Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowHow To Know Our Feathered Cousins

Some Helpful Spring Hints on Attracting Our Bird Neighbours to the Very Doorstep

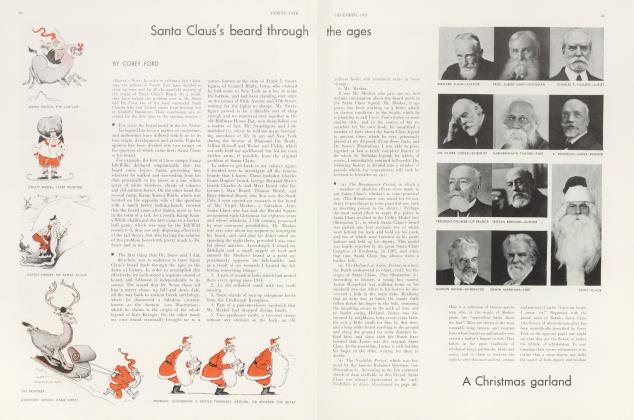

COREY FORD

IT is a well-known fact that birds make ideal neighbours. I know that for several months last summer we lived downstairs under a family of Purple Martins; and not once during this time were we annoyed by late parties or falling plaster. They were more than obliging whenever we shinnied upstairs to borrow a couple of eggs; and despite their habits (I admit that it might have been a little pleasanter, for example, if we had lived upstairs) we found them agreeable and obliging in the extreme. We were indeed sorry to leave this roomy bird-house and move back to our smaller apartment in the city for the winter.

It was this agreeable experience with the Purple Martins, as much as anything, that first interested me in the problem of attracting and caring for our feathered cousins ("Daddy Corey's Chickens", as my friends have come to call them) ; and so greatly have my activities succeeded, indeed, that I am already becoming known around Larchmont Gardens as the Great Brother of the Birds, or, more familiarly, the Big Canary. It is in an effort to pass on to others the pleasure and profit that I myself have derived that I am setting down these few hints on Caring for Birds about the Home.

RIGHT next door to the house where I live is a man named Mr. Batchelder, a dandy fellow and quite a nature-lover himself. He is very fond of birds, preferably in fricassee, and naturally quite a little friendly rivalry has sprung up between us to see which one of us can attract the larger number of birds to his doorstep. Mr. Batchelder, for example, has rigged up a very attractive bird-bath in his back yard, out of an old sewer-pipe and a china wash-basin, and every morning he watches his feathered friends at their ablutions through a crack in the shutter. On the other hand, I have built a cozy little bird-house just behind the garage, and last night I brought home a couple of wrens and we had a swell time.

Both Mr. B. and I have had so much fun together out of our little "Nature Club" (the initiation fee is only fifty cents, and you get a slick celluloid button) that Mr. Batchelder wondered yesterday whether the untold hundreds of other bird-lovers in Larchmont Gardens might not be interested to hear some of the little experiences and adventures which we have encountered in our dealings with birds, in order that they might profit by our examples. If enough people in Larchmont Gardens can be persuaded to start attracting birds, Mr. Batchelder and I thought, then perhaps their dooryards will be filled with these gay songsters in the early morning, and we can get a little sleep.

So that was how this little article came to be written.

The first thing to remember in Attracting Birds to the Home, both Mr. Batchelder and I have discovered, is to win their confidence. Birds are notoriously shy; and the least unexpected movement, such as firing a shotgun into their midst, will drive them away for hours. If proper care and tact are not observed in approaching one of these timid creatures, the little rascal will only dart into the air, flirt its tail and reply: "In your hat."

♦Author of "Twenty Years Among the Cassowaries", "Do Robins Tell?" and "Up in Phoebe's Nest"

In order to overcome this natural reticence, therefore, Mr. Batchelder and I have endeavoured to mingle with the birds and act just like one of them; and for this purpose we have borrowed a couple of old Indian suits, sewed with feathers, from some little boys. Bright and early every morning, clad in these suits, we perch on our window-sills and hop down to the lawn, crawling on our hands and knees over the grass and pretending to look for worms. (Ugh!!) We have also learned to whistle like birds, or very nearly like birds; and when we are perched on a high branch of my willow-tree, chirping for dear life, the neighbours passing below can scarcely tell our song from that of the feathered folk. "What are those two clucks up there?" I have actually heard them say.

Once he is in the confidence of the birds, the novice doubtless will next desire to photograph them in their natural haunts. Personally Mr. Batchelder and I have tried every conceivable device to "snap" the birds, such as climbing a tree after them (a plan rendered impractical owing to the fact that they fly away), hiding the camera, or disguising ourselves as a clump of rhododendrons; but all in all we have discovered that the best method to photograph a bird in a natural pose is to crawl up behind it and pot it with a 22rifle, after which the bird may be stuffed and photographed at leisure. This is the method used by prominent African big-game hunters today.

The construction of a Bird-House, in which the birds may reside during the summer, is a task requiring considerable study and forethought. Each bird requires a house especially adapted to its peculiar needs; and oftentimes too large a dwelling is as bad as no dwelling at all. A comfortable average home, I have discovered, is that located in my own yard, which contains eleven rooms and two baths, a kitchen and sleeping porch, laundry, and garage attached. There is also a large garden surrounding the house, and in the center of this garden is located the Bird-House I was speaking of. This BirdHouse was built as follows:

I FIRST selected an ordinary soap-box, such as may be secured at any corner grocery-store, and then proceeded to knock it apart and saw up the wood into a number of smaller pieces, about 6" x 10" x 6" x 10", and proportionately long. Selecting a broad flat surface (in my case, the kitchen floor) I then nailed four upright boards and my thumb into a large rectangle, over the top of which I constructed a solid frame, about 14" from the base. This gave me a square wooden skeleton to work upon. I next proceeded to nail all the remaining pieces of wood across this frame, laying them one alongside another, until I had it completely enclosed, except for a tiny hole in the front, which I promptly filled in, enclosing it completely. 1 then sawed out the section of kitchen flooring on which I had built my model, and stood it up on end. As a result I found I had the same soap-box 1 started with.

My next move was to go to a nearby bird-store and to buy a nice little Bird-House.

When the construction of the Bird-House is thus completed, the next problem confronting the novice is how to set it up in the garden so that birds will live in it and rear their young; for a Bird-House without birds is about as useful as a Bird-House with them. Most feathered creatures, except horses, prefer to nest at a fair height from the ground; and for this purpose it is wise to select a tall oak pole, about 20' in height and 0" in diameter, on which the house may stand. This pole should be painted some dull color and hammered into the ground in a secluded corner of the garden.

The difficulty of hammering a twenty-foot pole into the ground may well be imagined; and I will confess that Mr. Batchelder and I were for the moment nonplussed. However, we solved the problem at last by the simple device of securing a second twenty-foot pole, exactly like the first, and hammering it into the ground a few inches away from the desired location. All that we had to do then was to shinny up this second pole with the hammer in our teeth and perch on the top, from which point of vantage we were able to pound the first pole deep into the ground, until it was steady enough to bear the weight of a bird-house. We then climbed down and pulled up the second pole, and threw it away.

Continued on page 124

Continued from page 77

Our only remaining problem, once we had the pole erect, was how to nail the bird-house up on top.

The bird-fancier who has succeeded in attracting these feathered cousins around his home, must not forget that his duties as a host also include feeding the little pets; and it was only after much experimentation that we finally developed a satisfactory bird-food to meet all conditions.

We first took a mixture of raw grains, such as corn, barley, oats and rye, all properly ground, and. cooked them thoroughly so as to render them soluble for the birds' tiny gullets. This we accomplished by steaming them under pressure, after which Mr. Batchelder mixed in some ground malt which he happened to have in his kitchen. We kept the resultant bird-mash at a temperature of 145 F. by successive additions of hot water. We then drained off the saccharine infusion, when it had acquired its maximum density, into a jug containing some yeast, and let it stand a week or two.

Our next step was to pour this solution from the jug into a queer-looking, dusty apparatus which l had found in my cellar, and which consisted of a copper vessel with a closed head that connected with a spiral tube. We kept this tube submerged in cold water, and heated the bird-mash in the copper-kettle, sniffing it now and then so as to make sure that all the little robins and chickadees and wrens would have just the best li'l' ol' feed they ever had in Larchmont Gardens. In the meantime, of course, we were catching the little brownish drops of liquid which commenced to trickle slowly through the end of the spiral tube into a tumbler held out for the purpose; and, for want of anything better to do with them, we drank them. We prepared several tons of bird-food in this fashion, I think, in the course of the afternoon; and so excellent were our results that before we were through I found that I could imitate without difficulty a Yellow-Bellied Sap-sucker (long an ambition of mine) ; while Mr. Batchelder, by locking his heels over the chandelier, could give a credible impression of a mother humming-bird feeding its young. Needless to say, our bird-food was voted an over-whelming success.

In fact, that is probably Mr. Batchelder you can hear splashing around in his bird-bath now.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now