Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowA Carefree Cartoonist

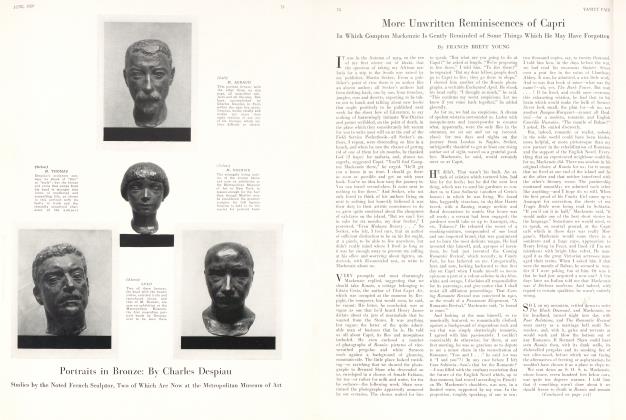

H. T. WEBSTER

A Member of a Noble Craft Unlooses His Repressions and Makes the Reader Grouch-Conscious

I AM aware, as I begin, that this article is foredoomed to vanish into the abyss of a Popular Preconception. Writing it is an entirely futile exercise. I think I may lay claim to being an authority on the craft of being a practising cartoonist, and yet what I have to say on the subject will carry less weight for my readers than a Democratic vote in Philadelphia. All my tears and protestations will not stir one heart.

"Oh, the joker!" people will say and continue to believe that drawing cartoons is the easiest and most delightful way of passing the time in the entire curriculum of play-boy pastimes.

I have read a good many articles by cartoonists and I cannot remember one that did not advertise the grinding labour involved in supplying a newspaper with a daily drawing. Nearly every cartoonist I know admits that he would prefer ditch-digging, driving a truck, being President of the United States, or almost anything along those lines that offered leisure and mental relaxation.

But the layman who is invariably somewhere on the fringe of the gathering merely smiles in that what - droll - fellows -these-cartoonists-are manner and says that he wishes Fate had cast him as a cartoonist, golf Pro or something where work wasn't a factor.

THE story of the Hindu fakir who tosses a rope into the air, up which a boy climbs until he disappears, is accepted by practically every non-resident of India, including those who do not read the tabloids; it has become an invulnerable tradition. And yet this venerable fiction has been exposed again and again. We continue to believe. The lie is immortal. This ancient item in the public's mental baggage is exactly analogous to the legend of the easy, carefree life of the cartoonist. That lie, too, is so firmly entrenched that it promises to be immortal. Nothing I can say will dislodge it. Therefore, the utmost that I expect to accomplish is to unload a number of grouches that have been festering in my system all these inarticulate years. My aim shall be to make the reader grouch-conscious.

I have been drawing cartoons for twentyseven years. During that period I have produced an average of more than six cartoons a week. This probably will not impress anyone else but it does me. 8,424 cartoons make a lot of cartoons and I don't care what anyone says. It is a temptation to resort to the old device of laying these cartoons end to end and figuring how far they would reach, or estimating how many elephants or editors could be

drowned in the India ink I have spread on paper, but I am going to resist. I shall be satisfied if I do no more than make this point: I have drawn enough pictures to give the novelty of it a pronounced deckle-edge. The first fine fury has become decidedly shopworn. From my biased point of view it has been mighty hard work. All this, however, would be better than tolerable but for its corollaries. I am not complaining of the actual labour of filling three columns daily and a page on Sunday but of the conditions indirectly connected with it, but apparently inescapable. To show what a hardy weed the surviving cartoonist must be, I shall list a few of the beetles, slugs, weevils and dry rust that feed on him and annually decimate his ranks.

HARDIN COUNTY-1809

The big winner in a poker game who says, as he cashes in his stack: "I'd like to play the rest of the night but, unfortunately, I have to work for a living. I'm no cartoonist."

The man who slaps me on the back and delivers himself of this dynamite: "Well, I see you're still drawing pictures. I'm going on a vacation MYSELF next week."

The vertebra of his country who asks: "You only draw one picture a day? What else do you do?" And then there are the little darlings at dinner parties who lisp in their cunning, roguish way: "Now, Mr. Webster, don't you put me in a cartoon!", and then the well-meaning soul who tells me how much he liked a certain cartoon of mine, going on to describe it in detail. As the description proceeds I realize that the cartoon was drawn by someone else and the problem arises whether to agree that the cartoon was good or modestly to deprecate it and risk having him learn the truth.

Then there is the man whose opinion I have always respected who lavishes me with praise until I conclude that my appraisal of his character and judgment had been correct and who goes on to say that there are just two cartoonists whose work he watches, myself and so-and-so, naming a man whose work nauseates practically every member of the craft. After that one wonders whether it is all worth while.

THE daily mail is a never-ending source of delight to the cartoonist. Much of it consists of ideas for cartoons, of which about one out of 5,000 is usable. Despite these odds I open every letter expecting to find pay dirt. Of course some of these contributed ideas are really funny, but are eliminated as possible material by pictorial or other requirements. Two suggestions from the versatile Groucho Marx will illustrate. "Make the Timid Soul's brother a professional fighter," writes Groucho. "Show him going to a fight and accidentally being seated in the wrong corner with the seconds and followers of the rival scrapper. The Timid Soul ends by rooting against his brother." Or: "The Timid Soul buys a new car and is warned not to drive faster than 25 miles an hour for the first 500 miles. While creeping along at 12 miles an hour bandits pursue him in another car. He speeds up to 25 miles an hour and holds it until caught and robbed."

No matter how careful we may be with our cartoons it seems impossible to avoid stepping on someone's toes. The result of this is a letter to the editor containing the phrases "this alleged humour," and "I've always read and admired your paper until to-day."

A curious thing I have noticed is that letters of criticism are invariably sent to the editor and the complimentary ones to the cartoonist. I have finally decided that the cranks who write them hope summary and homicidal action will be taken and the cartoonist kicked piece-meal out of the office. The only crank letter I have ever answered (I told him this in my opening paragraph) was from a preacher in the middle west. This man objected to a cartoon in which a Sunday school superintendent figured in a harmless manner. The letter, an unusually vicious one, was sent to the editor of the paper and I know the writer secretly hoped I would be fired and starve to death.

(Continued on page 124)

(Continued from, page 49)

A drawing dealing with oil furnaces calls forth a wail from the coal interests. A facetious treatment of plumbers, motor-cycles, dentists, movieactresses, etc., brings prompt protests from the publicity bureaus representing these various professions and industries. If considerable restraint is employed, it is reasonably safe to use such subjects as the weather, mosquitoes, Congress and the flu.

(Continued on page 132)

(Continued from page 124)

One of the strangest reactions to my work occurred recently. I lambasted the autograph fiends and for a week or so following the publication of the cartoon I was overwhelmed with requests for autographs. And still people go on believing that ridicule is the most powerful weapon of the human mind.

Well-meaning critics and vitriolic letter-writers are not the only troubles that beset a cartoonist. For some reason a newspaper art department is a magnet which attracts loafers, cranks, bores and monstrosities of every description. They swarm into the office every day of the week and they are all very leisurely and deliberate about leaving. Some have been known to bring their lunch.

While I am humped over a drawingboard trying to hatch up an idea, there is usually a visitor with his feet on my desk suggesting that I make a picture calling for a large crowd of men in silk hats and carrying umbrellas or a long procession of automobiles. Their ideas invariably involve things that are difficult to draw.

The next specimen to lavish his attention on me is apt to be the father of a genius. He will sit on the corner of the desk, upsetting the ink bottle, and tell me that his daughter, who will be 14 next September, has taken up art but doesn't draw much better than I do. Where is a good art school that will sort of polish up her work and make it look professional?

From 10:30 on the traffic increases until the peak is reached at 3:05. Insurance agents, book agents, geniuses (with and without their parents or managers), office boys from other departments of the paper, borrowers, promoters, bond salesmen, flocks of school children with a courier and men who just want a comfortable chair in a warm room arrive in such numbers that it is almost necessary to have one-way aisles between our desks and a stagger system.

Among the more picturesque callers who have kept us from becoming too engrossed in our work I recall the rather personable lady who walked in and announced in a loud voice that she was a grandmother and was being sued at the moment for breach of promise. She then passed around to every artist in the room large photographs of herself in the nude. This incident had great entertainment value but was of no practical help in getting out a cartoon for a family newspaper.

Then there was the strange looking unclassifiable who eased himself into the office and announced that he wanted a job as "model for funny faces." "I can make any kind of a face you want," he said, "anger, fear, mirth, surprise, pathos, anything. LOOK!" And he proceeded to demonstrate.

Last fall a young man called. He had not been in the room five minutes before we spotted him for a neckfanner. A neck-fanner, in case you don't know, is the king of art department abominations. His interest in a drawing under construction leads him to bend over the back of the chair and breathe on the artist's neck. It may be an unreasonable prejudice but most of us care very little for neckfanning. Will Johnstone, who draws a news cartoon for the paper, and I were the only ones favoured by this particular visitor's attention. He divided his time equally between us and as his interest increased so also did the breeze on our necks. When our endurance reached the breaking point we began our dialogue. We started mildly. Will asked me if I had heard that Doug Fairbanks, Charlie Chaplin and Jack Dempsey were all upstairs in the local room giving away autographed photographs. We expected our young man to jump over the desk and tear for the door at this. He didn't budge from his post at the back of my chair, so I tossed off something like this for his benefit: "Will, did I ever tell you about the youngster from Newark who was watching me work? He got his nose down on my cartoon and covered with fresh ink. Blood poisoning set in and he died three days later in horrible agony."

There seemed nothing left to do but make our remarks more pointed and strictly personal. We did. Vitriol flowed like water. We watched the boy during this cloud-burst of heavy sarcasm and his face showed the same mobility of expression to be observed on the Public Library lions. Just then someone opened the door, beckoned to the boy and he left. When the laughter subsided we were informed by our colleagues that the unfortunate youngster was deaf and dumb.

Now and then the sun breaks through the clouds. There was an office boy named Wilbur in the Sunday department next door. Wilbur spent nine-tenths of his time in the art department. The other tenth was consumed in being thrown out of the room by the long-suffering artists. The most commendable quality in the boy was his curiosity. He was a talented snoop and nothing of a private nature was safe in his vicinity. One afternoon Wilbur, in rummaging through the Sunday editor's desk, made a find. It was a memo and read, "Don't forget to fire Wilbur to-morrow."

The remainder of the cartoonist's troubles are hardly worth mentioning. There is merely the matter of getting an idea every day in the year and putting it down on paper—trifling mechanical details.

To those readers who want to become cartoonists I shall make so bold as to offer a word of advice. Develop the habit of doing all your work in a cave, preferably inaccessible. Hang a sign over the entrance reading "Leper" or "Unclean". This will at least keep the insurance agents away. If you find that you must mingle with the general herd never let them suspect the profession you follow. The time you will save by following this advice will permit you to get so many years ahead with your work that you can quit in the full bloom of your prime, enjoy the company of your family, and never have to draw another of the loathesome nightmares as long as you live.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now