Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowMeaning No Offense

Parody Interviews in the Respective Manners of Frances Newman and Carl Van Vechten

JOHN RIDDELL

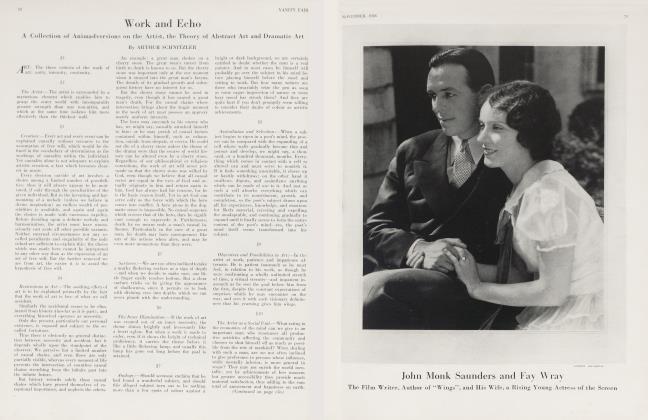

EDITOR'S NOTE: In this article Mr. John Riddell writes a parody interview in the manner of Frances Newman with due deference to Dead Lovers Are Faithful Loves and, for good measure, also relates his experiences in Hollywood in the manner of Spider Boy by Carl Van Vecliten. The parody in the manner of Miss Newman has particular interest in that Mr. Riddell, who has been considered among the most reticent of critics, has revealed at last a hitherto unsuspected and extremely intimate secret of his very private Love Life. In the Van Vechten parody Mr. Riddell tells of his recent sojourn among the movie stars in Holl3rwood and how he was lavishly entertained by such celebrities as Charlie Chaplin and Mary Pickford. These two parodies-together with others which have appeared previously in Vanity Fair-have been included in a sensational volume of strange interviews by John Riddell entitled Meaning No Offense, brilliantly illustrated by Vanity Fair's artist, Miguel Covarrubias. The book will be published in late October by the John Day Company

DEAD NOVELISTS ARE GOOD NOVELISTS

WHEN the little male cuckoo that was only a wooden cuckoo hopped out of a tiny mahogany door to cry his name three times in six beautifully separate syllables, Isabel Evelyn slipped off the long black-clocked sheer silk stocking from her beautifully-tended right foot. And when she slipped off the long black-clocked sheer silk stocking from her beautifully-tended left foot, the little wooden cuckoo did not hop out of his tiny mahogany door to cry his name in two more beautifully separate syllables, because it was only three o clock and a fourth "Cuck-oo" right then would have sounded silly. But when she stood up and slipped off from her beautifully-rounded shoulders the beautifully-embroidered white chemise which her mother had bought her for $2.98 in Gimbel's Basement, the little male cuckoo did open the tiny mahogany door and hop out again just for a moment, on the pretext that he had forgotten his rubbers, because he was only a wooden cuckoo but after all he had the instincts.

When she had laid the beautifully-embroidered white chemise across the bottom of a bed that was a book-case in the daytime, she walked across the yellow hooked rug which her father's great-grandmother had hooked from a furniture store in Fall River in 1843, toward the little mahogany dressingtable that was not a mahogany table if you scratched the surface too hard with a pin. And she looked into the experienced and slightly jaded mirror at the dark henna hair and blonde lashes and delicately lifted cheeks and carefully modelled nose and carefully remodelled chin which she had assembled into a fairly satisfactory reflection after eight years' hard work.

Then she walked across the yellow hooked rug into her bathroom, and she looked into the full-length mirror, which had been presented to her by the son of two Chicago packers because it was the precise reflection of her beautifully-tended figure, at the familiar arrangement of hair and eyes and nose and lips, which could be called a face, if you were being general enough. And then she looked down at the delicately curved throat, and the voluptuous arms, and the two round firm white objects which reminded her of two round firm white pint-bottles of cream which the Borden's man left on her doorstep every morning, but which of course were really only her two fists clenched tightly before her, because a heavy golden shell of pain had just burst in the center of her body for fear that John Riddell did not love her.

And then she walked across the yellow hooked rug into her library, and she looked into the full-length novel which was the precise reflection of her beautifully-tended mind. And she looked at the beautifully-tended prose of the novel, and the familiar arrangement of verbs and nouns and adjectives and adverbs, which could be called a style, if you were being general enough. And then she looked down at the delicately curved allusions, and the voluptuous paragraphs, and the straight description which went to the middle of her novel, and the green pattern of delicately confused metaphors, and the plot that became two strangely divided parts that did not seem to have any relation to each other. And she thought of the moment when she had first wanted to see John Riddell's sleeping face turned toward her prose, and when this strange desire had united with her familiar style and when it had become her novel.

When she placed her beautifully-tended right foot into the bath which was just too cool for the 21st day of October, she was thinking of the two forked veins which would weave their delicately green lines up John Riddell's sun-burned forehead when he first lifted her purple jacket and looked beneath it at her novel. And when she placed her beautifully-tended left foot into the bath that was just too warm for the 19th day of October, she was wondering if she would hear him pronounce it perfect in two beautifully-separate syllables, or whether she would hear him pronounce it less than perfect in one. But when she lay upon her back in the bath that was precisely right for the 20th day of October, and the surface of the water covered all of her beautifully-tended body except the two round firm white objects that were her knees, she was wondering if she could ever make him love her as much as she loved herself.

Fifteen minutes after she had stepped into the bath, into which she had dipped herself as carefully as one of the South Carolina Pages had never dipped a slice of bread-andbutter into his coffee, Isabel Evelyn looked into the full-length mirror at the body which she was drying delicately with two cotton towels for which her father had sacrificed a cotton night-shirt that had come from Bloomingdale's in 1896. And she looked away from the full-length mirror to look into the fulllength novel at the beautifully-tended prose which she would lay in the waiting arms of John Riddell when the large hand pointed to twelve and the small hand pointed to four on the clock of the Graybar Building on the west side of Lexington Avenue between 43rd and 44th Street.

When she had carefully and quickly curled very long brown sentences into a careful reproduction of the smooth sentences on which John Riddell would open his eyes, and when she had very quickly and carefully covered every inch of her prose with a delicately pink and a delicately lilac feminine lure, she began to open jars of white cream marked "French phrases" and jars of pale crimson marked "exotic phrases" and jars of a slightly deeper crimson marked "biological and pathological phrases", as she might have lighted white candles before her photograph, and she poured out her pale crimson phrases as she might have poured out holy water.

But before she opened the door that led into the street where she would find the noth Street subway station, she stopped to open a little six-cornered glass bottle with a square purple label marked "French Love Drops, the perfume of ecstasy, just a tiny drop is enough" which she had purchased for .98 postpaid from the Wons Company, Box 367, Hollywood, California, and to lay the point of the long glass stopper on her words and on her sentences, and to slip it along the paragraphs that were beginning to quiver with a caressing pain, and then to slip it down every inch of the beautifully-tended novel that she was going to lay in John Riddell's waiting arms.

When she had not reached into her pocket because there was no pocket in the chemise she was not wearing, and when she had dropped into the subway turnstile a single round piece of silver for which the Government of the United States of America stood ready to offer her five cents at an instant's notice, Isabel Evelyn looked at her delicately pink and delicately lilac and delicately naked body in the small mirror of a subway slot-machine. And when she entered the crowded subway car that was to carry her to John Riddell, a heavy golden shell of pain burst in the very center of her body and she lifted her hands to grasp two round firm white subway-straps swinging overhead. But when the first jerk of the swaying car sent her off her beautifully-tended right foot into the lap of the man in front of her, and the next jerk of the swaying car sent her off her beautifully-tended left foot into the lap of the man behind her, she began to wonder whether she would have time to sit in all the laps of all the men in the car before she got to Times Square, or whether she would have to ride as far as Pennsylvania Station, and walk back.

Continued on page 104

Continued from page 89

She looked again at her beautifullytended body in the reflection on the polished floor of Grand Central Terminal, and a heavy golden shell burst within her as she felt more eyes on every inch of her novel at the present moment than had ever been on a single inch of her before. She felt that the whole city of New' York was pressing toward her, and examining her delicately-pink and delicately-lilac prose, and reaching for her voluptuous words, and feeling her paragraphs, and pushing and jostling and trampling each other in their eagerness as they followed her across Grand Central Terminal, and into the elevator, and up to the nineteenth floor of the Graybar Building. But when she looked around eagerly, there was nobody in the car but the elevator boy, and he was asleep.

The large hand of the clock was pointing to twelve and the small hand was pointing to a sign marked "Out of Order" as she walked through the empty offices of Vanity Fair toward the office in which she would find John Riddell. But when she had entered this office, and looked under his desk, and in his wraste-basket, and behind the water-cooler, and through the Outgoing Mail, and among the backnumber-files, and over the transom, and beneath the small card marked "Gone for the day, J. R.", the conviction began to grow upon her that he was not there. And a heavy golden shell burst within her as she realized that'she never would be any nearer to him than she was now, if he could hejp it, and that he never could love her as much as she loved herself.

When she wras passing the window of the thirteenth floor of the Graybar Building, Isabel Evelyn was wondering whether it might not have been really more fitting for Posterity if she had decided to go back home, after all, and climb into the bath-tub and let the beautifully-tended body that was not to be her body after she had passed twelve more stories sink slowly to oblivion beneath the water which would have been only slightly scented with heliotrope bath-salts that she could have bought for $1.49 at the second counter on the right in the rear of Saks-Fifth Avenue. And when she was passing the window of the eighth floor, upside down, a position which she had modestly assumed by this time in her descent, she was wondering if, when they had laid her ⅛ a long box which was not the long box in which Gimbel's had delivered the beautifully-embroidered white chemise that she was not wearing, John Riddell, bearing a single phallic lily in his hand, would reverently place upon her crossed hands a $15.00 wreath of laurel and of bay from a Fifth Avenue Florist, with a Tiffany engraved card marked "Now She Belongs to the Ages." But when she was passing the window of the third floor, she was w'ondering whether, after she had passed the first floor, there would be anything of her left to the Ages, except possibly a slight stain on the west side of Lexington Avenue between 43rd Street and 44th Street.

DKAD LOVERS ARE FAITHFUL LOVERS. By Frances Newman (Liveright).

HOLLYWOOD BOY

Owing to the congenital appeal of Ambrose Deacon for himself, the limited appeal of his novels had never really satisfied him. Before his announcement of Hollywood Boy, to be sure, he had enjoyed a modest reputation, if not a reputation for modesty, in the world of letters. His stories of the local color in Harlem had been accepted as sophisticated by mailclerks and milkmen, he had eaten in the Algonquin and written feelingly about cats, and his rapidly cumulating essays had been published in rapidly culminating volumes.

Nevertheless, prior to the announcement of Hollywood Boy, the world, artistic or cinema, had never appreciated him half as much as he had appreciated himself. Now, however, he had suddenly become a Hollywood celebrity of gratifying if local importance. He had been photographed shaking hands with Charlie Chaplin, Mary Pickford had elected him an Honorary Vice-President of the Our Girls Club, and he had proved one of the most popular fiances Patsy Ruth Miller had had in weeks. Clara Bow devoted an entire article in Photoplay to comparing him favourably to Gilbert Roland.

Arriving in the world of the cinema with nothing but his own opinion of himself, he had proceeded at once to establish himself as the Don Juan of this remarkable community; and now, seated in his magnificent suite in a luxurious bungalow of the superlative Hotel Ambassador, and surrounded by the exotic gals of the fourth largest profession in the world, he permitted himself a slight sigh of weariness. How different—he loosened the panting arms of Bebe Daniels from about his neck—how different life seemed to him now, since he had become the most sought-after figure in Hollywood. How different, Ambrose reflected, shifting Marion Nixon to his left knee, from his former easy obscurity. He uncoiled Esther Ralston from about his knees, and slung her fretfully across the floor. And yet. . .

As Jack Riddell approached the door of Siesta—summoned from his ranch near Santa Fe by his old friend's tricated a gal from the wriggling heap before him. You here again, Stella, the Star Gazer? he chided, heaving her irritably through the door. That's the fourth time she has sneaked in here, he sighed to Jack Riddell. She even follows me out at night, and writes up my house in Beverly Hills. . .

Continued on page 108

Continued from page 108

Do you own a house in Beverly Hills? marveled Jack.

Well, not exactly, hesitated Ambrose, but I have an understanding with the real-estate people. $1000 down and $1000 a year for thirty-five years. I have the same understanding about my Rolls-Royce. And at nights it is filled with the Hollywood elect.

. . . He enumerated them vaguely from a little list in his hand. . . Loretta Young, and Sue Carol, and Camilla Horn, and Mary Duncan, and Lilyan Tashman, and Mary Brian, and ZaSu Pitts. . .

Ambrose, interrupted Jack Riddell suddenly, I have got to find out. . . I have got to know. What is the secret of your sudden popularity here? Why do these beautiful gals surround you? Why is all Hollywood at your feet?

My fame as an author, blustered Ambrose.

Nonsense, said Jack impatiently. One has only to read your

books to know it couldn't be that.

Ambrose looked about him carefully and lowered his voice.

Well, it's really a secret, Jack, he began. When I came here, you see, I knew I should have to adopt some novel plan to secure the adulation I craved. So very subtly—I think I mentioned the matter to Louella Parsons —I spread the word that I was going to write a novel about Hollywood. You know what these beautiful gals will do for a little publicity. The scheme worked like a charm. I awoke to find myself popular at last. And yet. . .

Aren't you satisfied? cried Jack, noting w'ith astonishment the look of longing that had suddenly come over his friend's face.

And yet sometimes I long to be out of it all. . . Ambrose's face shone with a new light. . . Sometimes I want to return to Newr York, and meet Carl Van Vechten and Carl Van Vechten, and Carl Van Vechten, Carl Van Vechten, and Carl Van Vechten, and Carl Van Vechten. . . After all, he is the only person who really appreciates me. . .

Jack Riddell groaned.

SPIDER BOY, by Carl Van Vechten. Knopf. I

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now