Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThree Legends

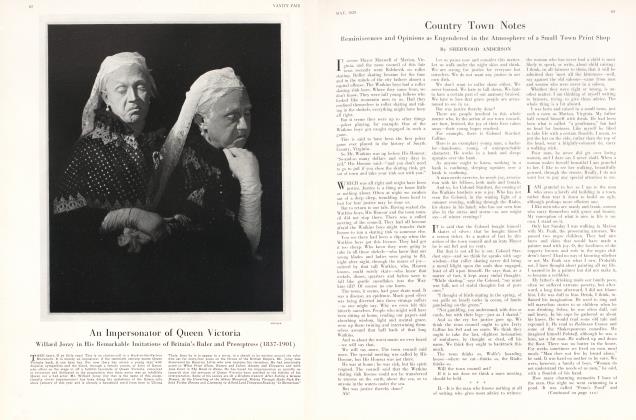

Wherein an Employee, a Husband and a Restaurateur, Are Subjected to Embarrassment

FERENC MOLNAR

§i

SCENE: the corner of a cafe frequented by artists. (They always arrive in the late afternoon, a few minutes after dusk. Their table is the noisiest of all. They talk with much gusto and temperament, several of them at the same time. I am convinced that the reason for their strange behaviour may be found in the fact that painters do not stop working when they want to, but when sunset compels them to do so. Consequently, the artist, still full of inspiration, cannot possibly put brakes on his excited nerves from one minute to another. He hurries to his cafe, to his colleagues, and there he continues to paint pictures, word pictures until he gets tired of it.)

As I was saying, the painters' table. But— this time they are not talking of art. Their arguments are as old as humanity itself. "He is a bad man!" "He isn't really bad. He is only an egotist!" Then: a vehement discussion about the difference between the good man and the bad man. Very feeble examples of an occasional good man. Brilliant examples of bad men. Finally: a contest. Who committed the greatest, most perfect mischief? Prize: a big cigar. I shall relate here only the prize-winning mischief.

"I WAS sixteen years old," begins one of them, "and, with my schoolmates, we gave a New Year's Eve party. It was about eight o'clock in the morning when we started to go home in the snow. We drank a great deal and were all recklessly good-humoured. Passing by a letter-box I noticed that the corner of a letter peeked out from the slit through which one drops letters into the box. The box was full of belated New Year's greetings and there was no room for some of the letters. I took the envelope out of the box. As we all know, some people do not seal letters because postage rates are smaller when they are unsealed. There was a namecard in the envelope, the card of some Second Assistant Manager in one of the government offices. The text wished the honourable Mr. So-and-So a very happy and prosperous New Year. Mr. So-and-So's name and title were on the envelope and we observed that Mr. So-and-So was the Second Assistant Manager's immediate superior.

"'Come,' I told my friends. 'This will be a great joke.'

"We went to the next cafe and asked for pen and ink. I was fairly adept in imitating anybody's handwriting so I took the pen and, after a few attempts on a piece of paper, changed the period at the end of the Second Assistant Manager's sentence to a comma and added the following to it: 'and takes the liberty to warn him that if he continues to treat his inferiors in the same stupid and unjust manner in the New Year as he did in the past, he will soon come to grief.'

"The forgery was perfect. I put the card back into its envelope, dropped the envelope in the letter-box, laughed, and went home to sleep. That's all."

The jury adjudged him the prize on the following grounds:

1. The mischief done was totally unselfish.

2. The consequences of the mischief were well-nigh infinite. Consider the chief's first surprise when he received the card. Or, the first meeting between the chief and his wellwisher. Did the chief tell him anything about it or did he merely let him feel the power of his anger throughout the remainder of his official life? What did the well-wisher say when the chief actually showed him the card? Did the chief believe the well-wisher when he swore that he had not written the second half of the sentence? Who else had written it? Who else could have possibly written it? Then the well-wisher's sleepless nights during which he tried to figure out this infernal puzzle for himself. How did the new lines get into the letter? The chief's thoughts: had this man gone crazy? Or, supposing that he did believe that someone else had written the second part, who was interested in the insult? Had the forgery occurred in the well-wisher's or in the chief's house? Or perhaps there was no forgery at all, the well-wisher merely made a bet that he would "tell the boss where to get off."

Then the possible psychological effects of the affair on the chief: did he actually begin to contemplate whether he had treated his inferiors in a stupid and unjust manner or did he not? The two men must have thought of a thousand possibilities, but never once of the true one: namely, that a perfect stranger had taken the card out of the mailbox, hastily added a few words to it, and had then thrown it back again.

§2

CENE: the terrace of the cafe of a grand hotel de luxe, the most expensive of them all, at Carlsbad, at the height of the season, in Summer. Time: three o'clock in the afternoon.

The terrace is crowded to overflowing. The windows of the rooms on the second floor are directly above it. Suddenly, a lady appears in the window on the corner and calls out to her husband who is quietly sipping his after-lunch coffee on the crowded terrace:

"Leo, I want to read the paper and I can't find it. Where have you put it?"

All the patrons on the terrace crane their necks in the general direction of the pretty woman in the window.

"I think it's on the night-table," answers, somewhat embarrassed, Leo.

The woman disappears from the window. Leo is visibly annoyed because of the attention she has created. A second later, she appears again, but this time in the window next to the corner-window.

"It isn't there."

"Then I don't know where I've put it," answers Leo.

The woman disappears from the second window, only to reappear a moment later in the third one:

"Haven't you taken it with you?"

"No, I haven't."

She withdraws from the third window and reappears in the fourth one:

"Isn't it in your pocket?"

"No, it isn't."

She retreats from the fourth window and shows herself in a fifth one:

"I can't find it anywhere."

Leo is utterly embarrassed, for every time his wife comes into view, the attention of the entire terrace is aroused and everybody looks up at her. He is already blushing.

"Just look for it," he says.

She disappears again, but soon she springs up in the sixth window, then in the seventh, and, finally, in the eighth one, reporting every time that she cannot find the newspaper.

Leo is a good husband. He rises, goes to the newsstand in the lobby, buys the paper, and takes it up to his wife. When he enters the room, his wife is sitting in an armchair reading the paper.

"What's this? Have you found it?"

"I have never even lost it," says she.

The answer renders Leo speechless.

"What are you staring at me for?" asks she. "We've been here only since this morning and I simply had to find a way to let the hoi polloi know that we occupy a four room apartment on the second floor which has eight windows."

§3

HE late Wampetics told me this story on a Summer's day, at lunch, beneath the shadowy trees of the garden of his restaurant, dear old Wampetics, dean of Budapest's restaurateurs. I remember it, because it had a Biedermeyer flavour and because it characterized a refined and tactful old gentleman. This refined and tactful old gentleman was Baron Frederick Podmaniczky, exspeaker of the Hungarian House of Representatives who ate his lunch, day after day, year after year, from early Spring until late Autumn, in complete solitude at his accustomed and regular table in Wampetics's garden.

Wampetics's was an amazing place: superb cuisine, much clatter, overwhelming temperament. One day, they took the soup to Baron Podmaniczky and there were two flies in it. And this was not the first time.

The Baron put down his spoon and called the waiter:

"I should like to speak to Wampetics."

Wampetics arrived breathlessly and bowed deeply:

"My dear M. Wampetics," began Baron Podmaniczky in a gentle, charming, barely audible voice, "it is very praiseworthy of you to try and please me at all costs, but who told you that I like my soup with two flies in it? Now, if you want to do me a really great favour, please, be kind enough to give me my soup clear, and serve the flies on a separate plate.

I shall then put just so many of them in my soup as I fancy most at the moment."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now