Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Business Stroke

An Advocate of Prosaic Simplicity Makes Some Derogatory Remarks on Poetic Methods in Golf

BERNARD DARWIN

I turning lazily over the pages of a Sporting Magazine I have just lighted by chance on a photograph of the illustrious J. H. Taylor at the finish of his swing. It is a thoroughly typical finish with the right foot almost fiat on the ground (there is just a suspicion of daylight visible under the heel), both elbows quite close to the body and the hands well below the left shoulder. I have no manner of doubt that the stroke was equally typical—as straight as an arrow, bisecting the fairway.

The picture is entitled "A business teeshot." I do not positively know who gave that title, but I can make a very good guess. It was an old friend of mine, an admirable writer both on golf and cricket, and I know also whence he took that title; it was from a favourite story of his own. This story concerns Wilfred Rhodes, a very great cricketer, who is still playing for his native Yorkshire at the age of or, and is a thoroughly dour, shrewd, fighter, such as that hard-headed county breeds. A party of whom he was one, were discussing the cut which is perhaps the most flashing, dashing, entrancing and perilous strokes in all cricket. Rhodes listened to those who rhapsodised and then doggedly remarked ''Say what you like it's not a business stroke."

Here is an admirable and pregnant phrase and it could not be more appositely applied than to that firm, steady, perfectly balanced, compact style of Taylor's, which seems as far as is humanly possible to have disclaimed all superfluous and meretricious ornament and left the smallest possible loop-bole for inaccuracy.

TYLOR himself is a romantic creature with something in him of the poet. No man, amateur or professional, is more conscious of the nameless thrill and magic of golf than he is, but he has never let his poetical nature interfere with his strictly business-like method of hitting the ball. lie has always aimed at simplicity and accuracy in striking as being the most profitable; he has never for a moment allowed himself to go worshipping after the strange gods of length or "fancy" shots. "Business first, pleasure afterwards" might have been bis motto, and there is a touch of it in the various aphorisms which he has given to the golfing world. "What's the matter with the middle of the course?" is his answer to those who talk too learnedly about intentional slices and hooks. "Flat-footed golf, sir, flat-footed golf every time" is his simple slogan as regards foot work, and to those who praise the running up shot he declares that "there are no hazards in the air." Perhaps incidentally, he carried that doctrine in a single instance too far, as when he pitched boldly to the famous seventeenth green at St. Andrews, with that cruel, hard, road immediately behind it; but that "is another story."

At a time when there was much praise for players who had what was called "variety of stroke Taylor appeared on tin* scenes playing, as it seemed, all the shots in much the same way. When everybody had a long swing be had a short one. When a tremendous follow-through was considered an essential part of orthodoxy, he seemed, though here was something of an optical illusion, not to follow through at all. He is still playing magnificently when nearing sixty, and he has seen the world very largely converted to his "business-like" views of the best way of hitting a golf ball. I do not say that he did the converting, only that he was one of the first to act on principles now generally recognized.

Taylor was a golfer with no frills anti to-day a great many frills that were once considered essential virtues have now been cut out as vices. I will not repeat all over again what I said the other day in writing about "standardized" golf; enough to say briefly that once upon a time it was thought the height of wickedness to swing an iron club in the same manner as a wooden one, or indeed to swing it, in a technical sense, at all; it was further thought that there were several perfectly distinct varieties of iron shots, each of which demanded something different in the method of playing it. To-dav it is rather held that there is one correct method of swinging a golf club, and that the only difference need be in the particular club which is swung to meet the particular case.

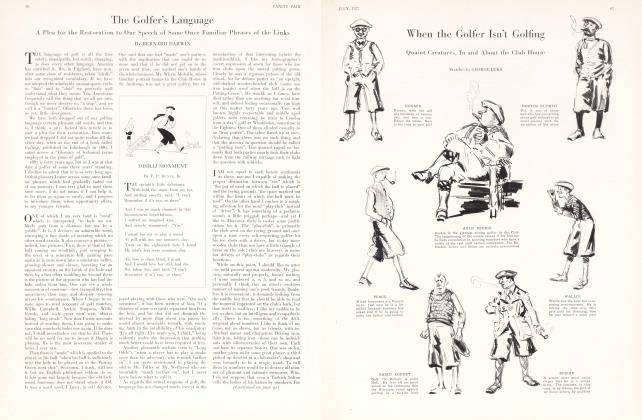

Let me give some other instances of this strict attention to business in placing golf to-day. Take what is still called the "waggle." This is in the case of the modern golfer nearly a courtesy title. It is said of the famous 'A oung Tommy" Morris that he "used to waggle his driver with such power and vehemence in his vigorous young wrists as often to snap off the shaft of the club close under his hand, before ever he began to swing proper at all." Shafts no doubt were frailer in his time than in ours, but can one conceive a champion of to-day snapping thus the feeblest of shafts? Take a much more modern example. Some of my readers may remember the late Mr. Norman Hunter (lit' was killed in the War) who was a member of the Oxford and Cambridge Society team in America long ago and later played in the Championship at Wheaton in 1912. Anybody who ever saw "Norrie" play will recall tbe joyful ferocity of bis waggle in which not only his club but the whole of his anatomy seemed to be hurling menaces at the ball and tbe foe. Such a waggle as his, a little exuberant in his own time, is now extinct. Almost the last place you would find it is in its original home, Scotland, where the young players have all cultivated a deliberate tranquillity of address towards the ball.

THE old text-books used to discover various more or less convincing reasons for doing what everybody did, i.c. waggle. Some authors said it was to loosen the wrists, others that it assisted a shuffling process of the feet whereby the right distance from the hall was gauged; the great Sir Walter Simpson said its object was "to let tbe hands settle to their grip." In course of time there came along young iconoclasts who examined these pronouncements with sceptical eyes declaring that after the first stroke or two their wrists did not feel stiff, and that they could perfectly well place their feet and grip their did) without all those flourishes. Moreover, it is at least a reasonably sound maxim that as you waggle so you swing. If in your preliminary flourishes you rise and fall like the waves of the sea, bend your knees too freely and burl your weight now onto this foot and now onto that, you are likely to do some of the same things in your swing. And so the new generation have cut down the waggle to one or two little restrained pieces of aiming at the ball.

An old dog cannot learn new tricks, and to one brought up in the more flamboyant school it seems that something more than this embryonic waggle is needed to get up sufficient steam for the swing. The new players can do it, however, and put more steam into their hitting than ever the old ones did. The old free waggle is not wholly dead yet amongst our amateurs. Cyril Tolley's style, which to my eyes is a glorious one, still has some traces of it, but when I summon up mental pictures of the great American amateurs they all seem to me to be addressing the ball like Bohhy Jones, who hardly addresses it at all.

Continued on page 122

Continued from page 81

Turn to the putting green and we see that certain rather attractive but probably also destructive mannerisms have almost disappeared. Some forty years ago Mr. Horace Hutchinson wrote that "most of the professionals give a curious little knuckle inward of the right knee, just before they draw the club away from the ball" and went on to suggest that it was possibly "a survival of the dashing style of poor Young Tommy." I am old enough to remember the time when practically all the Scottish professionals and professionally moulded amateurs had that curious knuckling movement, and I and other imitative little boys of my age used positively to knuckle and ripple all over our small frames in pious imitation. You very seldom see that to-day. The putter now stands as still as ever he can whether in addressing or striking. Sometimes he suffers from excessive zeal. The good putter, though he stands essentially still, yet has some little almost imperceptible movement, which gives the rhythmical quality to his stroke.

In the actual method of hitting the ball what I have called business principles prevail. Yet in another direction golf has grown infinitely more dashing than ever it was. How seldom do we see or hear now of a great player "playing for safety." The phrase is hardly used at all. The man who wins championships is going out for everything all the time; he must and does take risks that would once have been deemed foolhardy. "Take your cleek for safety" was once a piece of advice given even to very good golfers when they were actually within reach of the green with a wooden club. A man who does not habitually go for the green when he is within reach of it would soon be left behind nowadays. I began this article with J. H. Taylor, and it is always said that it w'as he more than any other one man who did away with safety play by lashing lull brassey shots up to the Prestwick greens on his first appearance in a Championship in 1893. Certainly there was something in the way in which he played a wooden club shot to the pin, just as if it were a mashie shot, that seemed unlike anything one had ever seen. I have by a lucky chance, had the pleasure of a day's golf with him. He takes wooden clubs nowadays when the lusty young men take irons, but once within reach the ball still goes straight to the green. At one tee—to a long one-shot hole -the great man debated aloud and with explanatory gestures whether he should hold the ball up into the wind with a hook, or let it drift in a little from the left. All I saw was the ball making a bee line for the flag.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now