Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

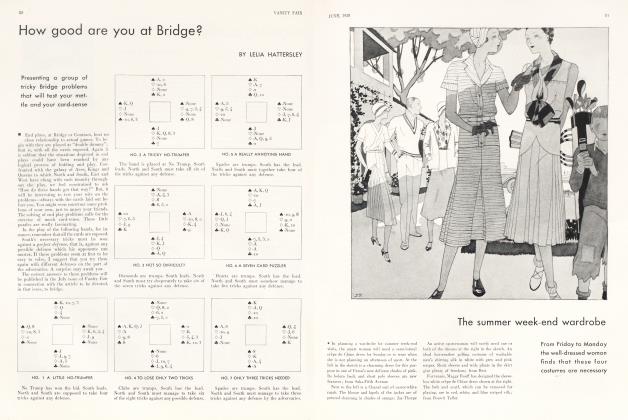

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Nowwho wins at contract?—and why

LELIA HATTERSLEY

the value, in bridge, of psychology, intuition, hunch, or whatever you may call it

Why does one player, although bringing to the game what is apparently the same degree of skill, almost invariably lose at Contract, while another almost invariably seems to win?

We all know Bridge players who have all the rules down pat and play their cards with more than a little ability, and yet consistently lose; and we know others, seemingly quite slip-shod in their methods, who consistently win.

And this brings us to the question: Is there such a thing as continued bad luck or persistent good luck at Bridge? The chronic loser will generally claim that there is, and that he himself is the victim of a relentless jinx which hoodoos his every play. Unbiased observation, however, usually shows that the root of his trouble does not lie in bad cards. It springs rather from a lack of card psychology, from an inability to read the idiosyncrasies, the moods, and failings of his fellow players. The chronic loser always lacks that certain sense which enables him to suspect dangers, to see traps, to know when to do, when to dare, or when to lie low and say nothing.

The player who wins, in spite of the fact that he has never really studied the strategy of the game and could not tell a grand coup if he met one face to face, invariably has this certain something—card-sense, cardpsychology, call it what you will.

It is not always easy to discover why one person persistently loses and another wins, because this element which so largely makes for success or failure at Bridge or Contract is usually manifested in a branch of the game where finesse is most difficult to observe—namely, in the bidding. A clever play seldom goes unnoticed because it is made on the board for all to see and admire. But an equally clever bid may readily pass unobserved. In the general run of contract games, players seldom take note of each other's original holdings or seek to check up on the motive which might have prompted a given declaration. Each one is usually too busy explaining why he did not show a certain suit, lead another card, finesse a different way, and so on.

What happens in an average game of contract is something like this: In competitive bidding against Y and Z, A, being vulnerable, is pushed up to a declaration of four Spades and doubled. Immediately the hand is played with A down three tricks. He rushes into a recital of the extenuating circumstances: certain cards which he expected to find in Y's hand turned up in Z's; every break was against him; Y's bidding was unwarranted, his double ridiculous, etc. If A would only stop to view the situation thoughtfully instead of emotionally, he might learn something to his advantage. Namely, that Y, knowing his psychology as a persistent overbidder, had deliberately used camouflaged declarations to lead him, A, into a wide open trap.

Again, when A and B are bluffed out of their easy game declaration at No Trump by an over-bid of three Diamonds from Y, they are far more prone to bewail their ill luck than to realize that Y may have executed a well planned coup.

Paradoxical as it may seem, it is a wellknown fact that ability to play the cards Avith exceptional skill sometimes develops a chronic loser at Contract. The result is that "bull-dog" type of bidder who simply will not give up a disputed contract. This type is not only easy prey for a discerning opponent, but during any session of Contract his opportunities to hang himself are frequent, and seldom neglected.

At the same time it is certain that the successful Contract player must be endowed with a well developed gambling instinct. This fact is frequently overlooked because in the main, the gambling instinct is only recognized Avhen it evidences itself in reckless and illogical plunging.

Though on the surface the two bear a close resemblance, there is in reality a wide disparity in the card strategy of the farsighted, judicious gambler and the irrational speculator; a disparity which usually marks the line between success and failure. The difference between the two types is fundamental. One embarks upon a speculative bid or play because, after weighing all the odds, he thinks it is worth trying, the other because, without weighing the odds, he hopes it will prove worth trying.

Less frequently than in the bidding, but affording an even greater kick when successful, the play of a hand offers the opportunity for a heady gamble. Here is a case where the declarer was able to make his game contract by anticipating an opponent's reaction to a given situation.

Both sides were vulnerable. South, a keen psychologist, playing with a weak partner against two competent opponents, dealt and bid three No Trumps. Everybody passed, and West lead the five of Hearts. With this lead and East's play of the Heart King, South was confronted by a situation to give any one pause.

He could see that holding up his Ace of Hearts would be worse than useless as the fall of the Jack would immediately betray his fatal weakness in the suit. Including his Ace of Hearts, eight tricks were of course in sight. But how to get the ninth and still escape the menace of the ten remaining Hearts against him?

The obvious venture for his contract would seem to take in his six Clubs and then try the finesse in Spades. But South did not choose the obvious way. He played his Ace of Clubs followed by his King. On this lead East signalled with the seven of Diamonds. Promptly South switched the suit and led his Queen of Diamonds.

To East it now seemed plain that South, being out of Clubs, was trying to coax the Ace of Diamonds and establish an entry in Dummy. As to the situation in his partner's suit, East knew from the rule of Eleven that South held only one remaining high Heart. But there was nothing by which he could place its denomination, nor the unusual length of West's holding. So East passed the King of Diamonds.

His extra trick secured, South took no more chances, but cashed in four Clubs and the Ace of Spades.

(Continued on page 118)

(Continued from page 93)

When the rubber had been scored, South's partner drew him aside, anxious to inquire why, instead of trying the Spade finesse, he had risked the Diamond lead.

"Because," explained South, "the odds in the play were more favourable than in the Spade finesse. The finesse meant a fifty-fifty chance, while it was a hundred to one that East, being a good player, would refuse to put up his Ace of Diamonds. With an inexperienced adversary who wouldn't have realized the danger of establishing an entry in Dummy, or with a super-expert who might have sensed my trap, the odds offered by the finesse would have been more attractive."

Whether or not there is such a thing as card sense, per se, is a disputed question. Some one has put forth the theory that there is a certain bit of the brain which has never been mapped, which responds only to the stimulus of such problems as are found in cards. Fantastic as such a theory seems, we can all enumerate several players among our acquaintances who would seem to bear it out.

There, for instance, is Smithstupid enough at college; a failure in business; as boring a dinner partner as was ever encountered. Put him at a Bridge table to make a fourth with a brilliant author, an affluent bank president, and a world-famed scientist. He will proceed to out-think, out-guess, and out-wit the lot of them.

Then there is Jones who, in the ordinary affairs of life, is accounted little better than a moron. Give him a pack of cards and immediately something clicks in his otherwise dull brain. With far-reaching calculations, he can carry out an intricate plan of defense or attack. With brilliant strategy, he will swing a game in his favour or save a rubber.

From whence are these powers of deduction, inference, and imagination derived? Why do they function only at the card table and remain quite dormant elsewhere?

Of course, all brilliant card players are not morons. Heaven forbid! Many gifted men and women, outstandingly successful in the world of affairs are notable Bridge players: Charles Schwab, Paderewski, and hosts of others. But it is indisputable that a great number of people of real intellectual power can never learn to play more than a passable game; and that there are innumerable couples of marked intellectual disparity where the less intelligent partner, wife or husband as the case may be, entirely eclipses the other at the Bridge table.

The artistic temperament does not seem to offer a fertile soil for the development of good Bridge. Writers, singers, actors, artists, are rarely skillful at the game. But lawyers take to Bridge with amazing readiness. Among business men, the bankers seem to contribute the greatest number of good players.

Do men or women make better Bridge players? Considering the greater opportunity for development, afforded by their more abundant leisure, it is surprising that the women Bridge players do not outstrip their male competitors. That they don't is probably due to the fact that the female of the Bridge species is less daring than the male. At the same time, because a woman is dependable and sticks more closely to the rules, she is often the more acceptable partner to an expert.

Barring the ideal combination of two experts, the happiest partnership at Bridge is made up of an imaginative and brilliant player with a thoroughly dependable routine partner. Many of the best known Bridge teams have been formed from this combination.

There is no partner whom the expert so dreads as the would-be psychologist, the type of player whose erratic tactics are based, not on practical deductions from a given situation, but on his recollection of strategic plays which he has seen made by superior players.

A fact which many players never clearly grasp is that the expert does not disregard a sound rule except for some reason which, at that particular crisis, is sounder than the rule.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now