Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Star-Spangled Nichols

Being a Parody Interview by Beverley Himself, in His Most Autobiographical Manner

JOHN RIDDELL

EDITOR'S NOTE: Although Mr. Beverley ("Buffalo") Nichols has earned a considerable reputation among the Women's Clubs of America by writing a series of interviews with our prominent citizens, in which the subject of each interview &as invariably a little less prominent than Beverley himself, Vanity Fair has felt that his list would not be complete unless it included an interview with our own Staff Interviewer, Mr. John Riddell. As a result of this meeting, Mr. Nichols has brought his autobiographical style to its summit of perfection by writing the accompanying interview in which the subject of the interview does not appear at all. The only possible improvement remaining for Mr. Nichols, hereafter, would be to omit the interview as well—a method which we recommend without hesitation

THE telephone rang in the hall of a tiny apartment whose only claim to fame is the fact that I live in it. Down the wire drifted the voice of John Riddell.

"This is John Riddell speaking."

"Yes?"

"You know who I am, of course?"

"Well ..."

"I am the subject of this article by Beverley Nichols."

"There is only one subject of an article by Beverley Nichols," I said, "and that is Beverley Nichols."

"But this is supposed to be an interview with John Riddell," he complained, pointing to the title.

"My dear fellow," I smiled, "when you have been interviewing people as long as I have, you will realize that an interview is only an excuse to talk about yourself. I have been talking about myself now for seven volumes, and I may say I have never tired of my subject. In fact, as I pause and read again the scintillating words I have written—"

"I am coming over to your apartment, directly after crumpets," interrupted John Riddell hotly. "I demand that Mr. Nichols let me into my own interview."

"I am very sorry," I said, "but Mr. Nichols is very busy and cannot be disturbed."

"What is he doing?"

"As a matter of fact," modestly, "he is interviewing me."

"Who are you?"

"I am Beverley Nichols," I said simply. Whereupon he decided not to wait for crumpets.

AND as I pause, and read again that rather scintillating conversation which I have just written, it occurs to me that I catch in my dialogue a mordant brilliance and a flashing rapier-play of wit which, it seems to me, is utterly unexcelled in modern literature. Surely no one has ever written prose which satisfied me so completely. Surely there is only one person who can, in my own estimation, compare with me. I am, after all, unique.

Yet seated opposite me at this moment was the most brilliant young man I have ever met in my life. I gazed at him a trifle enviously. He represented so perfectly all that I wished to be. He was the epitome of intelligence, the acme of wit, the mirror of fashion, the climax of perception, tact and taste. From his pale lavender eyes to the tips of his fawn-tinted spats there was nothing about him which I did not admire with all my heart. At last I was face-to-face with my ideal.

A curious problem is presented to the person who finds himself face-to-face with his ideal. Does he, for example, think you are the most brilliant young man he has ever met in his life? Are you the epitome of intelligence, the acme of wit, the mirror of fashion, the climax of perception, tact and taste? From your pale lavender eyes to the tips of your fawn-tinted spats, is there anything about you which he does not admire with all his heart? Incidentally, isn't it clever the way I have simply repeated the preceding rather scintillating paragraph word for word? Do you mind if I pause and read it over again to myself?

I joined my finger-tips together and studied the young man before me with increasing admiration. He joined his finger-tips together and studied me. I looked him straight in his pale lavender eyes. He looked me straight in my pale lavender eyes. I winked. He winked. There seemed to be a perfect sympathy between us. I crossed my left leg. He crossed his right leg. I took out my watch and wound it. He took out his watch and wound it. We were getting along famously together. I pulled out my bow-tie and let it run back with a snap. He pulled out his bow-tie and let it run back with a snap. I pulled my lips apart, pressed my nose flat with my thumb like a Chinaman, and wiggled my ears. He pulled his lips apart, pressed his nose flat with his thumb like a Chinaman, and wiggled his ears. I hung my knees over the back of the chair (this will stunt him), rested on the bottom rung on one elbow with the chin in the palm of the hand and the forefinger along the cheek, balanced a lead-pencil on my nose, and whistled the first four bars of Turkey in the Straw. He hung his knees over the back of the chair and rested on the bottom rung on one elbow with the chin in the palm of the hand of the forefinger of the cheek of the lead-pencil of the nose of the House that Jack Built . . .

And as I pause, and read again that rather scintillating paragraph which I have just written, it occurs to me that if I pause and reread many more scintillating paragraphs, I won't be getting ahead very fast with this interview.

I gazed at him curiously. (He gazed at me curiously.) What was his position in society? Had his unnaturally sensitive nostrils sniffed out day by day the correct Lists in which his name should be included? Had he proposed himself for all the Clubs That Matter? Had the Best People invited him to their receptions, on his own invitation? Had he ever attended the Albert Hall Ball in a box which contained, in addition to himself, such comparatively minor figures as the Prince of Wales, Thelma Morgan Converse, the Archbishop of Canterbury, Sir Philip Sassoon, the Emir of Afghanistan, Countess Folke-Bernadotte, Mr. James Hazen Hyde (twice), Havelock Ellis, Mme. Dubonnet, and Mrs. Cornelius Vanderbilt?

HAD he, for example, ever interviewed Lindbergh? Poor "Lindy"; a rather good aviator, as I recall, but I shall never forget the wistful appeal in his eyes as he gripped my hand and said: "Ah, Nichols, if you would only teach me to fly!"

Had he interviewed Henry Ford? Did he remember, as I did, the look of mingled admiration and envy which crossed the face of that rather efficient automobile manufacturer when he was introduced to me? "So this is Beverley Nichols," he said. "I've always wanted to meet Beverley Nichols. Nay, more —I've always wanted to be Beverley Nichols. If I had your brains," he sighed, "I'd be a wealthy man today."

Had he known Charlie Chaplin? Had he, too, seen beneath the tinsel a heart of gold? (Had he, for that matter, ever been able to toss off a neat figure of speech like that, practically with the back of his hand?) And had he heard the break in the voice of that rather amusing motion-picture actor as he said to me: "I try to be the funniest man in America, Beverley—but you are the funniest man in America."

Had he heard Jack Dempsey whisper to him, in the shy manner which is characteristic of that rather adequate pugilist: "Say, Nick, sometime show me how to box. Huh?"

Had Calvin Coolidge, the rather retiring President of the United States, sighed to him over the breakfast table: "Beverley, I'd give up my choice to run in 1982 if you would only consent to become an American citizen."

Was he sufficiently impressed by all these names? Was he properly overwhelmed by such a list of rather important people whom I had done the honour of interviewing? I studied his face carefully. Our glances met. There was no more sign of astonishment in his eyes than there was in my own.

Continued on page 110

Continued from page 73

So that was his game! Well, my proud fellow, two can play at that as well as one. If he desired to simulate boredom and pretend an indifference to the overwhelming charms of my magnetic personality, I could do as much toward his. So far I had made all the advances in this interview; he had not even said a word. Now let him make a few attempts to impress me. In the meantime I could sit back and snub him, snub for snub.

I yawned. He yawned. Very good, my bucko! My head nodded forward. His head nodded forward. Oh, it did, did it! I shaded my eyes with my hand. He shaded his eyes. There was a loaded silence.

Come, my fine fellow! A little of this is enough. Beverley Nichols has never been treated this way in his life. I peeked cautiously through the fingers of my hand, just in time to catch him peeking cautiously through the fingers of his hand.

I glanced up quickly. He glanced up quickly. We glared at each other. I half rose. He half rose. I shook my fist. He shook his fist. "You cad!", we shouted simultaneously.

With a choked cry of rage I reached for a book, and hurled it forward at him with all my might. There was a terrific crash, a splintering of glass, and a dull thud . . .

The young man before me had vanished.

I had vanished.

There was a repeated knocking at the door of the tiny apartment whose only claim to fame is the fact that Beverley Nichols lived in it. Through the keyhole drifted the voice of John Riddell.

"Let me in."

No answer.

"Let me into this article at once," he repeated in a louder voice, "or I shall break down this door."

With a heave of his shoulder he threw' his weight against the delicate oak panels. The door splintered, and fell in with a crash. John Riddell sprawled forward into the room, regained his balance, and then gazed about him with increasing bewilderment.

The room was utterly empty. In the center of the floor stood a vacant chair. Before it were the shattered remains of a full-length mirror, the jagged bits of pane still clinging to the frame. And on the floor, amid the debris of broken glass, lay a book.

John Riddell picked up the volume from the floor, glanced at the title*, and shook his head sadly.

♦THE STAR-SPANGLED MANNER, by Beverley Nichols (Doubleday, Doran).

1927—1928

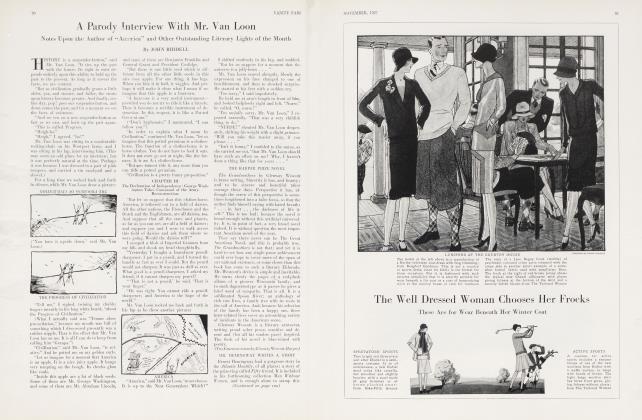

As this year of belles lettres winds to its conclusion, (this is being written way back in December, and it Drobablv looks nrettv silly now, what with all the violets in bloom) most of my fellow-reviewers are entertaining themselves with arbitrary selections of the Ten Best Books of the Year, which they offer to their awed readers on tablets of enduring bronze with crossed laurels and a small critical standard fluttering overhead in the breeze of. an electric fan.

Myself, I entertain no such illusions. I have no idea what are the Best Books of 1928. I have no idea how to tell when a book is a Best Book. Probably I haven't read more than five of the Ten Best Books, anyway. Probably, for that matter, at least one or two of them have never been published in the first place.

No. I have just one standard in reporting on a book (now that we are being cozy and fratty together, and please not so much ginger ale with mine next time) and that is whether or not I like it. Therefore, if I am to be of any real service to a reader, he should know the sort of thing I am apt to like; and if his standard of taste happens to be similar to my standard of taste, then it stands to reason he will enjoy the books I recommend. This is a rather fundamental axiom of all criticism, and it is nothing new at all; but in these days of pontifical pronouncements at nine dollars a newspaper column, it is sometimes lost sight of. In the immortal words of Henry Beston, "99 of American criticism is either heckling or opinionated ploop."

Looking back over the' year, from December 1927 to December 1928, I find that I recall a certain number of books with distinct pleasure. They are books I really enjoyed. I don't know how many there are: fourteen or fifteen, and of course there will be one or two others that I shall remember just after this copy has gone to press. But I am setting them down here at random, not in any sense to offer a list of Best Books, but rather to express my sincere indebtedness to these few authors for several hours of very real enjoyment:

"ELIZABETH AND ESSEX," by Lytton Strachey (Iiarcourt, Brace).

"THE OUTERMOST HOUSE," by Henry Beston (Doubleday, Doran).

"ETCHED IN MOONLIGHT," by James Stephens (Knopf).

"THE SET UP" by Joseph Moncure March (Covici, Friede).

"COWBOY," by Ross Santee (Cosmopolitan).

"A VARIETY OF THINGS," by Max Beerbohm (Knopf).

"THE CASE OF SERGEANT GRISCHA," by Arnold Zweig (Viking).

"SQUAD," by James M. Wharton (Cotvard-McCann).

"CONDEMNED TO DEVIL'S ISLAND," by Blair Niles (Harcourt, Brace).

"POINT COUNTER POINT," by Aldous Huxley(Doubleday, Doran).

"SUNSET GUN," by Dorothy Parker (Liveright).

"INNOCENT BYSTANDING," by Frank Sullivan (Liveright).

"ORLANDO," by Virginia Woolf (Harcourt, Brace).

"MEANING NO OFFENSE," by John Riddell (John Day).

Which shows you just about the kind of taste that I have.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now