lot of wear and tear."

7. New York's Welcome

The return of "Riddy" after this conquest of Europe was an event unprecedented in American history. Amid the frenzied cheering of millions, eager to greet this slim young Lochinvar out of the West, the "Lone Eagle" marched up Broadway from the Battery to Central Park under a veritable June snowstorm of tickertape and torn-up telephone books, hailed on all sides as America's Ambassador of the Air, he who flew with Faith upon his left, Hope in the cockpit, and Charity chinning herself on the propellors. George M. Cohan composed a song in his honor: "When Riddy Comes Home". Medals, scrolls and keys of the city were presented to him at banquet after banquet, Presidents and Senators elbowed to pay him tribute, women flung themselves before him, and motion-picture magnates offered him million-dollarcontracts.

Yet through all this hysteria "Riddy" remained the same shy, earnest young man he had always been. With a modest smile he declined the fabulous offers, and sought politely to evade the tributes heaped upon him. Despite all these honours heaped upon him, he said, he only wanted to return with his famous typewriter to his humble desk in the offices of Vanity Fair, where he could devote himself once more to his duties as book reviewer, and read the new crop of biographies which awaited him.

"Lives of great men oft remind us," said John Riddell plaintively, "we can make our own sublime."

And so he has.

(HENRY WARD BEECHER: AN AMERICAN PORTRAIT, by Paxton Hibben. Doubleday, Doran.)

(WOODROW WILSON: YOUTH AND PRINCETON, by Ray Stannard Baker. Doublcday, Doran.)

(BISMARCK: THE STORY OF A FIGHTER, by Emil Ludwig. Little, Broivn.) (GF.ORGF, SAND: THE SEARCH FOR LOVE, by Marie Jenney Howe. John Day.) ("Boss" TWEED, by Denis Tilden Lynch. Boni and Liveright.)

(GENCHIS KHAN, by Harold Lamb. McBride.)

(WE. by Charles A. Lindbergh. Putnam.)

"FOR ALL MY YOUNG READERS"

Reviewing juveniles in these ultrasophisticated pages would be a little more remarkable but for the fact that the books are so remarkable themselves. For it has been my pleasure this past month to encounter for the first time that unique series of "Boys' Books for Boys", written by David Binney Putnam and Deric Nusbaum and other young explorers and fostered by the House of Putnam; and these several accounts of actual adventures in the Arctic, the desert and tropical seas, set down conscientiously and laboriously by twelveand fourteenyear-old boys for other boys of their age to read, constitute at once the most astute publisher's attack upon the ancient citadels of Frank Merriwell and the Rover Boys and the rest of the juvenile blaa, and likewise the most refreshing and eager reading I myself have done in a dog's age. I did with them, in fact, what I very seldom do; and that was to finish the last page and then immediately turn back to the first page and start reading over again.

(Continued on page 114)

(Continued from page 112)

It is scarcely literary style that makes them such rattling good reading for young or old. David and Deric write only the normal, healthy, slightly embarrassed descriptions of the things they see, that any other boy could read without the unpleasant suspicion that he is being read to by his great-aunt. Perhaps it is the eager crest of adventure that rears out of each paragraph of the day-by-day hardships and the happy mishaps of the trail; perhaps by their very ingenuous manner they catch that same miraculous feel of discovery that is in Beebe and Hurley. Certainly, amid the present gaseous seepage of Halliburton and Harry Hervey and the rest of the Tuesday-Afternoon-Ladies'Club travel-writers, these books come like a clean and decent wind.

(DAVID GOES TO BAFFINI.AND, by David Binney Putnam. Putnam.)

(DERIC AMONG THE INDIANS, by Deric Nusbaum. Putnam.)

GREAT SNAKES

Despite my relentless prejudice against all lady-explorers, from the notoriously camera-shy Mrs. Martin Johnson to Richard Halliburton, Dragon Lizards of Komodo by W. Douglas Burden seems to me a peculiarly fascinating volume. To be sure, Mr. Burden has taken his Companion in the Adventure of Life (to whom the book is overwhelmingly dedicated) along with him down to the Dutch East Indies to see the lizards; but even such recurrent scientific camera-scoops as "Mrs. Burden on Her Way to Breakfast" or "The Author's Wife at the Raffles Hotel, Singapore, with her Friend 'John Bear' ", with which the pages are affectionately peppered, do not entirely cloud this remarkable tale of a Lost World in one of the most colourful island groups known. The fantastic photographs of half-mythical monsters recommend this book inevitably to the adventure-hungry audience which gobbled Trader Horn.

(DRACON LIZARDS OF KOMODO, by W. Douglas Burden. Putnam.)

IN LESS WORDS THAN IT TAKES TO TELL

THE GREVILLE DIARY, edited by P. W. Wilson. $10. (Doubleday, Doran.) The skeletons in the Buckingham palace closets rattle in a hollow cadaver as Mr. Wilson turns page after page of this highly readable, highly mischievous biography of the times of Queen Victoria. The fact that it has been banned by King George in England should give added impetus to its Chicago sales.

THE BEST STORIES OF 1927, edited by Edward J. O'Brien. (Dodd, Mead.) Just as pretentious a failure as ever.

TOMBSTONE, by Walter Noble Burns. (Doubleday, Doran.) The month's best Western: a grand and gory history of Arizona, straight from the hip, by the sharp-shooting author of the equally fascinating "Saga of Billy the Kid". A darned good yarn.

(Continued on page 116)

(Continued from page 114)

FROM GALLEGHER TO THE DESERTER, by Richard Harding Davis. (Scribners.) A deserving collection of Davis' best, well edited, well presented and well worth having.

CLAIRE AMBLER, by Booth Tarkington. (Doubleday, Doran.) Whether it falls from the lips of Penrod or Willie Baxter or this current paste-board puppet, Miss Ambler, the old Tarkington patter is just as readable and just as shallow as ever. A good book to take in a train, and leave there.

FUN AND FANTASY, by E. H. Shepard. (Methuen and Co., London.) Mr. Shepard of "Punch" abandons Winnie-the-Pooh for the moment to show what he can do in the field of humorous drawing and, by comparison, what most American artists can't.

SAVAGE ABYSSINIA, by James E. Baum. (Sears.) The expedition of the Field Museum of Chicago ventures into country-never-visited-by-whitemen in search of the rare nyala, the walia ibex, greater kudu, oryx, zebra, waterbuck, hartebeest, roan bushbuck, gazelle, gerunhuk, and when better animals are found, Baum will find them.

But—Is IT ART?, by Percy Hammond. (Doubleday, Doran.) This most urbane critic and sparkling stylist of our newspaper dramatic columns gathers his random observations together in a book of wit and magnetic charm, which belongs on your list of intelligent reading.

GREAT DETECTIVE STORIES, by Willard Huntington Wright. (Scribners.) I always get a kick out of detective stories. And Mr. Wright, who seems to enjoy them as much as I do, has picked out the seventeen masterpieces that were calculated to give me the biggest kick of all. Between us, we had a swell time.

AN AMERICAN DOSTOIEVSKY

Samuel Omitz's HAUNCH, PAUNCH AND JOWL was an unforgettable performance and, according to the publishers, is still and deservedly selling widely. As E. M. Forster would say, HAUNCH, PAUNCH AND JOWL "came off". Mr. Omitz's new book, A YANKEE PASSIONAL, is a no less powerful effort but it does not "come off." It is all there in gross verbiage, passion, observation, people, satire, but the total profit for the industrious reader is, in comparison, extremely slight, although the book has been called the American Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. It is punctuated, here thinly, there lavishly, with portions of a treatise on Catholicism that give it as a work of fiction a sad sag. Mr. Ornitz is most convincing in his projection of the life in the poverty-stricken quarters of the New York of the 1890's, but a half dozen of writers have wrung as much or more value out of the same kind of milieu. On every page is the imprint of the author's (worthy) determination to be Great, to be Real, to be an Author of Consequence. One suspects in the author—it is only a suspicion—a little of le precieux ridicule in a new and uniquely Americo-literary sense. At any rate, just like Dostoievsky, he has written a nice, big, thick book.

(Continued on page 118)

(Continued from page 116)

(A YANKEE PASSIONAL, by Samuel Ornitz. Boni & Liveright.)

BY ONE WHO KNOWS

E. M. Forster has done a good book for those who are born novelists, those who would become novelists, and those who have novels thrust upon them. It is hard to conceive the mind which would not find this book gay, informative, and above all authentic. Mr. Forster kicks aside all the academic robes and trappings at once, rests one thigh lightly across a corner of his desk, and chats unaffectedly with bis class about his likes and dislikes, bis theories and his conclusions. It is not criticism, it is advice; it is not advice, even, but an informal and delightful commentary on novels and their aspects by an acknowledged master of the subject of which he speaks, who is gifted with an engrossing style and an epigrammatic brevity of phrase and a nice knack for swift parody which enables him to show up all an author's faults in one revealing flash. He scores his point with laughter, and underscores it with a patient and fair consideration of the subject as a whole that makes supremely good reading—whether you are a novelist or a layman or even a critic. (ASPECTS OF THE NOVEL, By E. M. Forster. Harcourt Brace.)

TWO MASTERS

Of the importance and artistic merit of THE GATEWAY TO LIFE by Frank Theiss, and THE COUNTERFEITERS by Andre Gide there can be and probably will be very little dispute: both are the work of superb craftsmen. Both M. Gide and Herr Theiss are masters of their subjects, their situations, and their media, and both have produced works about which, technically, one can only say that they are faits accomplis.

Widely divergent as these two novels are, it is necessary to remark their kindred connotations in order to appreciate the full significance of what message they bring and of what degree is the excellence of their material quite aside from their obvious technical supremacy. Both are, in their essences, mirrors of the generation which the war is only now bringing forth.

THE COUNTERFEITERS, superficially considered, is almost completely a study of decadences. It is concerned with perversion and crime, with sordid infidelities and polite deceptions. It is the story of brilliant young men entangled in the morasses of a social system too complicated for their understanding, and its climax—if the book can be said to have any climax —is the reckless and brazen suicide of one of the finest characters.

THE GATEWAY TO LIFE is the story of this same generation, set now in Germany instead of France. The book is more sharply centered in the group whose significances in both novels are greatest—young men in a university, struggling not with a system too complicated for their understanding, but with one so simple in the restrictions and limitations of its tradition that their passion to escape it is even stronger than that of the other group, and all the more difficult of accomplishment because they have come to the hand-to-hand place of battle without the preparations of campaigners who have had first to fight their way to the battleground. And in this book also the apex seems to be the suicide of a youth, a youth whose tragedy is not that he does not know but that he knows too well.

Of the two books bracketed here, THE COUNTERFEITERS is, both in its content and its technic, the more suggestive and the more important. The astounding and perfectly balanced intricacies of its construction are handled in a way that is to be contrasted with the "influences" and plagiarisms of most books, intensely original. M. Gide has opened avenues of subject and form to the literature of the future, the importance of which can as yet be only guessed. Judged absolutely, the book is probably not "great," but it stands with The Magic Mountain, far above all the rest of current w-riting, as one of the two impregnably first-rate books of the year. (THE COUNTERFEITERS, by Andre Gide. Knopf.)

(THE GATEWAY TO LIFE, by Frank Theiss. Knopf.)

A SUPERNATURAL TRIANGLE

A FAIRY LEAPT UPON MY KNEE, by Bea Howe, is a delightful fantasy in which two lovers are separated by the appearance in their lives of a fantastic little creature, neither human nor mythical. The entomologist-hero, William, leaves his fiancee in London and goes to the country to catch his usual spring collection of moths. Alas! he finds not moths but a fairy—a fairy far from being in the tradition of love, light, and sunshine. From that point on it is a charming and unique variation of the old triangle.

It seems to me a great mistake that the publishers insist on the classification of Miss Howe's work with that of Sylvia Townsend Warner and David Garnett. True, it has all the delicate exaggeration and satire of the work of either of these two authors. But it combines with their hair-line wit a tendency toward the most tangible realism. In the creation of her two chief characters Miss Howe has embodied two people who are unmistakably real and recognizable in almost anyone's world, characters built up with strokes as swift, keen andsure as those of the most trenchant realist.

(Continued on page 124)

(Continued from page 118)

(A FAIRY LEAPT UPON MY KNEE, by Bea Howe. Viking.)

KING, QUEEN AND NAVE

So—in LOVE IN CHARTRES by Nathan Asch—she ran away from all the bridge-parties and new-born babes and general deadliness of any middleWestern town, and went to Paris to be —oh, different, anyway. But she found Paris quite as dull and small a world as the one she had left behind her. In a desperate attempt to escape herself by escaping from everyone who could remind her of what she intrinsically was, she went blindly across France, and found herself soon in Chartres, her soul at last unmoored and flying free along a radiant path of light streaming on her through blue stained glass. And in the blue stained glass she found him, and they went to live together in a tiny apartment within walking distance of the famous glass—she could afford it—and there was room in the apartment for the table at which he would write the next great American novel. But alas, they had not, as the saying goes, "given their right names." So in the end they go separate ways, but the blue window is still there, and if the book is worth anything at all it is as publicity for Chartres.

This sort of book is really just too bad. It has no claim to distinction: the prototypes are stupid and worthless, the style is imitative and none too skilful as imitation. Its only departure from thousands of manuscripts which publishers are forced to read and fortunately spare the public is in its exposition of a parlor-trick in which, the author has confessed, he takes a special pride: the sleight-ofhand way in which he avoids naming his hero and heroine throughout the book.Perhaps the trouble is there: that no one, not even the author, gave his right name.

(LOVE IN CHARTRES, by Nathan Asch. A. & C. Boni.)

AUTOBIOGRAPHY UNDER PRESSURE

In THE LOCOMOTIVE GOD, William Ellery Leonard has attempted to recall and set down all the facts in his life which have finally made of him an hysterical neurotic. The first cause of this near-insanity was the tremendous

shock he experienced at the age of four when a locomotive, which he visualized as God, swept past him on a placid summer afternoon. From that day to this Mr. Leonard traces the course of his life, proving conclusively to himself—and, after all, why should he have to prove his life to anyone else—that he is what he is because of that unbearable impact on the nervous system and fearful imagination of a sensitive child. As a record of complexes, 'phobias, and plain lateVictorian nerves, it could offer very little to anyone except an intellectual introvert. As the record of an amazing life and no dwarfish intellect it should have a prominent place on the shelves of those who believe that autobiography is one of the most interesting and important classes of literature. But the chief value of the book is in the quality of its writing, the acute mentality behind the polish of the work, and the philosophical aspect of a book which was never written with intent to philosophize.

(THE LOCOMOTIVE GOD, by William Ellery Leonard. Century.)

MORE POWER

The heroine of Lion Feuchtwanger's THE UGLY DUCHESS is Margarete of Tryol, ruler of a duchy in Germany which has been riddled by the extravagance and shiftless generosity of her father. She marries once to save her country from dissolution and once again to bring it a sane prosperity. Her love she gives in pity to a man as ugly as she. Her life and her hate she negates in the interest of her country. And for these great gifts she is given the bitter reward of contempt and fear because they are forever shadowed and thwarted by the beauty of another woman whose soul is as hideous as Margarete's body. Deprived finally of love, children, and power, she surrenders herself to the sordid pleasures which the man she loved had taught her—to sleep, to lust, to eat. Without life, without intelligence, she sinks into the negative act of existing, and finds herself in the only period of her life which approaches any state of contentment.

Posed against the tumultuous, glowing background of mediaeval Europe, Herr Feuchtwanger has painted a full-length portrait of a woman— somber, ugly, incongruous. From a welter of petty intrigue and malice there rises the titanic figure of a great woman who sacrifices everything in her life to make her country powerful, and whose fate it is to be hated and feared for her physical ugliness. The picture has been drawn with crude strength and bases its claim to artistry on no pretentious technique, hut rather on the barren ruggedness of its simplicity.

(THE UGLY DUCHESS, by Lion Feuchtwanger. Viking.)

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now