Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Nowthis community business

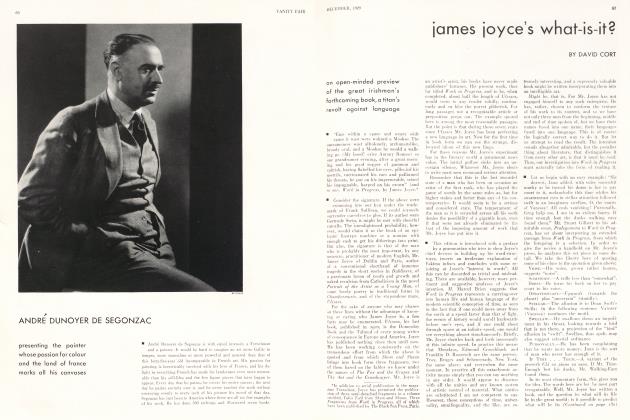

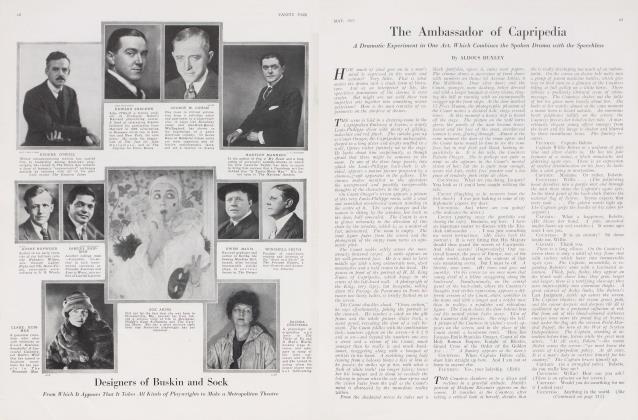

ALDOUS HUXLEY

a lone individualist views the creed of death to the one for the good of the many

The two countries in which the attentive traveller will hear the word 'community' most frequently pronounced are India and the United States. It is a case of extremes meeting. The ancient civilization, coeval with that whose remains are dug up at Tiryns and Troy, joins hands with the newest of modern civilizations. Progress turns out, as usual, to have been in a circle, or at best in a spiral.

I am by temperament extremely anti-social, a born anarchist whose profession fortunately permits him to indulge his congenital dislike of contacts and co-operations to his heart's content. I therefore deplore the contemporary reaction against individualism and towards what I may call groupism. I am a protestant against the current community-worship. I have the gravest mistrust of that 'spirit of social service' which our educationists are forever trying to instil—only too successfully, I fear— into the minds of their defenceless charges. If I were a millionaire, I should endow great schools and universities, where the young should be brought up as non-co-operators and enemies of society, ferociously independent. But I am not a millionaire; and even if I were, my endowments, as I know too well, would be perfectly useless. They could not stay the tide; it sets too strongly against individualism. The whole force of contemporary circumstances is marshalled against the individual; Fate itself, the Genius of our Age, the Spirit of Modern History, are all on the side of the group. Community-worship and the spirit of social service are merely the expression in idealistic terms of a brutal state of facts. Whether we like it or no, the great majority of us must sacrifice our individualities to organized society. There is nothing for a born anarchist to do but, with the best grace possible, to accept the existing order of things. Not, however, without an occasional protest to relieve his feelings. Hence this article.

A recently published volume by M. Alphonse Seche, La Morale de la Machine, contains what is, so far as I know, the best and briefest summing-up of contemporary tendencies which has yet been made. So excellent, indeed, is the summing-up, so gruesomely true, that the book positively made my flesh creep, when I read it. La Morale de la Machine is, for me, the Writing on the Wall— definite, inescapable and terrifying.

"Our age," says M. Seche, "is entirely dominated by the will to power of the machine." The mechanization of industry has directly or indirectly affected every human activity. Of the effects of mechanization on society at large I shall not speak in this place; for my theme is the individual. Suffice it to say that, in the purely political, economic and social spheres, the machine has been, on the whole, a beneficent agent. Mechanization, it is true, has greatly enhanced the horrors of war; but this must not blind us to the fact that it is a force tending in the long run to produce universal peace. It has raised the economic condition of the working classes. Its complicated existence is demonstrating the absurdity of political democracy as a system of government and is everywhere gradually imposing (in some countries has already imposed) a more rational and efficient system. These are benefits for which we should be duly grateful to the machine. But in this world it is impossible to get something for nothing. Everything must be paid for, either on the nail or by instalments. What society has gained by mechanization, the individual is losing.

The individual pays not merely for mechanization, but for any advance in social organization. "In the hive," says Maeterlinck, speaking of the most perfectly organized society of which we have knowledge, "the individual is nothing, possesses only a conditional existence. His whole life is a total sacrifice to the innumerable and everlasting being of which he forms a part." Human society has not yet risen to those heights of organized perfection attained by the bees; but it is rising. Modern mechanized society is probably man's nearest approach to the hive. Hence the price paid by the individual for the existing social order is higher than the price paid by the individual for any social order of the past. Mr. Babbitt sacrifices more to his Community at Zenith than the Hindu sacrifices to his caste. For if the machine brings many gifts to its slaves, it also demands of them unprecedented sacrifices. "The morality of the machine," says M. Seche, "is the most imperious of moralities, because it is more than a merely materialistic morality; it is a mathematical morality, a morality of cogs and wheels, of driving belts and cranks and moving pistons, a morality subjected automatically to the will to power of organized mechanical force. You do not argue with a machine; either you don't set it going; or else, if you have set it going, you must submit yourself to its rhythm and accept all the consequences." Once started the machine demands (under threat of economic ruin) that it shall never be unnecessarily stopped, never thrown out of its stride. Production and yet more production—that is the fundamental law of the machine's being.

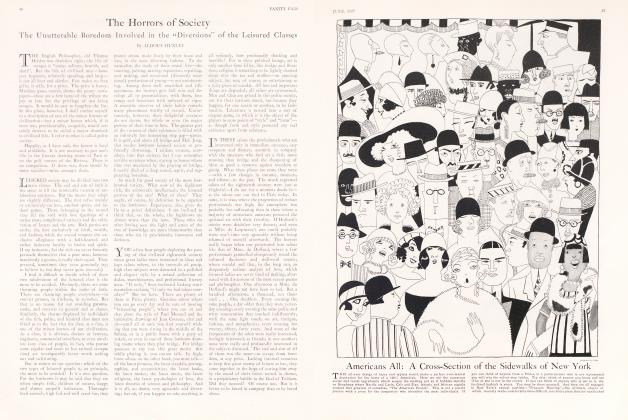

The necessary corollary to this law is consumption and yet more consumption. But this production is a production according to a changeless formula fixed by the machine. The members of a mechanized society may not choose how they shall produce nor what they shall consume. The machine murders phantasy and suppresses personal idiosyncrasies. Its slaves must work in the way (the, for most, modern workers, senseless, monotonous and imbecile way) which it finds suitable to its mechanical needs; they must consume the standardized objects it has created. An enormous propaganda is ceaselessly proclaiming the rightness and beauty of this hideous state of things. With the result that those who are not actively engaged in helping the machine to produce things and eliminate persons are looked on disapprovingly. "The modern man," says M. Seche, "does not work for himself, does not live for himself; he works for society," (the mechanized society whose watchword is production) "he lives to insure the movement, the equilibrium, the activity and prosperity of the national, the human community. . . The community-sense has penetrated us to such a point that a young and healthy individual leading a life of leisure seems to us abnormal, even immoral. . . Obscurely, we feel that he is depriving the community of a force." The two characteristic gospels of modern times—the gospel of work and the gospel of social service—have been imposed on us by the machine. They would be excellent gospels, if the words 'work' and 'service' were broadly enough interpreted; but, in this machine-ridden age, 'work' means economically productive work and 'service' is service of an immediately and obviously useful kind. And yet the healthy young individuals who, in ancient Athens, in mediaeval Italy, in old Japan, were idle gracefully and with refinement, rendered enormous services to qualitative civilization. And the drunken and disreputable Villon, young Teresa in her cloister, old Socrates the professional conversationalist, were quite as genuinely world's workers as Mr. Ford. This, however, the machine cannot admit.

"The law of the machine," to quote M. Seche once more, "is not based on rights, it is based on a categorical imperative. It cannot put up with disobedience. Does the machine tolerate that a crank or a piston should not work? It is equally intolerable to it that the activity of the individual should be exercised outside the order of its morality." And again. "The machine is at the service of the community, not of the individual, however much of a genius. By standardizing work, by making international economic co-operation possible, even indispensable, the machine has acclimatized in us the community-sense." By turning necessities into consoling and uplifting virtues, men have transformed the iron laws of the machine into ideals of service and work for work's sake. But under the verbal tinsel the iron is always iron. There is even (pathetic and touching humanity!) a tendency to exult in slavery to the machine. "Through the community," says M. Seche, "the individual tastes power. ... He disdains a liberty which left the individual impotent in his isolation." And our author goes on to affirm that "the honour of the individual consists in the very fact of his slavery. His honour is in the sacrifice which he makes to the community—a sacrifice imposed by the machine, degrading in so far as the individual seeks to rebel (his defeat reducing him to the state of a conquered foe), but glorious if it is accepted, the individual abdicating his egoism for the benefit of the community."

(Continued on page 158)

(Continued, from page 62)

Social service, as we have seen, is the title of nobility bestowed on our forced submission to the machine and its anti-individualist ethic. The machine demands that we shall sacrifice our individualities; we obey, because we must, but save our face by pretending to do so voluntarily and as a point of honour. And, obviously, what we choose to call our honour is our honour. But the fact that, at a given moment, a certain action is defined as honourable does not guarantee us against that action being, in an absolute sense, harmful. In obeying the ethic of the machine, we are acting, according to our modern lights, honourably. But are we not at the same time acting suicidally to ourselves as human beings? My own opinion (and it is one which many people share) is that we are. Human nature is not indefinitely plastic. The evolution of man took place in a world in which there were no machines; in most of the more important activities of life men have always been free, even under the, politically, most tyrannous regimes, to act as purposive, creative individuals. The invention of this machine has suddenly changed all this. Under the new dispensation men are called upon to make a sacrifice of their creative individualities; and the more perfect becomes the organization of mechanized society, the more complete will be the sacrifice demanded. Making a virtue of our necessities, we may cheerfully immolate our creative faculties, our sense of purposive effort, our idiosyncrasies, our right of aesthetic choice; we may do this and call the process an act of honour. But honour, as Falstaff so justly remarked, cannot set a broken leg and has no skill in surgery. Men have evolved for thousands of generations in a world in which it was not necessary to make such sacrifices as those now demanded by the machine. Our nature is adapted to this unmechanized world. Can we exist under the new conditions without in the long run becoming either imbecile, or else criminally or suicidally insane?

"Everything that serves the individual," pronounces M. Seche, "that raises the level of the human type, that contributes to the permanence of the species, is moral; everything that harms the individual, lowers the level of the human type and threatens the duration of the species, is immoral." An excellent definition, which I accept without qualification. But when M. Seche goes on to affirm that the ethic of the machine is moral, as morality is thus defined, I cannot possibly agree. Is monotonous slavery to a machine of service to the living individual? Is the level of the human type raised by preventing men and women from using their creative faculties, whether at work or at play? Is a species whose members are compelled to sacrifice some of their profoundest and (by all hitherto accepted standards) noblest instincts, likely to survive long? The answer to all these questions is surely an emphatic no. The ethic of the machine is a profoundly immoral, because a profoundly harmful ethic, subversive of the very foundations of human nature.

Is it possible for us to enjoy the benefits of mechanization, while preserving the advantages enjoyed by those who live in a pre-mechanical environment? I do not know; but on the answer to that question depends, it seems to me, the future of our civilization. If it can be answered in the affirmative, we are saved. If, as at present seems somewhat more likely, it can never be answered except in the negative, we are lost. One hopes for the best, but hopes without much conviction.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now