Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

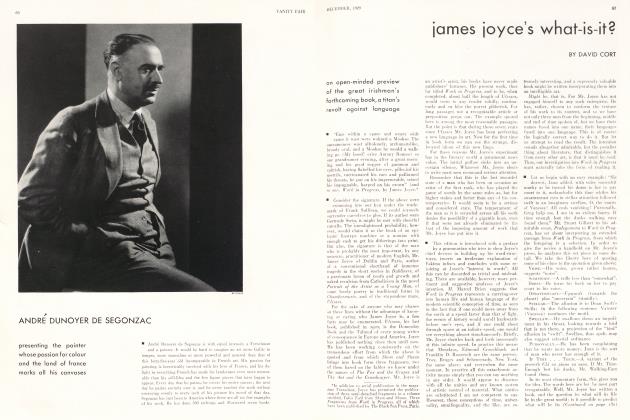

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Nowdead pictures on the walls

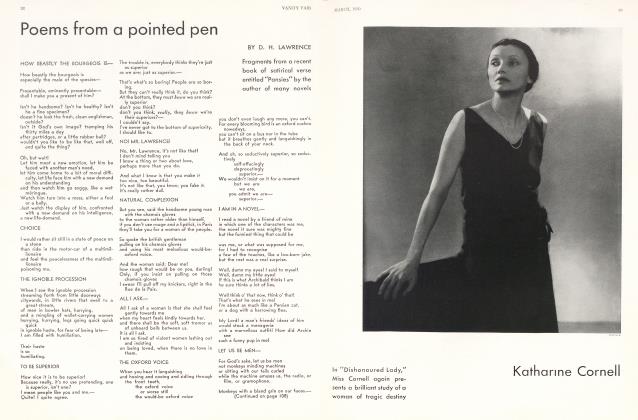

D. H. LAWRENCE

advocating the wholesale scrapping of stale art and the circulation of new and living paintings

■ Whether wall-pictures are or are not an essential part of interior decoration in the home seems to be considered debatable. Yet since there is scarcely one house in a thousand which doesn't have them, we may easily conclude that they are, in spite of the snobbism which pretends to prefer blank walls. The human race loves pictures. Barbarians or civilized, we are all alike; we straightway go to look at a picture if there is a picture to look at. And there are very few of us who wouldn't love to have a perfectly fascinating work hanging in our room, that we could go on looking at, if we could afford it. Instead, unfortunately, as a rule, we have only some mediocre thing left over from the past, that hangs on the wall just because we've got it, and it must go somewhere. If only people would be firm about it, and rigourously burn all insignificant pictures, frames as well, how much more freely we should breathe indoors. If only people would go round their walls every ten years and say: Now what about that oil-painting, what about that reproduction, what about that photograph? What do they mean? What do we get from them? Have they any point? Are they worth keeping?—The answer would almost invariably be No. And then what? Shall we say: Oh, let them stay! They've been there ten years, we might as well leave them!—But that is sheer inertia and death to any freshness in the home. A woman might as well say: I've worn this hat for a year, so 1 may as well go on wearing it for a few more years.—A house, a home, is only a greater garment, and just as we feel we must renew our clothes and have fresh ones, so we should, renew our homes and make them in keeping. Spring-cleaning isn't enough. Why do fashions in clothes change? Because, really, we ourselves change, in the slow metamorphosis of time. If we try to imagine ourselves now in the clothes we wore six years ago, we shall see that it is impossible. We are, in some way, different persons now, and our clothes express our different personality.

■ And so should the home. It should change with us, as we change. Not so quickly as our clothes change, because it is not so closely in contact. More slowly, but just as inevitably, the home should change around us. And the change should be more rapid in the more decorative scheme of the room: pictures, curtains, cushions; and slower in the solid furniture. Some furniture may satisfy us for a life-time. Some may be quite unsuitable after ten years. But certain it is, that the cushions and curtains and pictures will begin to be stale after a couple of years. And staleness in the home is stifling and oppressive to the spirit. It is a woman's business to see to it. In England especially, one lives so much indoors that the interiors must live, must change, must have their seasons of fading and renewing, must come alive to fit the new moods, the new sensations, the new selves that come to pass with the changing years. Dead and dull permanency in the home, dreary sameness, is a form of inertia, and very harmful to the modern nature, which is in a state of flux, sensitive to its surroundings far more than we really know.

■ And, do as we may, the pictures in a room are in some way the key to the atmosphere of a room. Put up grey photogravures, and a certain greyness will dominate in the air, no matter if your cushions be daffodils. Put up Baxter prints, and for a time you will have charm; after that, a certain stuffiness will ensue. Pictures are strange things. Most of them die as surely as flowers die, and, once dead, they hang on the wall as stale as brown, withered bouquets. The reason lies in ourselves. When we buy a picture because we like it, then the picture responds fresh to some living feeling in us. But feelings change: quicker or slower. If our feeling for the picture was superficial, it wears away quickly—and quickly the picture is nothing but a dead rag hanging on the wall. On the other hand, if we can see a little deeper, we shall buy a picture that will at least last us a year or two, and give a certain fresh joy all the time, like a living flower. We may even find something that will last us a lifetime. If we found a masterpiece, it would last many life-times. But there are not many masterpieces of any sort, in this world.

The fact remains: there are pictures of every sort, and people of every sort to be pleased by them; and there is, perhaps, a limit to the length of time that even a masterpiece will please mankind. Raphael now definitely bores us, after several centuries, and Michael Angelo begins to.

But we needn't bother about Raphael or Michael Angelo, who kept up their fresh interest for centuries. Our concern is rather with pictures that may be dead rags in six months, all the fresh feeling for them gone. If we think of Landseer, or Alma Tadema, we see how even traditional connoisseurs like the Dukes of Devonshire paid large sums for momentary masterpieces that now hang on the ducal walls as dead and ridiculous rags. Only a very uneducated person nowadays would want to put those two Landseer dogs: Dignity and Impudence, on a drawing-room wall. Yet they pleased immensely, in their day. And the interest was sustained, perhaps, for twenty years. But after twenty years, it has become a humiliation to keep them hanging on the walls of Chatsworth or wherever they hang. They should be burnt, of course. They only make an intolerable stuffiness wherever they are.

And if this is true of Dignity and Impudence, or Millais' Bubbles, which are pictures that have a great deal of technical skill in them, how much more true is it of cheap photogravures, which have none. Familiarity wears a picture out. Since Whistler's portrait of his mother was used for an advertisement, it has lost most of its appeal, and becomes for most people a worn-out picture, a dead rag. And once a picture has been really popular, and then died into staleness, it never revives again. It is dead forever. The only thing is to burn it.

■ Which applies very forcibly to photogravures and other such machine pictures. They may have fascinated the young bride, twenty years ago. They may even have gone on fascinating her for six months or two years. But at the end of that time they are almost certainly dead, and the bride's pleasure in them can only be a reminiscent sentimental pleasure, or a rather vulgar satisfaction in them as pieces of property. It is fatal to look on pictures as pieces of property. Pictures are like flowers, that fade away sooner or later, and die, and must be thrown in the dustbin and burnt. It is true of all pictures. Even the beloved Giorgione will one day die to human interest—but he is still very lovely, after almost five centuries, still a fresh flower. But when at last he is dead, as so many pictures are that hang on honoured walls, let us hope he will be burnt. Let us hope he won't still be regarded as a piece of valuable property, worth huge sums, like lots of deadas-doornails canvases today.

If only we could get rid of the idea of "property", in the arts! The arts exist to give us pleasure or joy. A yellow cushion gives us pleasure. The moment it ceases to do so, take it away, have done with it, give us another. This is done, and so cushions remain fresh and interesting, and the manufacturers manufacture continually new, fresh, fascinating fabrics. The natural demand causes a healthy supply.

In pictures it is just the opposite. A picture, instead of being regarded like a flower or a cushion, as something that must be fresh and fragrant with attraction, is looked on as solid property. We may spend two or three dollars on a bunch of roses, and throw away the dead stalks without thinking we have thrown away our dollars. We may spend twenty dollars on the cover of a lovely cushion, and strip it off and discard it the moment it is stale, without for a moment lamenting the money. We know where we are. We paid for aesthetic pleasure, and we have had it. Lucky for us that money can buy roses or lovely embroidery. Yet if we pay ten dollars for some picture, and are tired of it after a year, we can no more burn that picture than we can set the house on fire. It is uneducated folly on our part. We ought to burn the picture, so that we can have real, fresh pleasure in a different one, as in fresh flowers and fresh cushions. The aesthetic emotion once dead, the picture is a piece of ugly litter.

(Continued on page 108)

(Continued from page 88)

Which belies the tedious dictum that a picture should be part of the architectural whole, built into the room, as it were. This is fallacy. A picture is decoration, not architecture. The room exists to shelter us and house us, the picture exists only to please us, to give us certain emotions. Of course there can be harmony or disharmony between the picture and the whole ensemble of a room. But in any room in the world you could carry out dozens of different schemes of decoration at different times, and to harmonize with each scheme of decoration there are hundreds of different pictures. The built-in theory is all wrong. A picture in a room is the gardenia in my buttonhole. If the tailor "built" a permanent and irremovable gardenia in my morning-coat buttonhole, I should indeed be unfortunate.

Then there is the young school which thinks pictures should be kept in stacks like books in a library, and looked at for half-an-hour or so at a time, as we turn over the leaves of a book of reproductions. But this again entirely disregards the real psychology of pictures. It is true, the great trashy mass of pictures are exhausted in halfan-hour. But then why keep them in a stack, why keep them at all? On the other hand, if I had a Renoir, I should want to keep it at least a year or two, and hang it up in a chosen place, to live with it and get all the fragrance out of it. And if I had Titian's Adam and Eve, from the Prado, I should want to have it hanging in my room all my life, to look at: because I know it would give me a subtle rejoicing all my life. And if I had some Picassos, I should want to keep them about six months, and some Braques I should like to have for about a year: then, possibly, I should be through with them. But I would not want a Romney, even for a day.

And so it varies, with the individual, and with the picture, and so it should be allowed to vary. But at present, it is not allowed to vary. We all have to stare at the dead rags our fathers and mothers hung on the walls, just because they are property.

Then what? Then ask the department store about it. Don't, for heaven's sake, go and spend a hundred dollars on another picture that will have to hang on the wall till the end of time, just because it cost a hundred dollars. Go to the department store and ask them what about their Circulating Pictures? They have a Circulating Library—or other people have: huge Circulating Libraries. People hire books till they have assimilated their contents. Why not the same with pictures?

Why should not the stores have a great "library" of pictures? Why not have a great "pictuary", where we can go and choose a picture? There would be men in charge who know about pictures, just as librarians know about books. We subscribe, we pay a certain deposit, and our pictures are sent home to us, to keep for one year, for two, for ten, as we wish: at any rate, till we have got all the joy out of them, and want a change.

In the pictuary you can have everything except machine-made rubbish that is not worth having. You can have big supplies of modern art, fresh from the artist; etchings, engravings, drawings, paintings; you can have the lovely new paintings that most of us can't afford to buy; you can have frames to suit. And here you can choose, choose what will give you real joy, and will suit your home for the time being.

There are few, very few great artists in any age. But there are hundreds and hundreds of men and women with genuine artistic talent and beautiful artistic feeling, who produce quite lovely works that are never seen. It is a tragedy that all these pictures with their temporary loveliness should be condemned to a premature dust-heap. For that is what they are. Contemporary art belongs to contemporary society. Society at large needs the pictures of its contemporaries, just as it needs the books. Modern people read modern books. But they hang up pictures that belong to no age whatever, and have no life, and have no meaning, but are mere blotches of deadness on the walls.

The living moment is everything. And in pictures we never experience it. It is useless asking the public to "see" Matisse or Picasso or Braque. They will never see more than an odd canvas, anyhow. But does the modern public read James Joyce or Marcel Proust? It does not. It reads the great host of more congenial and more intelligible contemporary writers. And so the modern public is more or less up-to-date and on the spot about the general run of modern books. It is conscious of the literature of its day, moderately awake and intelligent in that respect.

But of the pictures and drawings of its day it is blankly unawmre. The general public feels itself a hopeless ignoramus when confronted with modern works of art. It has no clue to the whole unnatural business of modern art, and is merely hostile. Even those who are tentatively attracted are uneasy, and they never dare buy. Prices are comparatively high, and you may so easily be let in for a dud. So the whole thing is a deadlock.

Now the only way to keep the public in touch with art is to let it get hold of works of art. It was just the same with books. In the old days there was no public for literature, except the cultivated class. The great reading public came into being with the lending library. And the great picture-loving public would come into being with the lending "pictuary." The public wants pictures hard enough. But it simply can't get them.

(Continued on page 140)

(Continued from, page 108)

And this will continue so long as a picture is regarded as a piece of property, and not as a source of aesthetic emotion, of sheer pleasure, as a flower is. The great public was utterly deprived of books until books ceased to be looked on as lumps of real estate and came to be regarded as something belonging to the mind and consciousness, a spiritual instead of a gross material property. Today, if I say: "Doughty's Arabia Deserta is a favourite book of mine," then the man I say it to won't reply: "Yes, I own a copy,"—he will say: "Yes, I have read it." In the Eighteenth Century he would probably have replied: "I have a fine example, in folio, in my library," and the sense of "property" would have overwhelmed any sense of literary delight.

The cheapening of books freed them from the gross property valuation and released their true spiritual value. Something of the same must happen for pictures. The public wants and needs badly all the real aesthetic stimulus it can get. And it knows it.

There are thousands of quite lovely pictures, not masterpieces, of course, but with real beauty, which belong to today, and which remain, stacked dustily and hopelessly in corners of artists' studios, going stale. It is a great shame. The public wants them, but it never sees them; and if it does see an occasional few, it daren't buy, especially as "art" is high-priced, for it feels incompetent to judge. At the same time, the unhappy, work-glutted artists of today want above all things to let the public have their works. It is necessary that adults should know them, as they know modern books. It is necessary that children should be familiar with them, in the constant stream of creation. Our aesthetic education is become immensely important, since it is so immensely neglected.

And there we are—the pictures going to dust, for they don't keep their freshness, any more than books or flowers or silks; yet their freshness means hours of delight. And the public is pining for the pictures, but daren't buy, because of the moneyproperty complex. And the artist is pining to let the public have them, but daren't make himself cheap. And so the thing is an impasse, a simple state of frustration.

Now is the opportunity for the department stores and their lending library—or "pictuary"—of modern works of art. Or, better still, an Artists' Co-operative Society, to supply pictures on loan to the great public.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now