Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowA Novelist's Laboratory

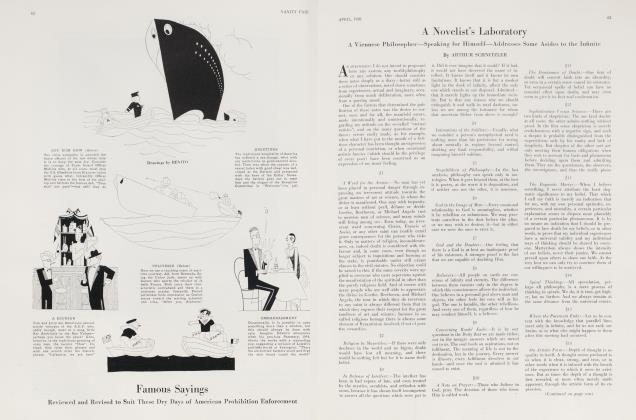

Noting Further Precipitations of Humanity in the Test Tubes of the Austrian Philosopher

ARTHUR SCHNITZLER

§1

THE Tender Passion Among Nations:— The wish, the impulse, or the passion to undergo the expediences and the sufferings of a spiritual relationship are usually at work in us even before a desirable or suitable object has been found. And it is rarely the case that we summon patience enough to wait for the proper object.

In fact, it is highly questionable whether, in any specific instance, the ideal object exists at all. To choose an example from the most popular emotional relationship, love—it is doubtful whether two people are ever fitted for each other in the sense that one or the other, or both of them, would never have loved if they had not happened to meet.

Man wants to love, wants to hate, just as he wants to feel malice, indignation, envy, reverence. And thus he will generally manage to find an object for his emotions in the direction of the least resistance, even though it may not seem to be the ideal subject. Thus, some quite trivial incentive may lead to love, which in turn degenerates into passion; and similarly an aversion which has arisen from perfectly negligible causes may often grow, or encourage itself to grow, into a condition of hatred.

The spirit of hate is perhaps still a greater power in the world than the spirit of love. And in the relations between groups—as for instance nationalities—there is always greater proneness to hatred than to love.

One group may, it is true, be seized by an enthusiastic admiration for an individual; but we will certainly never see an instance of two groups with an attitude of enthusiastic admiration for each other, at least not in any matter of importance. And we have yet to see in history the case of one nation annexing itself to another, or annexing itself with enthusiasm, even when impelled by a common hatred for a third. Thus as has been repeatedly demonstrated in politics, a league of nations has only an ephemeral value.

§2

The Apology, and the Audience:—The refusal to make amends was an event which first occurred when the situation had ceased to be a secret between the two persons involved. For no sooner is a third party let into the matter, no sooner are disinterested outsiders initiated —as inevitably happens—than the situation which was heretofore an exclusive concern of two people takes on fresh life from the participation of others: It is given a new form, receives added meaning, transmitting its effects on and on until finally it mysteriously reverts to the two men between whom it first arose.

§3

Two-Dimensional Personality:—A man's character can probably be determined from three apt anecdotes with the same precision as in calculating the area of a triangle from the position of the three fixed points which, when joined, make its sides.

§4

Brilliant Villains and Stupid Heroes:—A man's talent will often reconcile us to the questionableness of his character, if we do not have to suffer in any way personally from it. But we are never inclined to let ourselves become more leniently disposed through the excellence of a man in the face of his lack of talent.

§5

The Core-less Man:—In many people the mind seems to consist of isolated, unattached elements which never group themselves about a centre and are thus unable to form a unit. So the core-less man lives enormously alone, though he is never completely aware of this. The great majority of people are core-less in this sense; but it is only in persons of note and importance that we perceive such dispersion, which is most noticeable in those having a gift for art, especially actors of genius, and above all, actresses.

§6

The Margin of the Unimaginable:—There are some people who are forever denied satisfaction, and are terrifically bored in the very midst of some experience, no matter how important it may be. For they have long since lived through it in the imagination. But the true artist of life is thankful for the humble surprises which he usually meets with in the course of some trifling experience, or at least which he dares look forward to.

§7

Neutral Partisans:—Our worst enemies are by no means those persons who hold other opinions than our own, but those who, while they think as we do, are prevented for various reasons—such as caution, squeamishness, or cowardice—from owning up to their views.

§8

Pandora:—The heart is created to love and to hate, to be happy and to suffer, to exult and to complain. But if it strives to understand, since understanding is the province of the mind alone, it sins against its own nature. And when it finally believes that it does understand, it merely deceives itself, and thereby perishes.

§9

The Latin Genius:—As there is hysterical love, so there is hysterical hate, which has all the symptoms proper to other hysterical effects: the partly; voluntary, partly involuntary overflowing of the emotions, the tendency towards play-acting in the expression of the emotions, and the necessity for both the overflow and the play-acting.

§10

The Generous Front:—Many a person passes for a man of dignity purely because he does not permit himself to display too vividly his perhaps perfectly justified resentment

against someone who has been more fortunate. If he himself suddenly meets with good luck, we will soon discover that he has always been a shabby fellow.

§11

The Wise Virgin:—Through fear of disappointment, he repeatedly allowed good fortune to pass him by. And he was worse deceived than the man who took every opportunity that was offered him, even at the risk of its turning out in his disfavour.

§12

The Baptism of Words:—You imagine that you have transformed a man by your gifts for pedagogy; yet you have usually made of him purely a comedian, a hypocrite or a coward.

§13

Judas the Joiner:—Goethe: "Blessed is he who shuts himself off from the world without hate." But cursed is he who feels that he must keep himself open to the world while hating it.

§14

Two Loves Without Lust:—The love for children is always an unhappy one, and is in the last analysis the only love that deserves to be called such. But let us have the courage to remember. In our own love for our parents —however great it may have been—was there not a little pity, and perhaps even some aversion : and finally, did not this love have about it something which is akin to horror?

§15

Sine Nobilitate:—The snob is a man who strives after apparent self-improvement by methods which lead to self-abasement. He is the true masochist of the social order.

§16

Quod Erat Fakiendum:—There are three stages of development required in counterfeiting the emotions so as to produce that state of mind which we .call sentimentalism. In the first stage, the emotion is weakened by too much knowledge of itself; in the second stage it is distressed at the inability to conceal this knowledge; and in the third it is degraded by its pride in this inability, whereupon it finally earns the right to be called emotion.

§17

Commonness of Common Interests:— Nothing does so much to make the world more dreary as the obligations of common interests. This erroneous belief brings people together who should have no connection with one another, and keeps others apart when they should be associated. Moreover, it requires reputable people to take sides with the paltry and thus to become paltry themselves.

§18

The Therapeutics of the Feelings:—There is no more of a lull in the relations between people than in the life of the individual. There are beginning, development, climax, descent, and close; and just as with the individual, there are all sorts of disorders: ailments, chronic illnesses, states of exhaustion, symptoms of age—nor is hypochondria lacking. Many relationships even succumb to children's diseases, though these can also be kept alive by attention, good care: in a word, intelligent hygiene. Others are taken off in the prime by intercurrent illnesses, and still others die sooner or later of functional disturbances which are seldom diagnosed in time. Some age quickly, others slowly, many are comatose and can be brought back to life by patience, by application of the proper remedies, by good will. But human relations also resemble human beings in the fact that they rarely adapt themselves to the inevitable necessity of bearing pain and old age with dignity, and of knowing how to die in beauty.

(Continued on page 106)

(Continued from page 48)

§19

The Grand Style:—Human relationships which began on the grand style cannot be reduced to a lower plane without the most painful and humiliating sacrifices. It is wiser simply to break up a common spiritual menage than to make a laborious attempt to restrict it.

§20

Symptoms:—Tn an ailing relationship, as in an ailing organism, we must interpret even the apparent trifles as symptoms of the disorder.

§21

Reliable Fish:—Within the economy of human relations, a combination of unreliability and warm-heartedness is always to be preferred to a combination of reliability and cold-heartedness. For whereas we have a protection against unreliability in our knowledge of human nature, cold-heartedness makes every human relationship so hopelessly frigid that it remains condemned to sterility.

§22

The Closed Garden of the Soul:— If you cherish too jealously the jardin secret, the secret garden of your soul, it may easily come to bloom too luxuriantly, to grow beyond its allotted space, and in time to occupy areas of your soul which were never meant to be kept secret. Thus, your entire soul may finally become a closed-in garden; and, for all its bloom and fragrance, may perish of isolation.

§23

The Noble Hate:—Every really great emotion can be noble and fruitful—hate as well as love. Only it must be free from contaminating elements of egotism, envy, vindictiveness and cowardice. But how much purification must love first undergo before it can be looked upon as truly selfless?

§24

Beyond Intellect:—We get to a certain place in life, experience, and knowledge of human nature where all converse, even with the cleverest and most amiable of our friends, has hardly more than atmospheric significance; and all our discussions, however profound we might call them, can no longer enrich us or delight us intellectually, hut appeal to us as rhythm or music.

(Continued on page 108)

(Continued from, page 106)

§25

Sociable Solitude and Other Kinds: —There are more kinds of loneliness— and they are purer, more painful, and more profound—than that which we usually think of as such. Has it never happened to you that while among some large gathering of people where you have been perfectly at ease, suddenly all those present appear like phantoms to you, and you seem to be the one real person among them? Or when carrying on some highly engrossing conversation with a friend, have you never become convinced of the complete meaninglessness of your words and of the impossibility of your ever understanding each other? Or did you never, while resting contentedly in the arms of your mistress, suddenly become aware that behind her brow she was thinking thoughts of which you suspected nothing? These are all direr forms of loneliness than that which we usually designate by the term—the state of being alone with ourselves. For when measured by all those other real aspects of loneliness, with their strangeness, peril, and despair, the usual sort is seen to be a state of harmless meditation, and we should rather consider such separation from others as the mildest and most amenable form of sociability.

§26

Preening Hermits:—Loneliness also has its coxcombs; and they betray themselves by posing as its martyrs.

§27

One Way Through the Ether:—How precious loneliness is when we know that somewhere in the world, even though in the remote distance, someone is thinking of us with yearning. But is this really loneliness? Isn't this rather a more agreeable and irresponsible kind of sociability, which contrives to demand and to receive without ever giving anything in return, yes, without even acknowledging its indebtedness?

§28

A Tragedy of Two Mirrors:—When two people wish to understand each other profoundly, it is exactly as though two mirrors put face to face were to reflect their own images again and again, and still again, with desperate eagerness, until they finally lost themselves in the horror of a hopeless distance.

§29

Ideas and Men:—Often when we believe that we hate a man, we only hate the idea which he represents. And when we actually confront the individual who had seemed unbearable or even dangerous, we find nothing but a poor wretch who was born to sin, to suffer, and to die—and our hatred changes into sympathy, compassion, perhaps even into love.

§30

The Prodigal:—If some truth which you uttered out of deep conviction comes back to you on another's lips like a proverb, you are often tempted to receive it as the father receives the prodigal son who once fled into the world laden with riches and now returns to knock at the door as a beggar.

§31

The Only Pure Relationship:— Your implacable and deadly enemy is doubtless the one man with whom you could have preserved a wholly pure relationship throughout your life— provided that the two of you never came to know each other personally.

§32

The ZJmeanted Gift:—Of all spiritual extravagances, the most useless is justice. Whatever love one squanders is often repaid, even though in modest measure. But in return for justice we receive nothing but misunderstanding, ingratitude, and disdain.

§33

Anatomy of Reconciliation:—If you feel inclined towards reconciliation, first ask yourself what really made you so kindly disposed—a poor memory, opportunism, or cowardice?

§34

The Difference:—Why does the good-heartedness of others usually seem to us like stupidity, and our own like virtue—the virtue of others like weakness and our own like a proof of noble-mindedness?

§35

To Disillusion:—We may often come to disillusion people through no fault of our own. All that is required for this is that someone who has overrated us or even someone who has judged us according to our worth, should have developed away from us or beyond us, or should merely imagine that he had done so. But we must reassert ourselves again and again, with each new day, by our own efforts and our own powers.

§36

Wanted: a Villain:—When you believe that someone else is threatening to cause your ruin, do not try to lay the blame upon him, but first ask yourself how long you have been in quest of such a man.

§37

Love Your Neighbour: The interest which your fellow man takes in your career is composed in varying proportions of malice, meddlesomeness, and superiority.

§38

The Unpardonable Crime:—A man may have deceived you, robbed you, or slandered you—yet there would always be the possibility of a reconciliation, yes, even of an ideal relationship subsequently arising between you. Once the deed was done, you could even strike up excellent terms with your murderer—with him perhaps readiest of all. The one man to whom there is no access in all eternity—even though you personally have long since got over his offence—is the man who does not know what he did to you.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now